In December 1954, Gertrude Elion and colleagues described a new compound they had developed that sent children with leukemia into remission. It would guide a new approach to “rational drug design.”

As we expected, the “Vista” supercomputer that the Texas Advanced Computing Center installed last year as a bridge between the current “Stampede-3” and “Frontera” production system and its future “Horizon” system coming next year was indeed a precursor of the architecture that TACC would choose for the Horizon machine.

What TACC does – and doesn’t do – matters because as the flagship datacenter for academic supercomputing at the National Science Foundation, the company sets the pace for those HPC organizations that need to embrace AI and that have not only large jobs that require an entire system to run (so-called capability-class machines) but also have a wide diversity of smaller jobs that need to be stacked up and pushed through the system (making it also a capacity-class system). As the prior six major supercomputers installed at TACC aptly demonstrate, you can have the best of both worlds, although you do have to make different architectural choices (based on technology and economics) to accomplish what is arguably a tougher set of goals.

Some details of the Horizon machine were revealed at the SC25 supercomputing conference last week, which we have been mulling over, but there are still a lot of things that we don’t know. The Horizon that will be fired up in the spring of 2026 is a bit different than we expected, with the big change being a downshift from an expected 400 petaflops of peak FP64 floating point performance down to 300 petaflops. TACC has not explained the difference, but it might have something to do with the increasing costs of GPU-accelerated systems. As far as we know, the budget for the Horizon system, which was set in July 2024 and which includes facilities rental from Sabey Data Centers as well as other operational costs, is still $457 million. (We are attempting to confirm this as we write, but in the wake of SC25 and ahead of the Thanksgiving vacation, it is hard to reach people.)

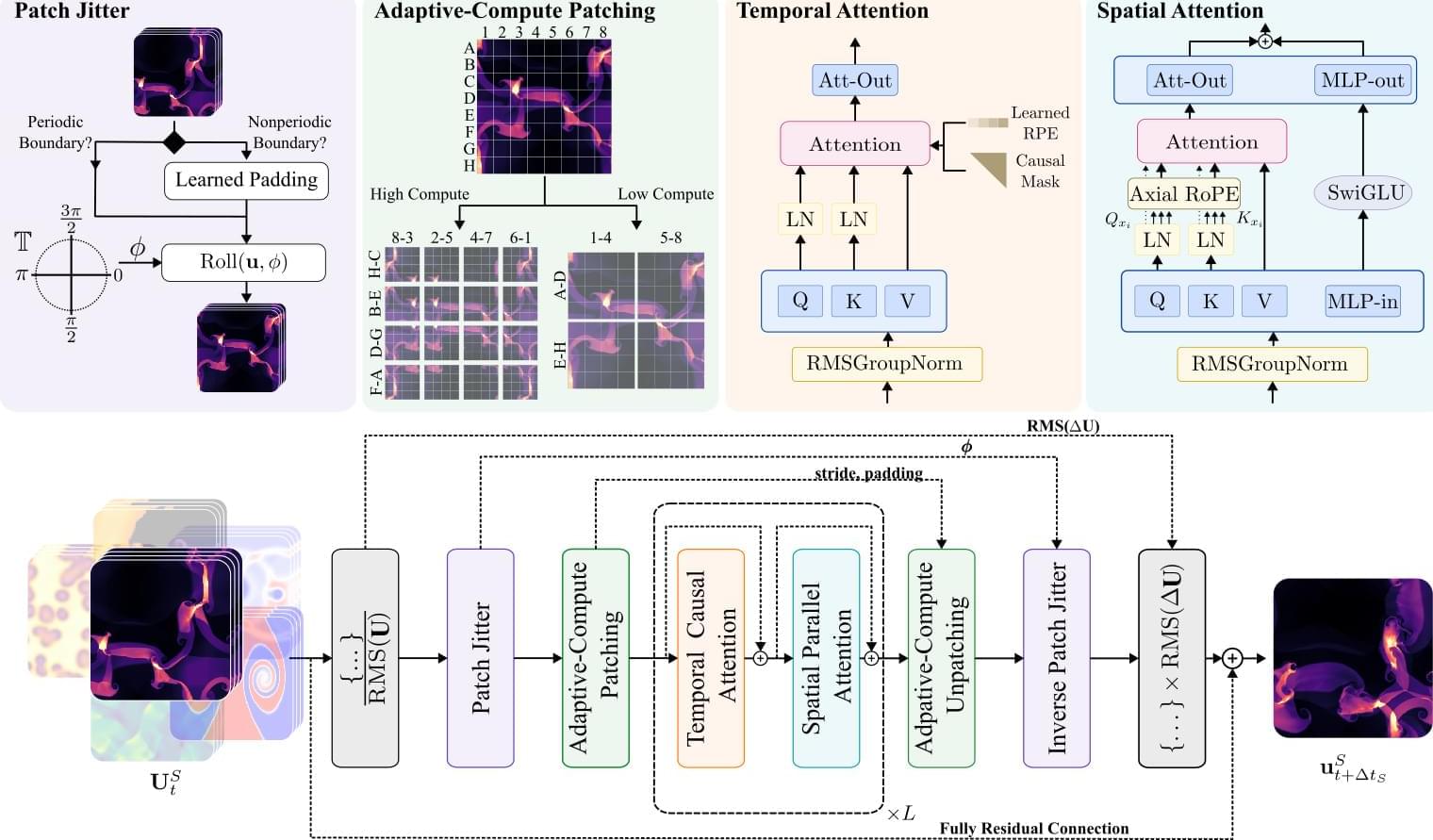

Using simulation-based techniques, scientists can ask how their ideas, actions, and designs will interact with the physical world. Yet this power is not without costs. Cutting edge simulations can often take months of supercomputer time. Surrogate models and machine learning are promising alternatives for accelerating these workflows, but the data hunger of machine learning has limited their impact to data-rich domains. Over the last few years, researchers have sought to side-step this data dependence through the use of foundation models— large models pretrained on large amounts of data which can accelerate the learning process by transferring knowledge from similar inputs, but this is not without its own challenges.

All of modern mathematics is built on the foundation of set theory, the study of how to organize abstract collections of objects. But in general, research mathematicians don’t need to think about it when they’re solving their problems. They can take it for granted that sets behave the way they’d expect, and carry on with their work.

Descriptive set theorists are an exception. This small community of mathematicians never stopped studying the fundamental nature of sets — particularly the strange infinite ones that other mathematicians ignore.

Their field just got a lot less lonely. In 2023, a mathematician named Anton Bernshteyn (opens a new tab) published a deep and surprising connection (opens a new tab) between the remote mathematical frontier of descriptive set theory and modern computer science.