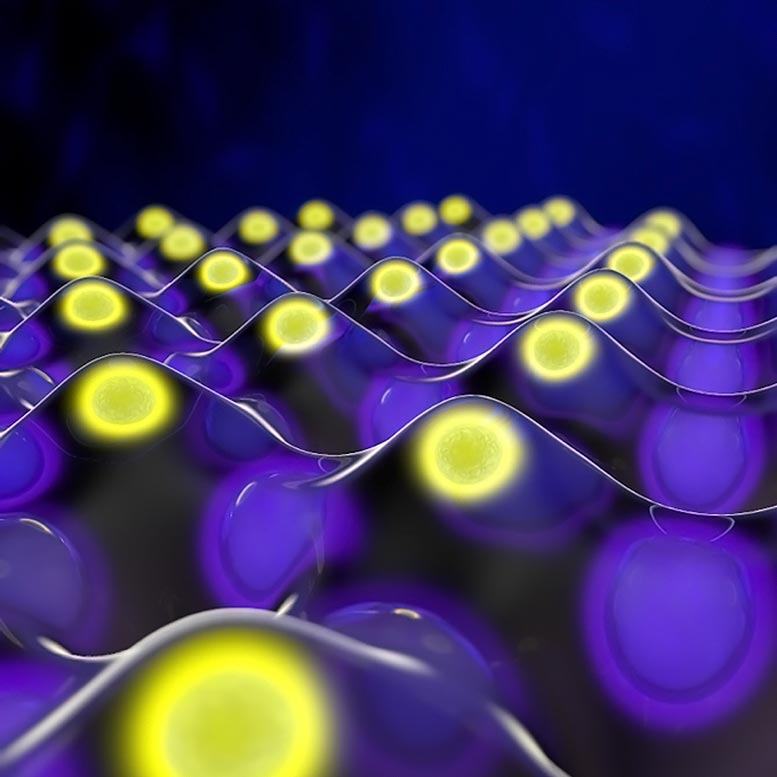

The researchers used powerful laser flashes to irradiate thin, films of crystalline materials. These laser pulses drove crystal electrons into a fast wiggling motion. As the electrons bounced off with the surrounding electrons, they emitted radiation in the extreme ultraviolet part of the spectrum. By analyzing the properties of this radiation, the researchers composed pictures that illustrate how the electron cloud is distributed among atoms in the crystal lattice of solids with a resolution of a few tens of picometers which is a billionth of a millimeter.

The experiments pave the way towards developing a new class of laser-based microscopes that could allow physicists, chemists, and material scientists to peer into the details of the microcosm with unprecedented resolution and to deeply understand and eventually control the chemical and the electronic properties of materials.

For decades scientists have used flashes of laser light to understand the inner workings of the microcosm. Such lasers flashes can now track ultrafast microscopic processes inside solids. Still they cannot spatially resolve electrons, that is, to see how electrons occupy the minute space among atoms in crystals, and how they form the chemical bonds that hold atoms together. The reason is long known. It was discovered by Abbe more than a century back. Visible light can only discern objects commensurable in size to its wavelength which is approximately few hundreds of nanometers. But to see electrons, the microscopes have to increase their magnification power by a few thousand times.

Comments are closed.