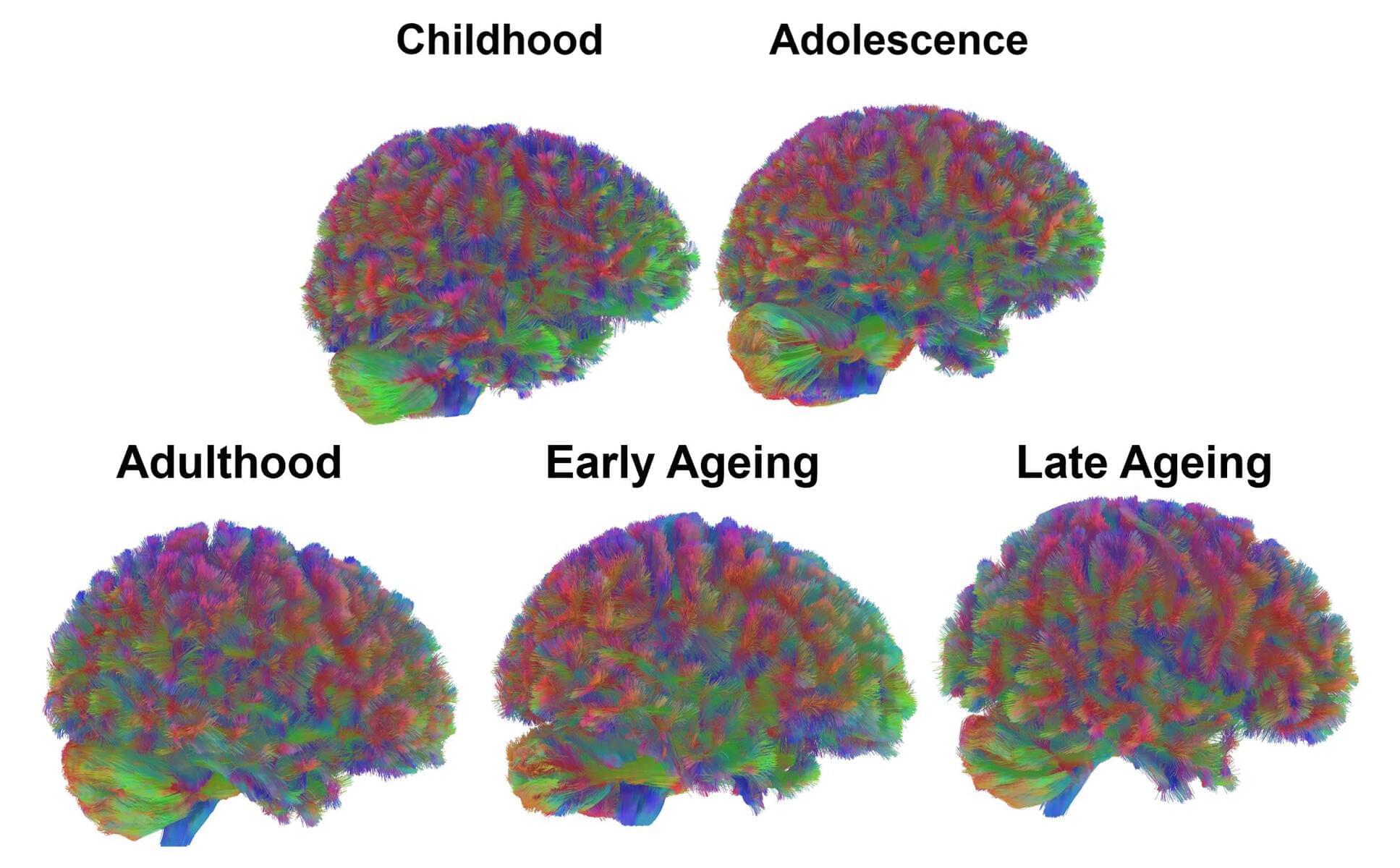

Recent technological and scientific advances have opened new possibilities for neuroscience research, which is in turn leading to interesting new discoveries. Over the past few years, many groups of neuroscientists worldwide have been trying to map the structure of the brain and its underlying regions with increasing precision, while also probing their involvement in specific mental functions.

