An analog-digital approach to quantum simulation could lay the foundations for the next generation of supercomputers to finally outpace their classical predecessors.

A recent study led by quantum researchers at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory proved popular among the science community interested in building a more reliable quantum network.

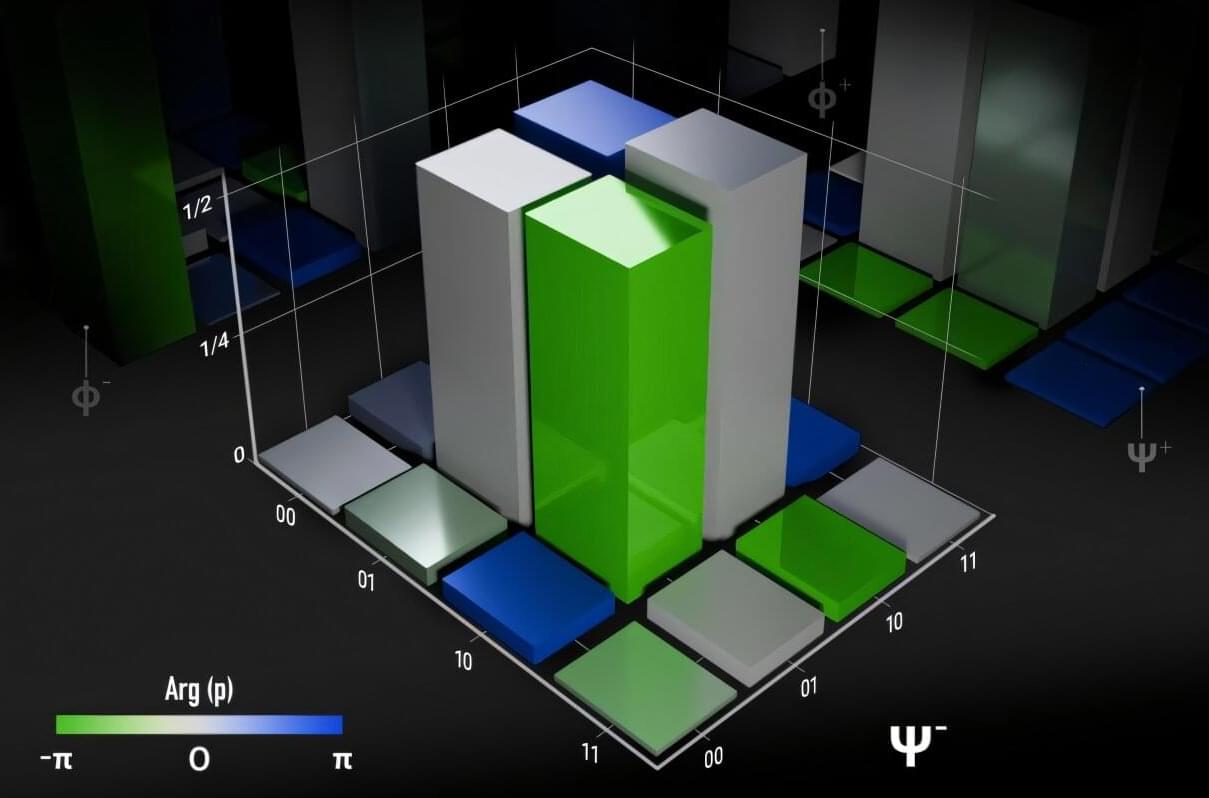

The study, led by ORNL’s Hsuan-Hao Lu, details development of a novel quantum gate that operates between two photonic degrees of freedom—polarization and frequency. (Photonic degrees of freedom describe different properties of a photon that can be controlled and used to store or transmit information.) When combined with hyperentanglement, this new approach could enhance error resilience in quantum communication, helping to pave the way for future quantum networks.

Their work was published in the journal Optica Quantum.

Quantum spin liquids (QSLs) are fascinating and mysterious states of matter that have intrigued scientists for decades. First proposed by Nobel laureate Philip Anderson in the 1970s, these materials break the conventional rules of magnetism by never settling into a stable magnetic state, even at temperatures close to absolute zero.

Instead, the spins of the atoms within them remain constantly fluctuating and entangled, creating a kind of magnetic “liquid.” This unusual behavior is driven by a phenomenon called magnetic frustration, where competing forces prevent the system from reaching a single, ordered configuration.

QSLs are notoriously difficult to study. Unlike ordinary magnetic materials, they don’t show the usual signs of magnetic transitions, which makes it hard to detect and understand them using traditional techniques. As a result, their behavior has remained an elusive puzzle for researchers.

The advent of quantum simulators in various platforms8,9,10,11,12,13,14 has opened a powerful experimental avenue towards answering the theoretical question of thermalization5,6, which seeks to reconcile the unitarity of quantum evolution with the emergence of statistical mechanics in constituent subsystems. A particularly interesting setting is that in which a quantum system is swept through a critical point15,16,17,18, as varying the sweep rate can allow for accessing markedly different paths through phase space and correspondingly distinct coarsening behaviour. Such effects have been theoretically predicted to cause deviations19,20,21,22 from the celebrated Kibble–Zurek (KZ) mechanism, which states that the correlation length ξ of the final state follows a universal power-law scaling with the ramp time tr (refs. 3, 23,24,25).

Whereas tremendous technical advancements in quantum simulators have enabled the observation of a wealth of thermalization-related phenomena26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35, the analogue nature of these systems has also imposed constraints on the experimental versatility. Studying thermalization dynamics necessitates state characterization beyond density–density correlations and preparation of initial states across the entire eigenspectrum, both of which are difficult without universal quantum control36. Although digital quantum processors are in principle suitable for such tasks, implementing Hamiltonian evolution requires a high number of digital gates, making large-scale Hamiltonian simulation infeasible under current gate errors.

