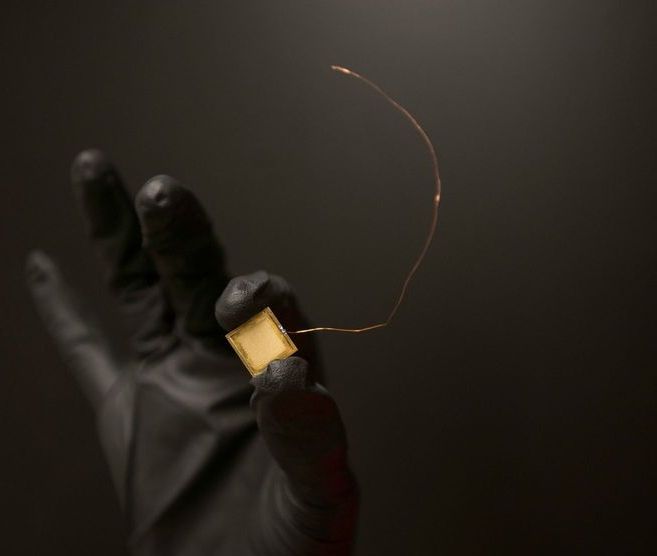

Ion propulsion company Accion Systems has raised $11 million in its latest funding round and has launches and contracts planned this year with NASA, the DoD and academic institutions.

Nearly 14 months ago, Vice President Mike Pence spoke at a meeting of the National Space Council in Huntsville, Alabama, and changed the trajectory of NASA’s human spaceflight program. Pence directed NASA to accelerate its schedule for returning humans to the Moon, which at the time called for a landing by 2028. The new goal: land American astronauts on the Moon “within the next five years,” a goal subsequently interpreted to mean by the end of 2024 (see “Lunar whiplash”, The Space Review, April 1, 2019.)

Much of what NASA needed to accomplish the revised goal was already in development, notably the Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System. Both had suffered significant delays but (presumably) would be ready in time to launch NASA astronauts to orbit the Moon, perhaps using the lunar Gateway also under development. What was missing, though, was that last, but most essential, element: a lander to take astronauts down to the surface and then return them to lunar orbit.

No longer. On April 30, NASA announced it had awarded contracts to three companies for its Human Landing System (HLS) program. The awards to Blue Origin, Dynetics, and SpaceX, with a cumulative value of $967 million, will fund initial studies for human lunar lander concepts over the next ten months. NASA will then select one or more companies for full-scale lander development, with the goal of having a lander ready for the Artemis 3 mission before the end of 2024.

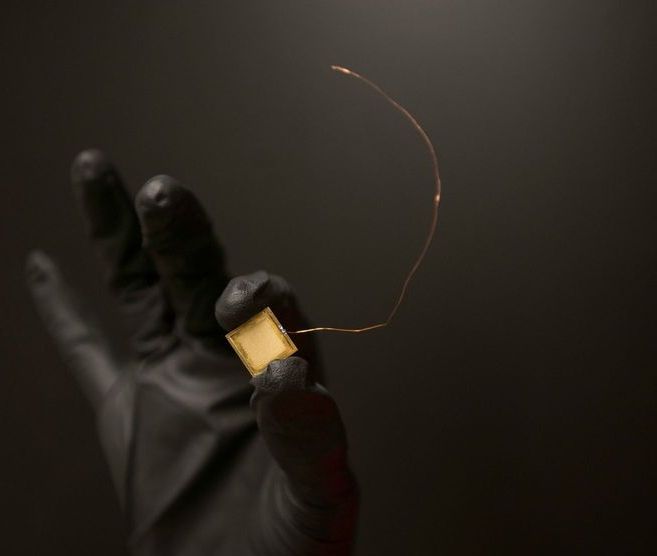

Here’s a step-by-step explainer of what will happen during the Demo-2 mission, from prelaunch preparations through the astronauts’ return to Earth.

