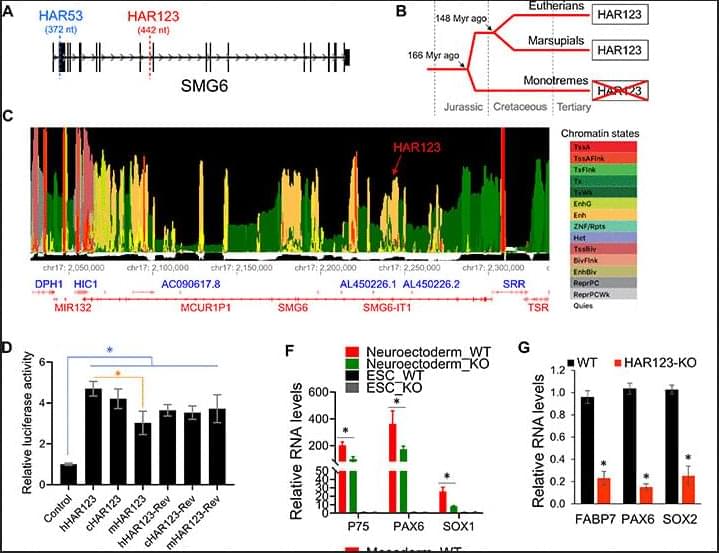

HAR123 is a conserved enhancer rapidly evolving in the human lineage that exerts neural functions.

Research on exercise and brain disorders has traditionally focused on its direct regulatory effects on neurons and synapses, neglecting peripheral organ-mediated pathways. To address this gap, this review proposes the novel concept of the “multi-organ-brain axis.” This concept posits that during brain disorders, functional alterations in peripheral organs such as skeletal muscle, heart, liver, adipose tissue, and spleen can disrupt metabolic and immune homeostasis, thereby bidirectionally modulating brain function via signaling molecules and metabolites.

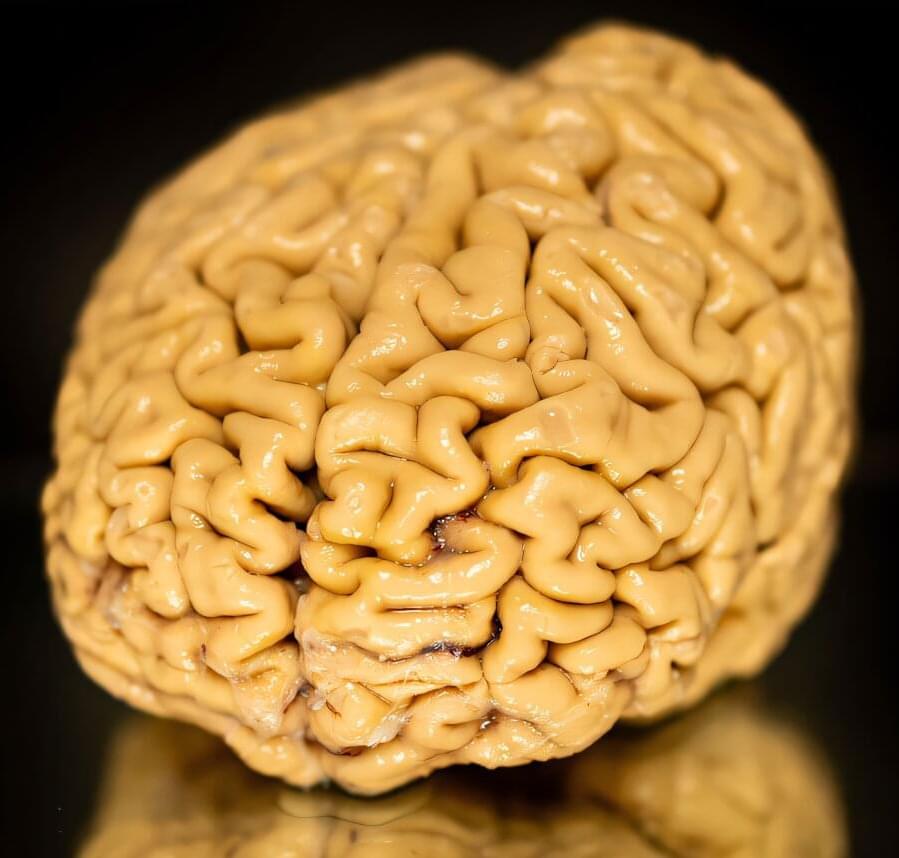

For 25 years, scientists at Northwestern Medicine have been studying individuals aged 80 and older—dubbed “SuperAgers”—to better understand what makes them tick.

These unique individuals, who show outstanding memory performance at a level consistent with individuals who are at least three decades younger, challenge the long-held belief that cognitive decline is an inevitable part of aging.

Over the quarter-century of research, the scientists have seen some notable lifestyle and personality differences between SuperAgers and those aging typically—such as being social and gregarious—but “it’s really what we’ve found in their brains that’s been so earth-shattering for us,” said Dr. Sandra Weintraub, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and neurology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.