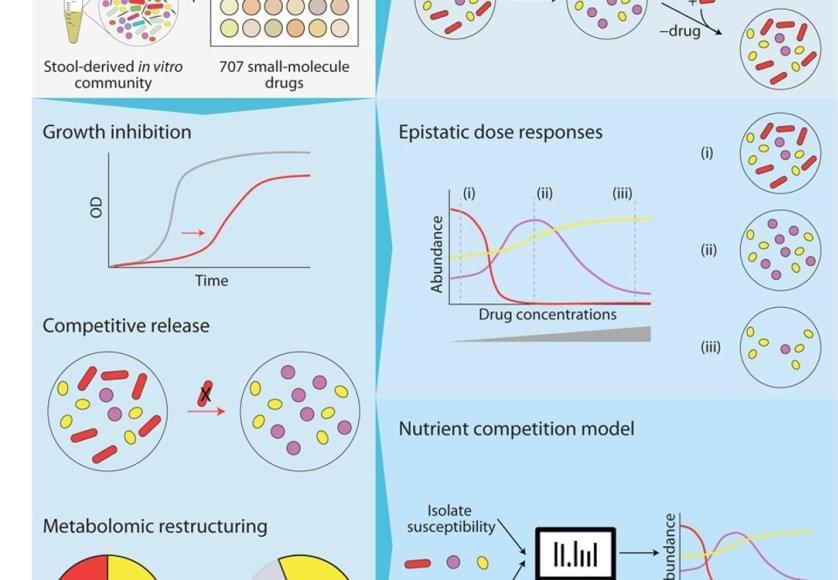

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is closely linked to gut microbiota dysbiosis. We synthesize evidence that carcinogenic microbes promote CRC through chronic inflammation, bacterial genotoxins, and metabolic imbalance, highlighting key pathways involving Fusobacterium nucleatum, pks+Escherichia coli, and enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF). Building on these mechanisms, we propose a minimal diagnostic signature that integrates multi-omics with targeted qPCR, and a pathway–therapy–microbiome matching framework to guide individualized treatment. Probiotics, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), and bacteriophage therapy show promise as adjunctive strategies; however, standardization, safety monitoring, and regulatory readiness remain central hurdles. We advocate a three-step path to clinical implementation—stratified diagnosis, therapy matching, and longitudinal monitoring—supported by spatial multi-omics and AI-driven analytics. This approach aims to operationalize microbiome biology into deployable tools for risk stratification, treatment selection, and surveillance, advancing toward microbiome-informed precision oncology in CRC.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent malignant tumors worldwide. According to the latest data released by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the global incidence of CRC is expected to exceed 3.2 million new cases in 2040, with nearly 1.6 million deaths, ranking third among all cancers after breast and lung cancer (Morgan et al., 2022). While early detection rates are relatively high in some developed countries, such as the United States and European nations, due to well-established screening programs, the situation remains critical in developing regions including India and Africa, where screening coverage is limited and over 60% of cases are diagnosed at advanced stages (Lee and Holmes, 2023). This “high-incidence and high-mortality” pattern not only poses a significant threat to public health but also imposes a considerable burden on global healthcare systems.

With the rapid development of high-throughput sequencing, metagenomics, and metabolomics, the role of the gut microbiota in human health and disease has drawn increasing attention (Fan and Pedersen, 2020). Gut microbes maintain intestinal homeostasis and host immunity. They also contribute to CRC via chronic inflammation, bacterial genotoxins, oxidative stress, and dysregulated microbial metabolites (Dougherty and Jobin, 2023; White and Sears, 2023). Given that the colon and rectum harbor a highly dense microbial ecosystem, gut microbiota dysbiosis is now considered a pivotal environmental factor contributing to CRC onset and progression.