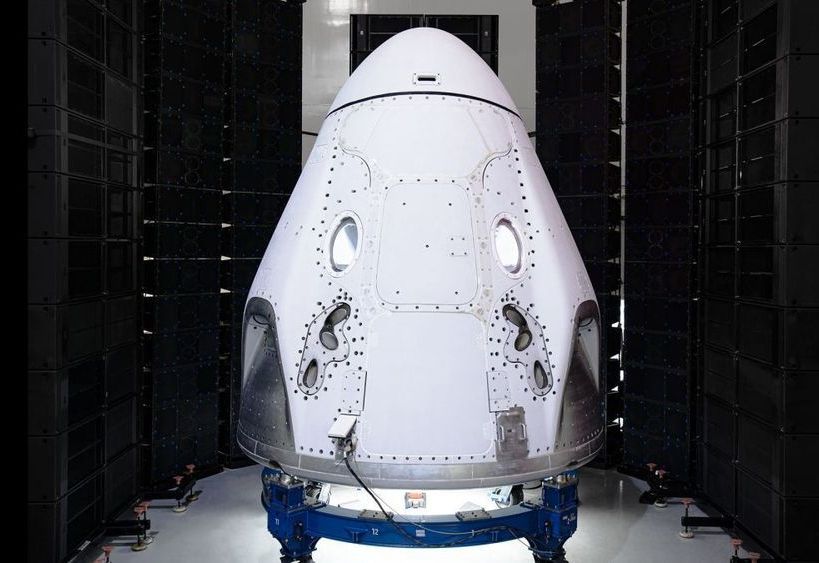

In photos: SpaceX’s Demo-2 Crew Dragon test flight with astronauts

While NASA astronauts heading to their rockets on the day of a launch have traditionally traveled to their launchpads in a retro-style “Astrovan,” Demo-2 astronauts Doug Hurley (left) and Bob Behnken will be rolling up to their Falcon 9 rocket in shiny Tesla Model X sports cars. This comes as no surprise to SpaceX fans; Elon Musk, the founder of both SpaceX and Tesla, famously launched a cherry-red Tesla Roadster into space on a Falcon Heavy rocket in 2018.

Since the ancient times, humans have been observant and curious to know why everything around us exists. Looking up into the sky, we see many celestial objects such as stars and planets. In the past few centuries, we have made many jumps in the field of space exploration. Telescopes have been created, the stars have been mapped, people have flown in space and even lived there for over six months. These activities have played a major role in the development of our knowledge about space, yet there is so much more we need to discover.

One thing we need to find is how to make space travel quicker and more efficient. Why making space travel better, out of all the problems mankind faces? Currently, our global population is about 7.6 billion and is exponentially rising. By 2025, in just seven years, the global population will be roughly 8.1 billion. Since our resource availability is going down and our population is rising, the Earth can not sustain such an imbalance. This why we must start looking to live on other planets and in order to do this, shortening the time it takes to reach such planets is a necessity.

As a society, when we think of space in general, we just think “oh yeah, that’s cool” but there are multiple problems with space travel. One major issue is the lack of experience. The last Moon landing was in 1972 and space shuttles have been out of use 2011. We can’t just get up and say “you know what, let’s go to space” as it takes many years of preparation and training. This ties to two other major problems:

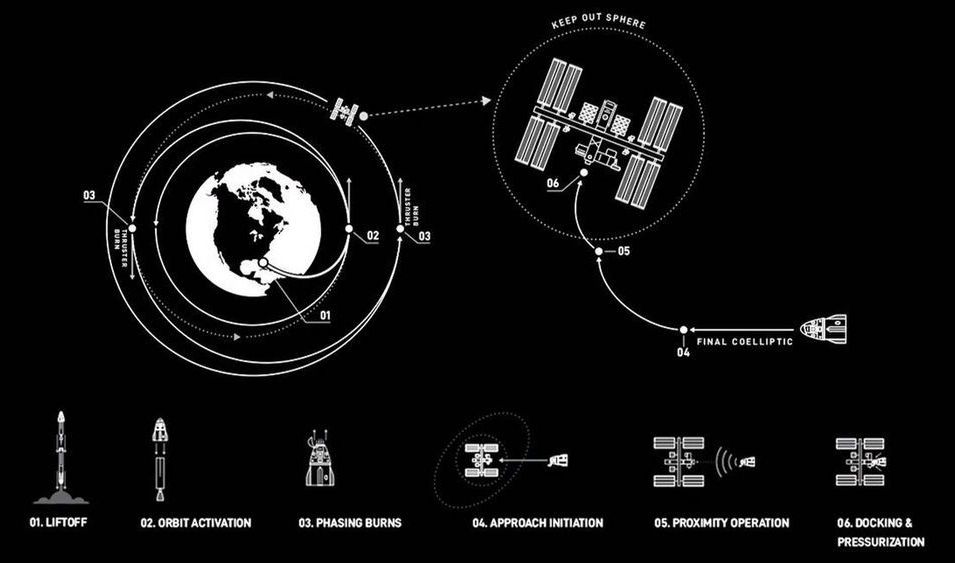

“Submit your photo today to fly with the crew on Dragon and commemorate your achievements!” SpaceX wrote on its website.

Related: In photos: SpaceX’s historic Demo-2 test flight with astronauts More: How SpaceX’s Crew Dragon space capsule works (infographic)

Together with SpaceX, we will return human spaceflight to American soil after nearly a decade. May 27th is not only a big day for our teams – it’s a big day for our country.

What does our upcoming NASA Commercial Crew Program mission mean to YOU? Here’s how to submit your responses using #LaunchAmerica : https://go.nasa.gov/2Wk2opU

Watch the full trailer: https://go.nasa.gov/35LLaov

SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft is less than two weeks from launching NASA astronauts to the International Space Station for the first time, but some big obstacles still stand in the way.

With this SpaceX mission, known as Demo-2, veteran NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley are set to launch on a Falcon 9 rocket from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center on May 27. The historic launch will be the first crewed launch from the United States to orbit since NASA’s space shuttle program ended in 2011.