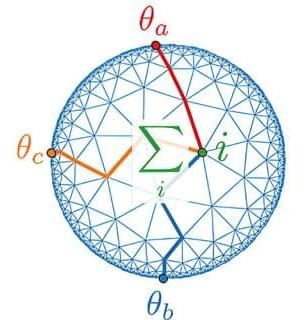

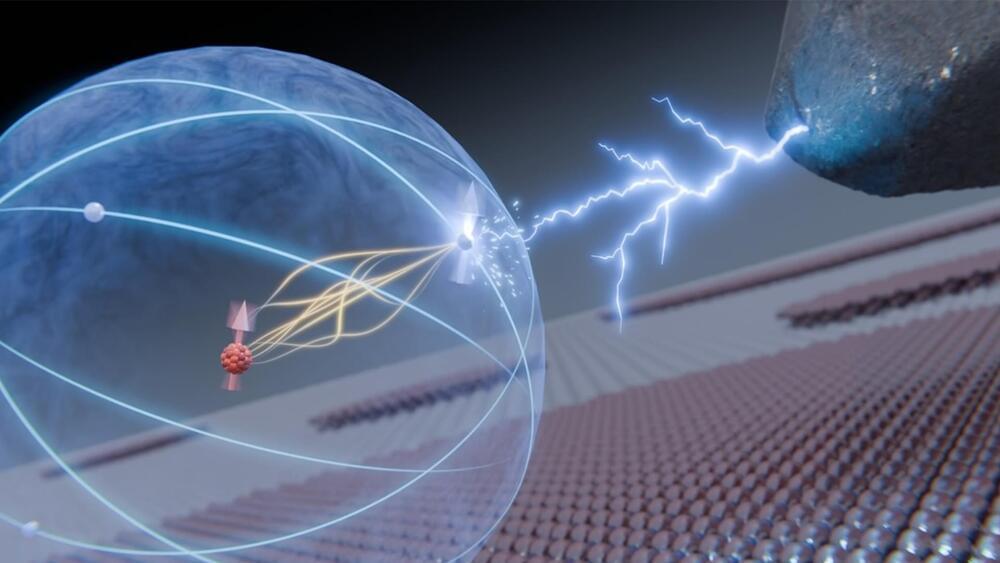

Researchers Propose a #Smaller, more #Noise-#Tolerant #Quantum #Circuit for #Cryptography.

MIT researchers new algorithm is as fast as Regev’s, requires fewer qubits, and has a higher tolerance to quantum noise, making it more feasible to implement…

The most recent email you sent was likely encrypted using a tried-and-true method that relies on the idea that even the fastest computer would be unable to efficiently break a gigantic number into factors.

Quantum computers, on the other hand, promise to rapidly crack complex cryptographic systems that a classical computer might never be able to unravel. This promise is based on a quantum factoring algorithm proposed in 1994 by Peter Shor, who is now a professor at MIT.

But while researchers have taken great strides in the last 30 years, scientists have yet to build a quantum computer powerful enough to run Shor’s algorithm.