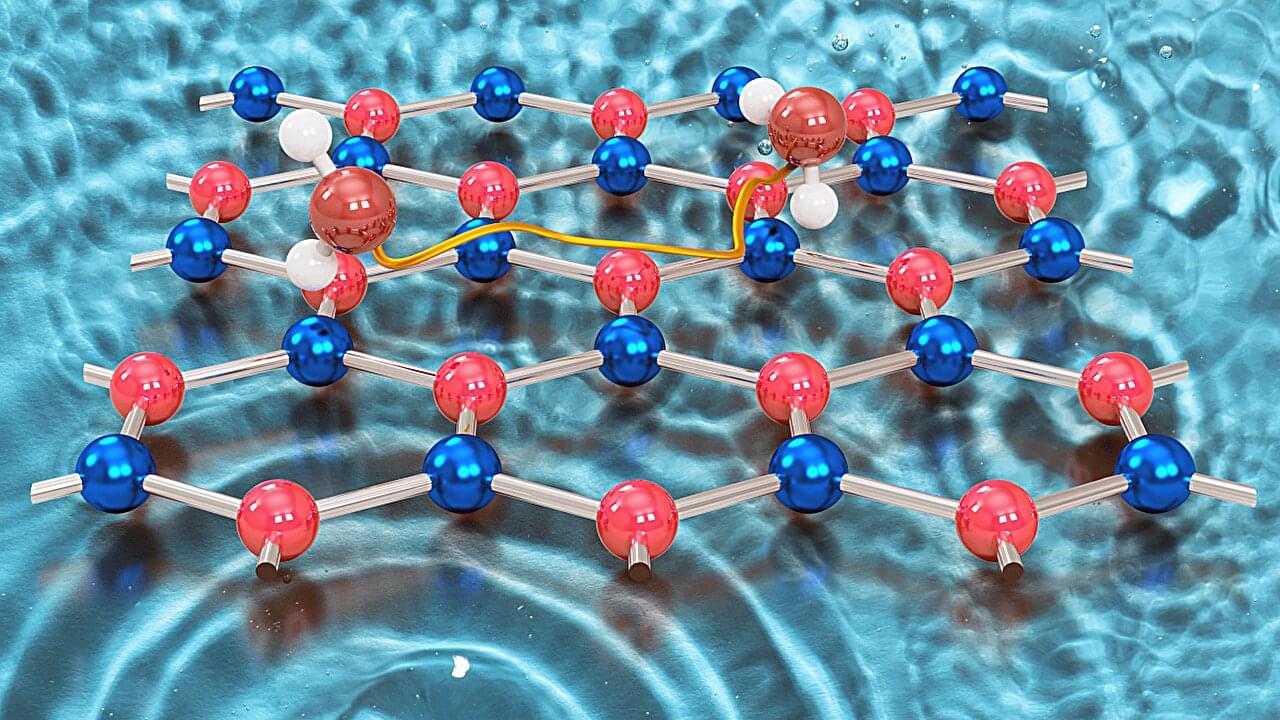

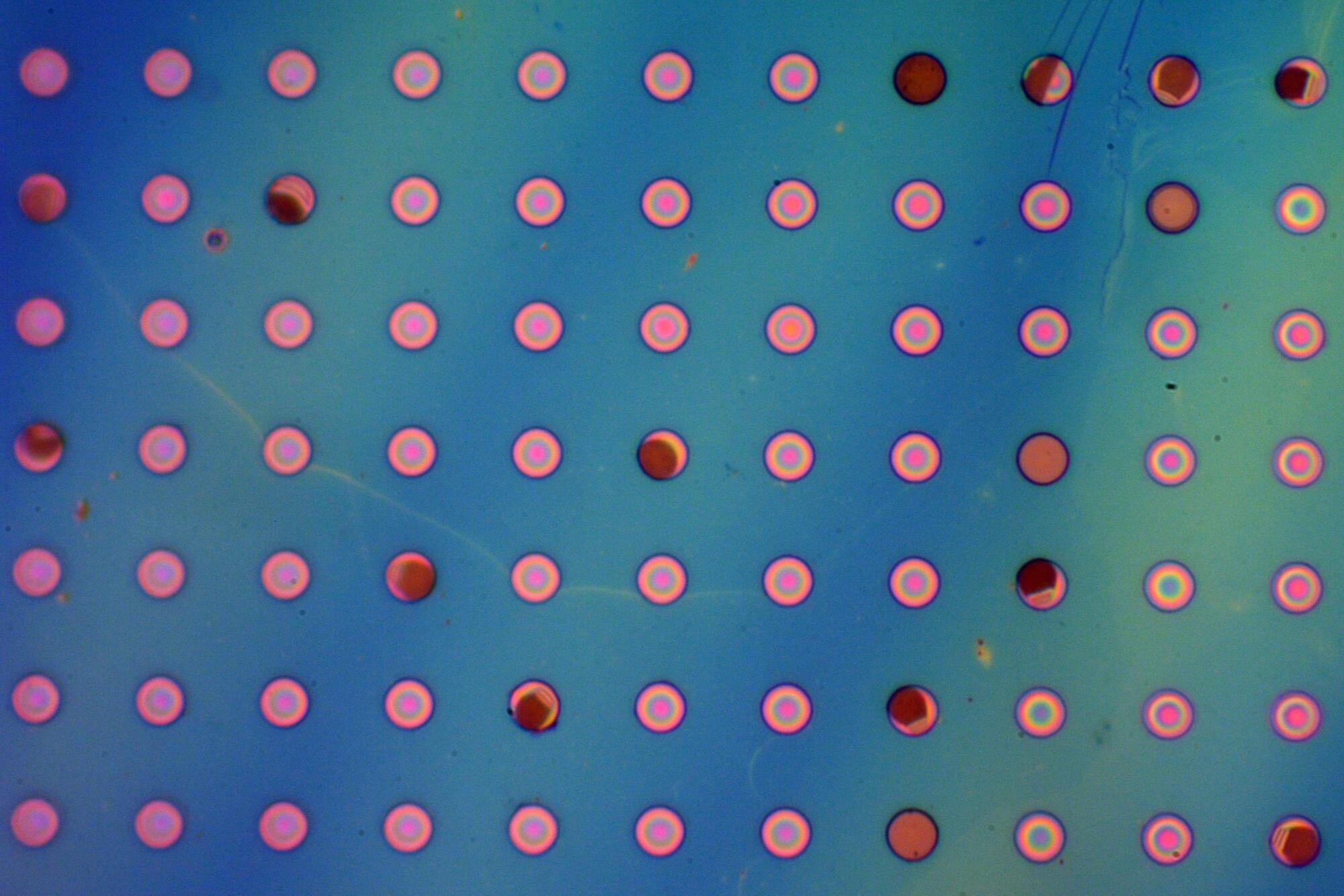

A surprising discovery about how water behaves on one of the world’s thinnest 2D materials could lead to major technological improvements, from better anti-icing coatings for aircraft and self-cleaning solar panels to next-generation lubricants and energy materials.

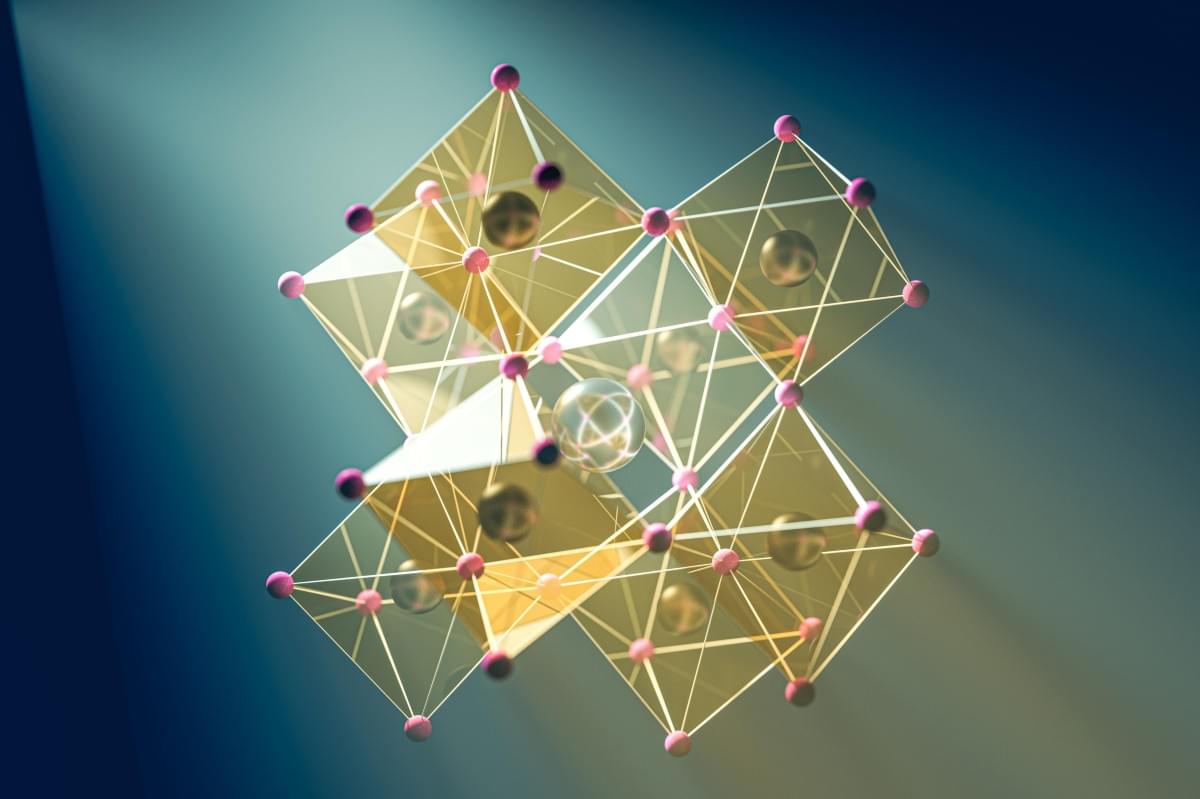

In a study published in Nature Communications, researchers from the University of Surrey and Graz University of Technology tested two ultra-thin sheet-like materials with a honeycomb structure— graphene and hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN). While graphene is electrically conductive—making it a key contender for future electronics, sensors and batteries—h-BN, often called “white graphite,” is a high-performance ceramic material and electrical insulator.