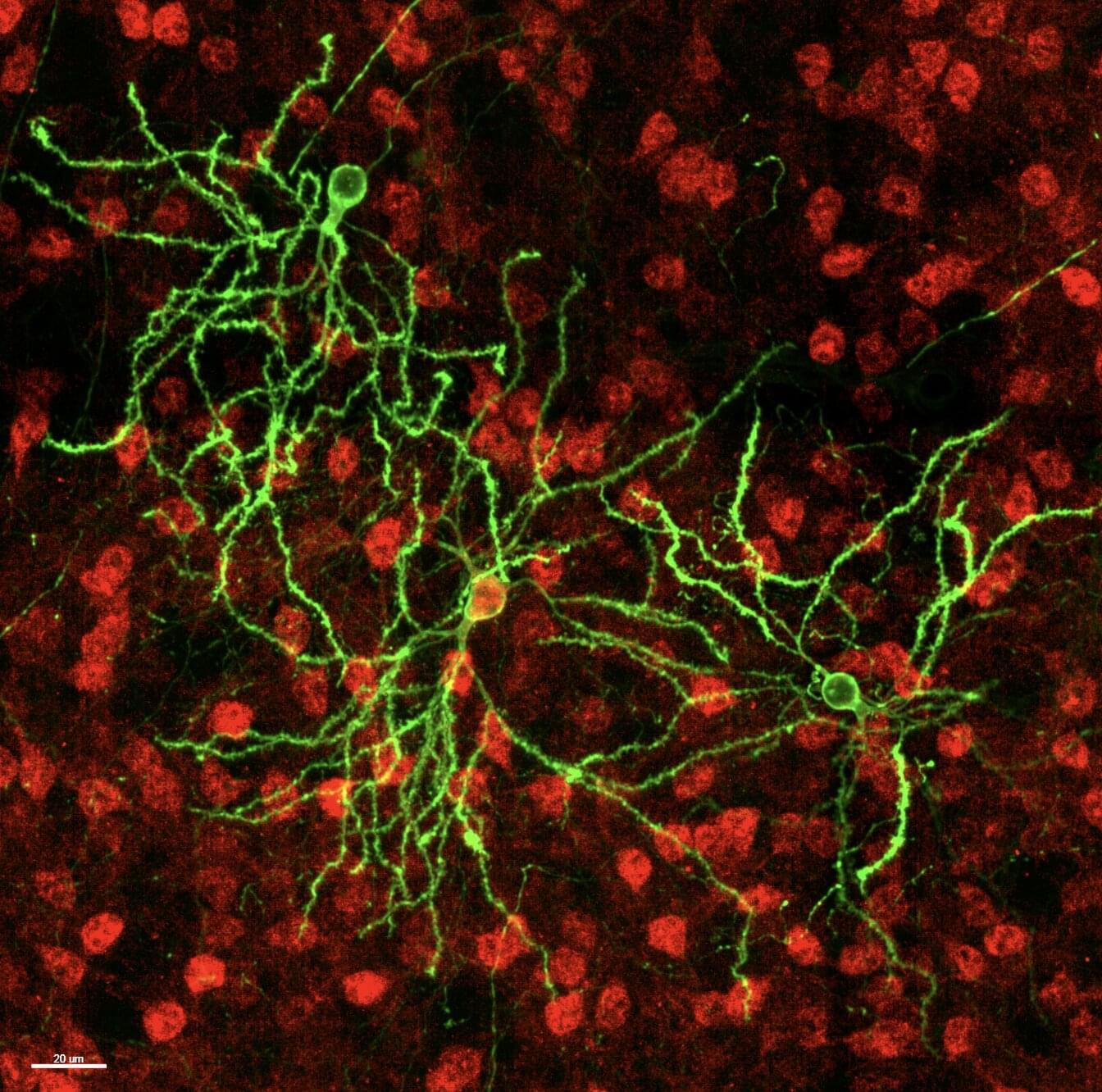

As mapping the human brain in detail is often challenging and requires significant resources, many studies focus on other mammals, particularly mice or other rodents. Most mouse brain atlases delineated to date map the density of neurons or other brain cells (i.e., how many cells are packed in specific parts of the brain). In contrast, fewer works also tried to map the shape of neurons in the mouse brain and interactions between them.

