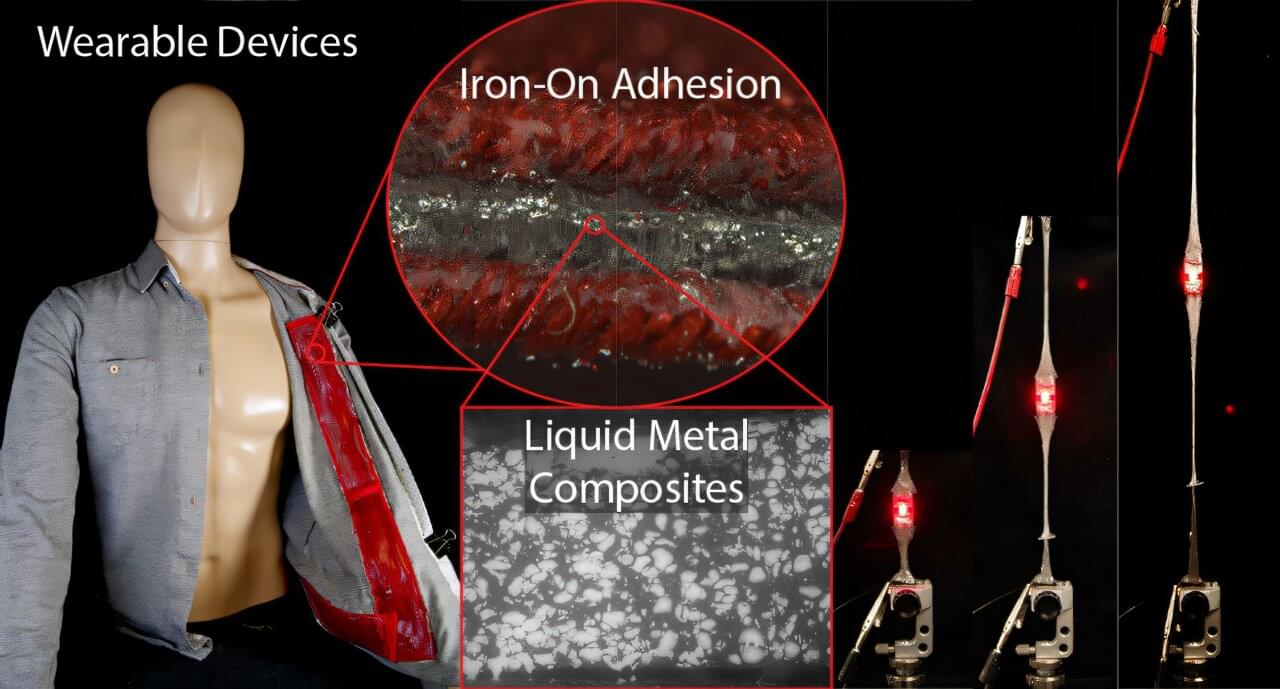

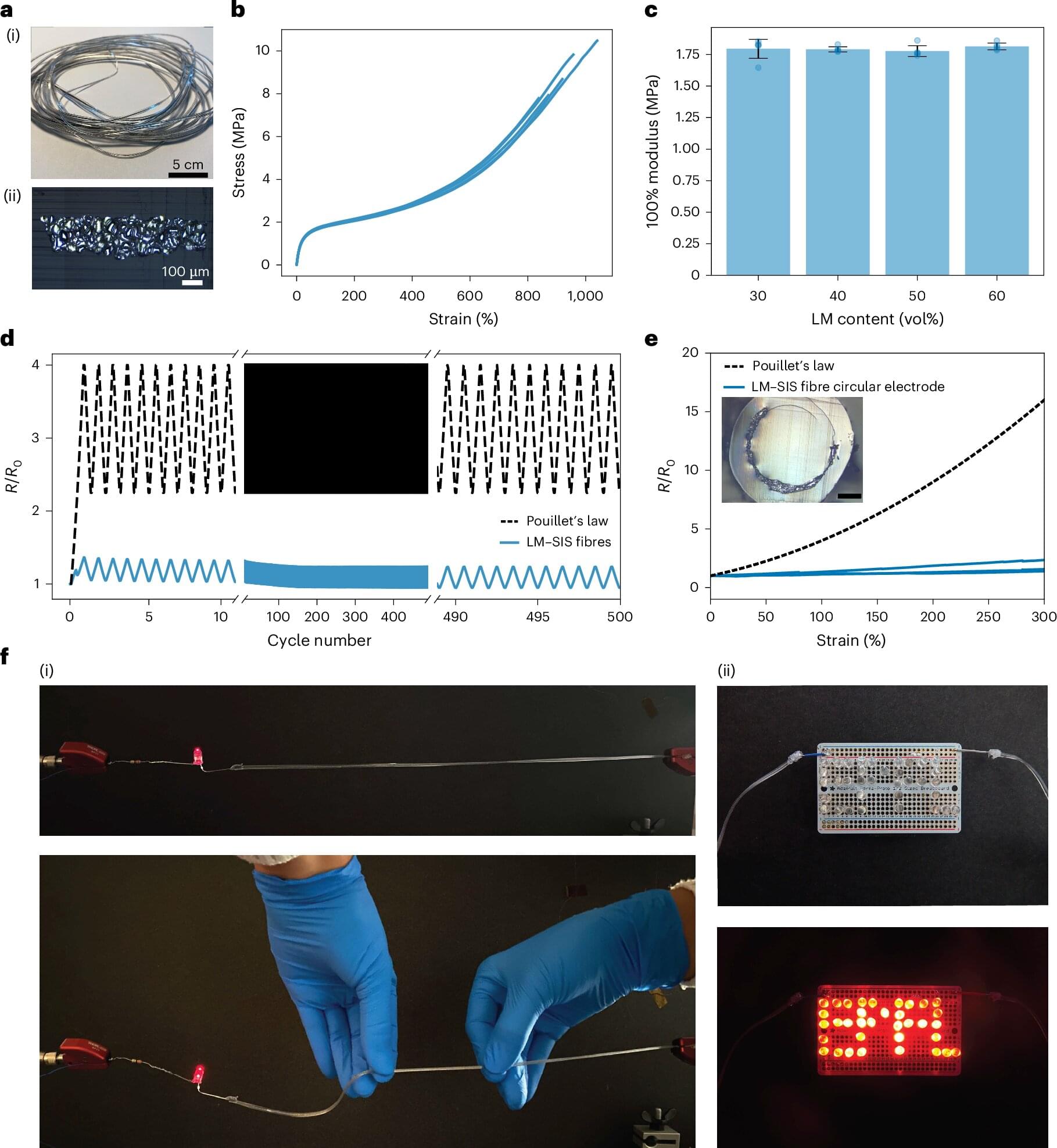

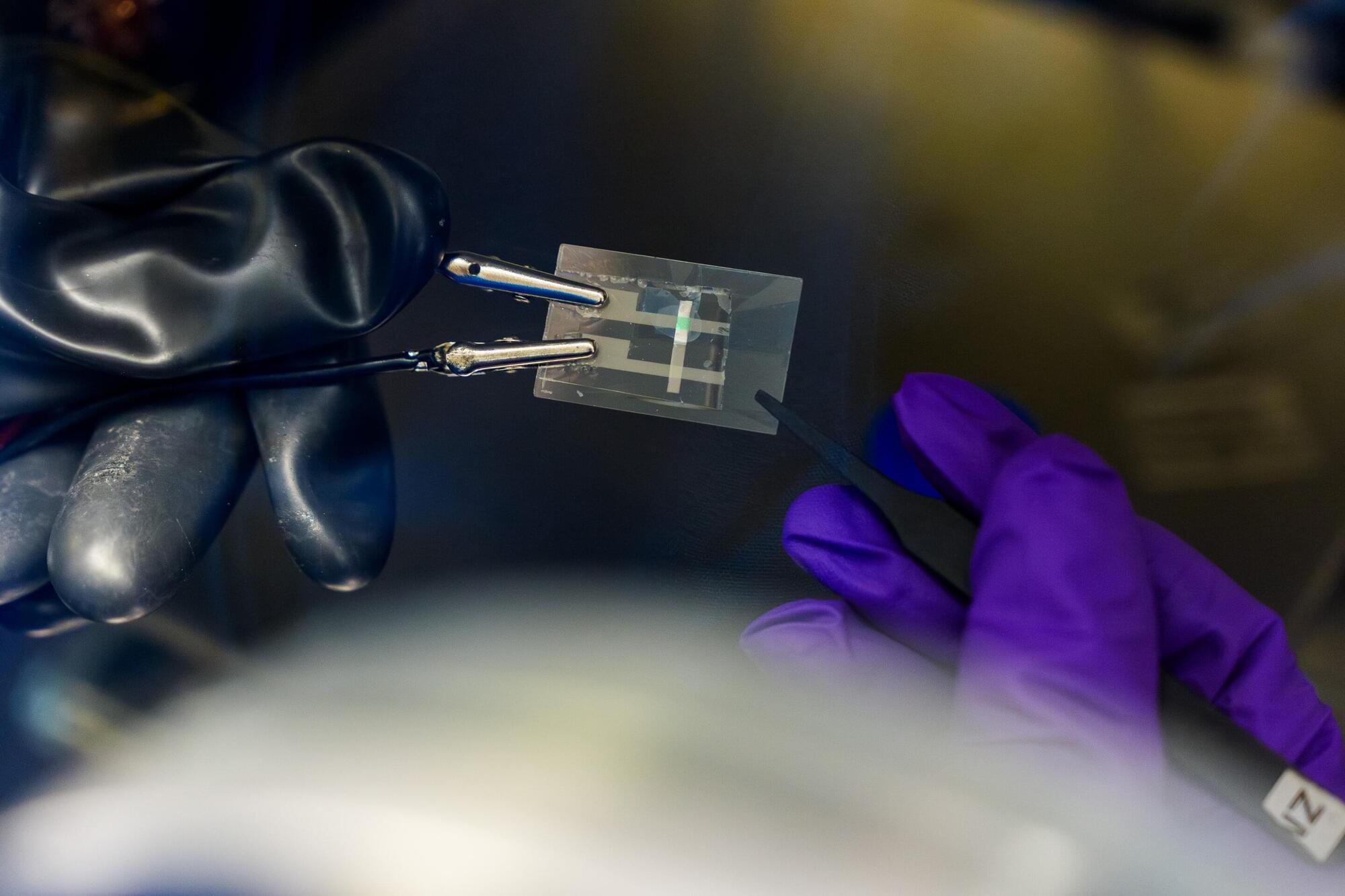

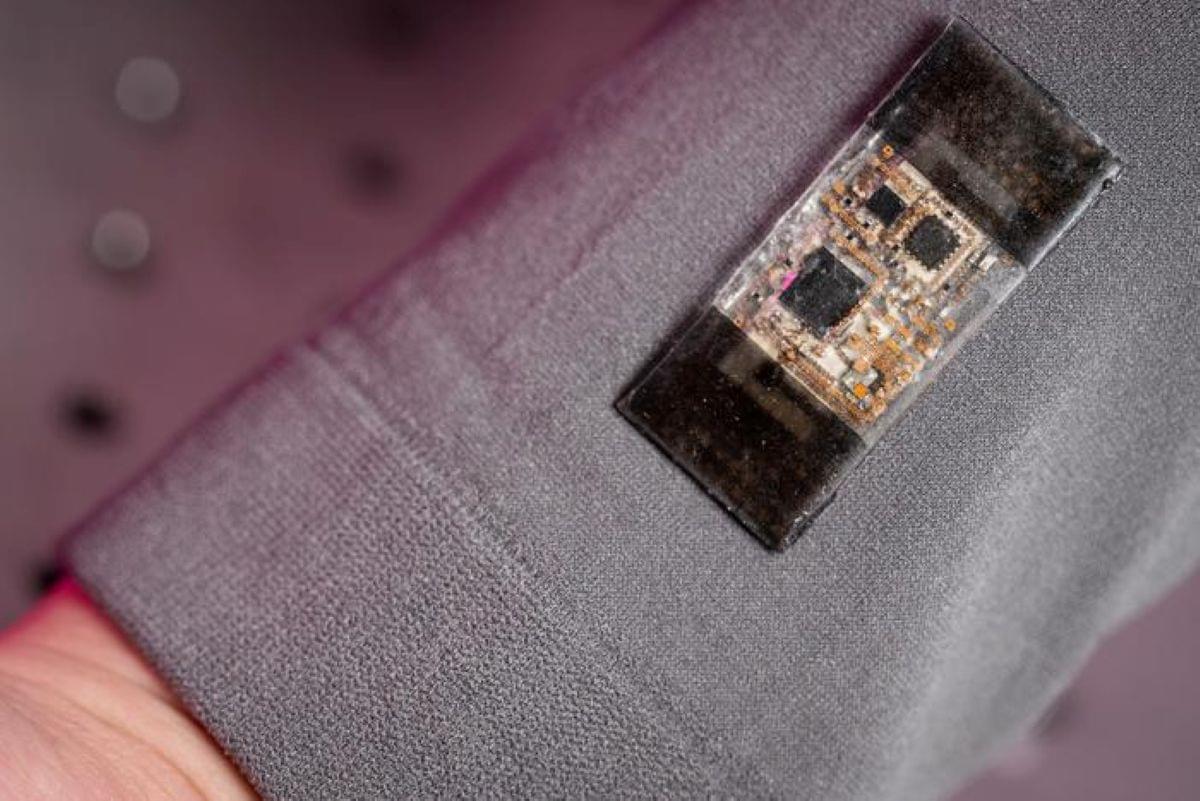

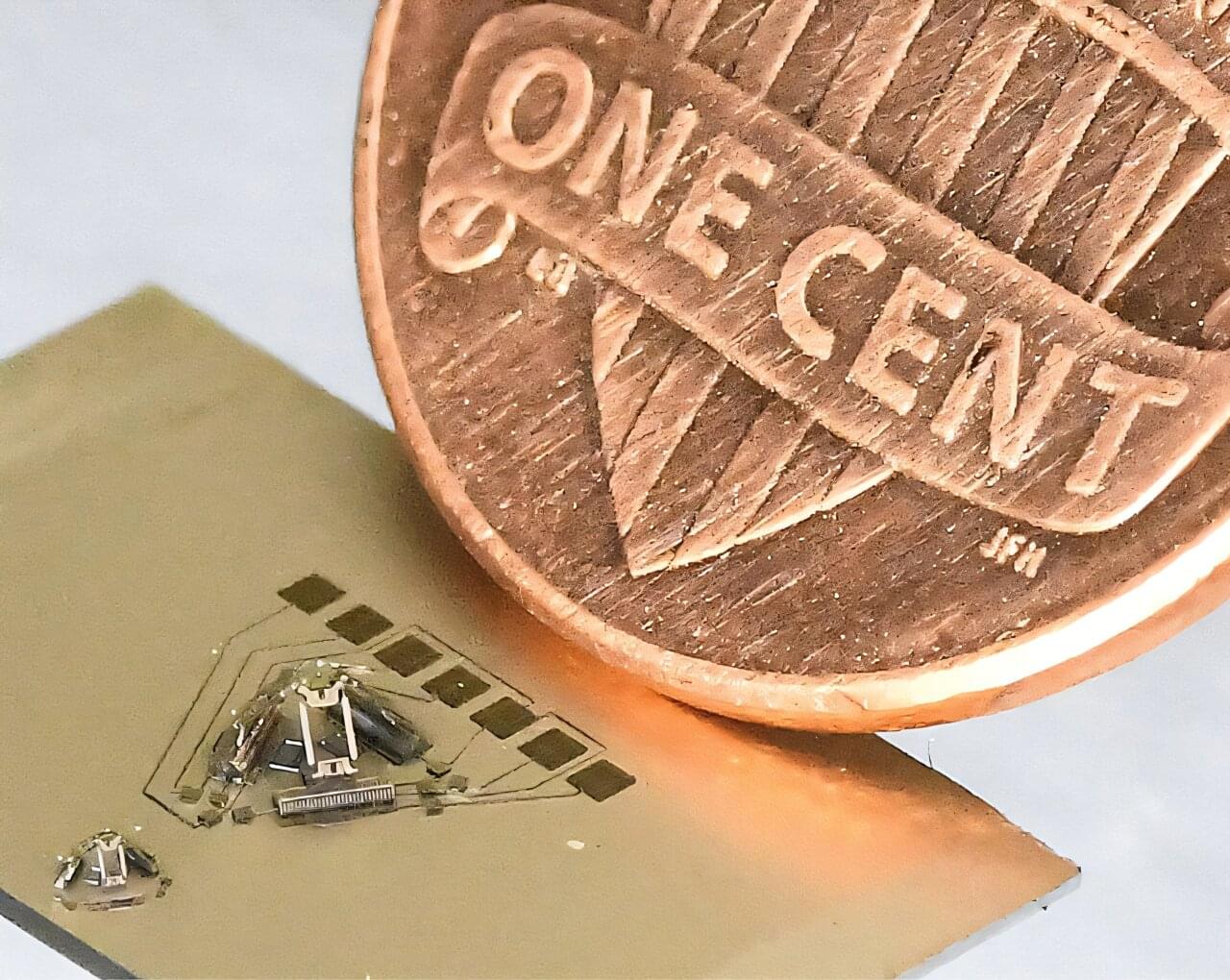

Iron-on patches can repair clothing or add personal flair to backpacks and hats. And now they could power wearable tech, too. Researchers reporting in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces have combined liquid metal and a heat-activated adhesive to create an electrically conductive patch that bonds to fabric when heated with a hot iron. In demonstrations, circuits ironed onto a square of fabric lit up LEDs and attached an iron-on microphone to a button-up shirt.

“E-textiles and wearable electronics can enable diverse applications from health care and environmental monitoring to robotics and human-machine interfaces. Our work advances this exciting area by creating iron-on soft electronics that can be rapidly and robustly integrated into a wide range of fabrics,” says Michael D. Bartlett, a researcher at Virginia Tech and corresponding author on the study.