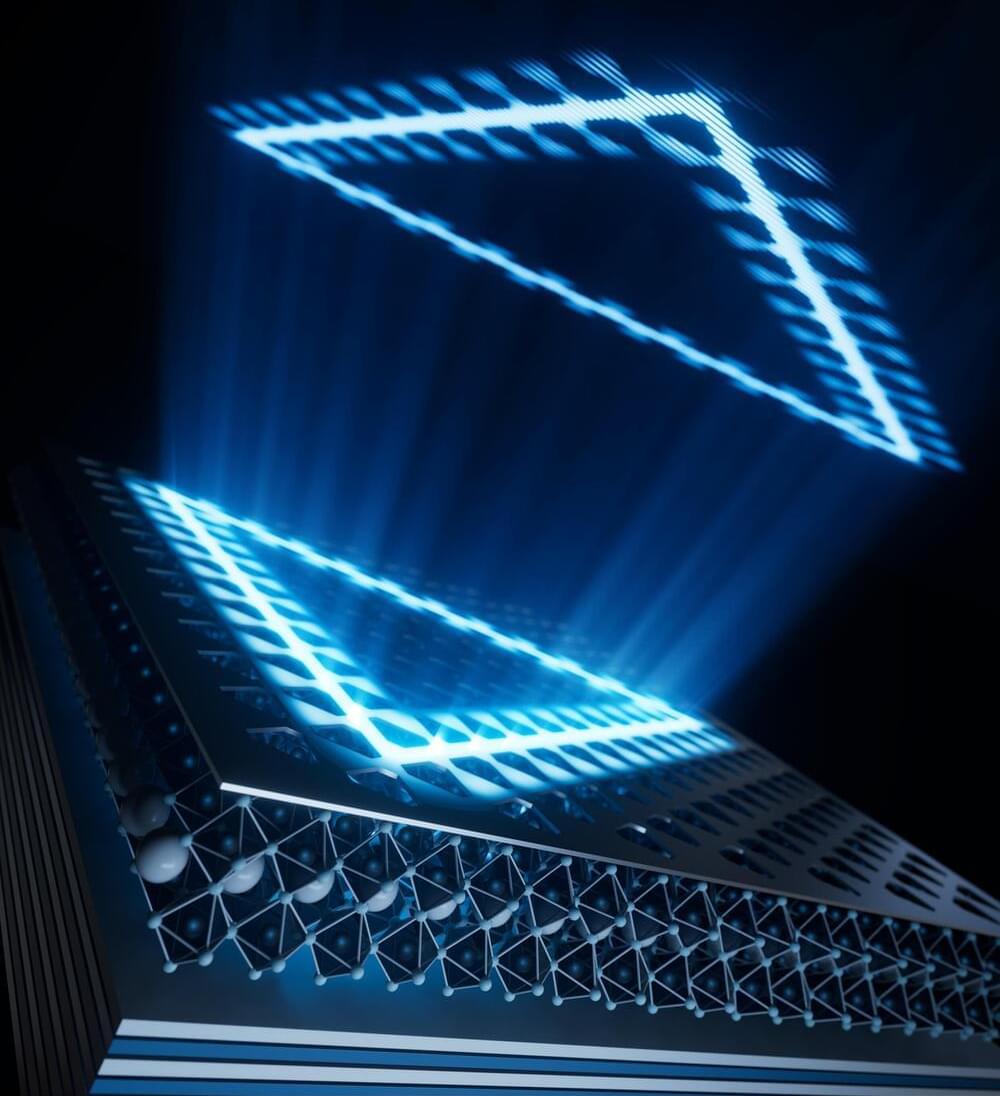

In a study published in Nature Materials, scientists from the University of California, Irvine describe a new method to make very thin crystals of the element bismuth – a process that may aid in making the manufacturing of cheap flexible electronics an everyday reality.

“Bismuth has fascinated scientists for over a hundred years due to its low melting point and unique electronic properties,” said Javier Sanchez-Yamagishi, assistant professor of physics & astronomy at UC Irvine and a co-author of the study. “We developed a new method to make very thin crystals of materials such as bismuth, and in the process reveal hidden electronic behaviors of the metal’s surfaces.”

The bismuth sheets the team made are only a few nanometers thick. Sanchez-Yamagishi explained how theorists have predicted that bismuth contains special electronic states allowing it to become magnetic when electricity flows through it – something essential for quantum electronic devices based on the magnetic spin of electrons.