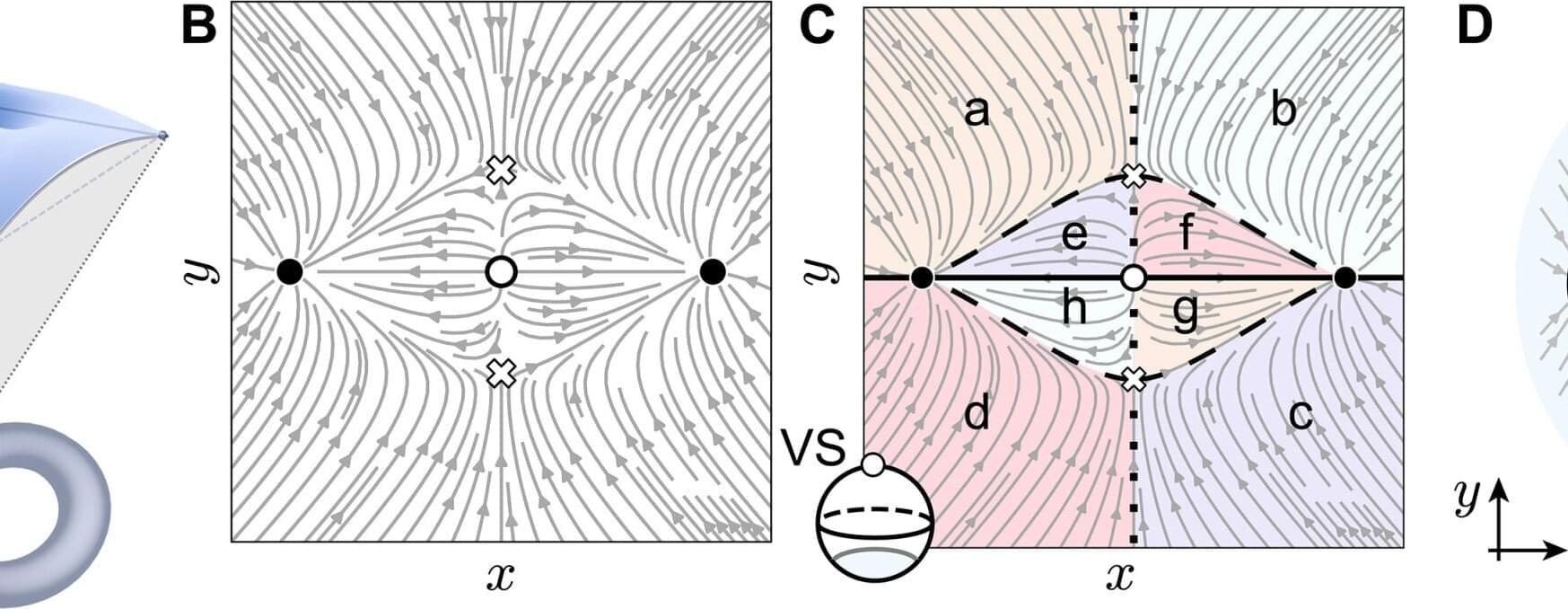

Researchers at Fudan University and Southeast University recently set out to map dendrites (i.e., branch-like extensions of neurons via which they receive signals from other cells) in the mouse brain. Their paper, published in Nature Neuroscience, unveils groups of structures in the mouse brain that influence how neurons function and connect to other neurons, also known as microenvironments.