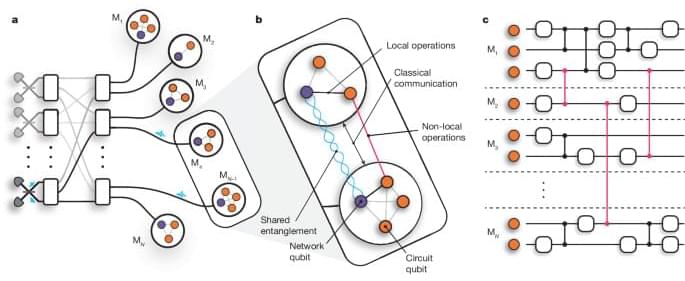

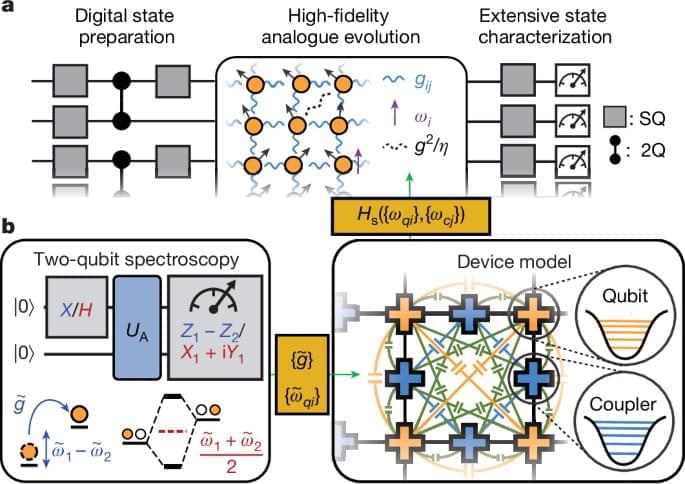

In this work, we present a hybrid analogue–digital37,38 quantum simulator comprising 69 superconducting transmon qubits connected by tunable couplers in a two-dimensional (2D) lattice (Fig. 1a). The quantum simulator supports universal entangling gates with pairwise interaction between qubits, and high-fidelity analogue simulation of a U symmetric spin Hamiltonian when all couplers are activated at once. The low analogue evolution error, which was previously difficult to achieve with transmon qubits due to correlated cross-talk effects, is enabled by a new scalable calibration scheme (Fig. 1b). Using cross-entropy benchmarking (XEB)39, we demonstrate analogue performance that exceeds the simulation capacity of known classical algorithms at the full system size.

Whether you’re a surly gang of bosons or a law abiding fermion, what a perfectly chilly day for keeping cooling Quantums…and who best to talk Quantum coolness than Deutsches Zentrum für Luft-und Raumfahrt (DLR)’s Quantum Queen #LisaWoerner! I cannot FREAKING wait to be talking with her again today on I’m With (Stargate) Genius…live,…if you’re cool enough, that is!

This breakthrough overcomes a major challenge—scalability—by allowing small quantum devices to work together rather than trying to cram millions of qubits into a single machine. Using photonic links, they achieved quantum teleportation of logical gates across modules, essentially “wiring” them together. This distributed approach mirrors how supercomputers function, offering a flexible and upgradeable system.

First Distributed Quantum Computer

In a major step toward making quantum computing practical on a large scale, scientists at Oxford University Physics have successfully demonstrated distributed quantum computing for the first time. By connecting two separate quantum processors using a photonic network interface, they effectively created a single, fully integrated quantum computer. This breakthrough opens the door to solving complex problems that were previously impossible to tackle. Their findings were published today (February 5) in Nature.

More than 800 researchers, policy makers and government officials from around the world gathered in Paris this week to attend the official launch of the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ). Held at the headquarters of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), the two-day event included contributions from four Nobel prize-winning physicists – Alain Aspect, Serge Haroche, Anne l’Huillier and William Phillips.

Opening remarks came from Cephas Adjej Mensah, a research director in the Ghanaian government, which last year submitted the draft resolution to the United Nations for 2025 to be proclaimed as the IYQ. “Let us commit to making quantum science accessible to all,” Mensah declared, reminding delegates that the IYQ is intended to be a global initiative, spreading the benefits of quantum equitably around the world. “We can unleash the power of quantum science and technology to make an equitable and prosperous future for all.”

The keynote address was given by l’Huillier, a quantum physicist at Lund University in Sweden, who shared the 2023 Nobel Prize for Physics with Pierre Agostini and Ferenc Krausz for their work on attosecond pulses. “Quantum mechanics has been extremely successful,” she said, explaining how it was invented 100 years ago by Werner Heisenberg on the island of Helgoland. “It has led to new science and new technology – and it’s just the beginning.”

Researchers have used quantum physics and machine learning to quickly and accurately understand a mound of data – a technique, they say, could help extract meaning from gargantuan datasets.

Their method works on groundwater monitoring, and they’re trialling it on other fields like traffic management and medical imaging.

“Machine learning and artificial intelligence is a very powerful tool to look at datasets and extract features,” Dr Muhammad Usman, a quantum scientist at CSIRO, tells Cosmos.

Information has become increasingly important in understanding the physical world around us, from ordinary computers to the underlying principles of fundamental physics, including quantum theory. How can information help discern physics? What can physics contribute to understanding information? And what about quantum information?

Make a donation to Closer To Truth to help us continue exploring the world’s deepest questions without the need for paywalls: https://shorturl.at/OnyRq.

Free access to Closer to Truth’s library of 5,000 videos: http://bit.ly/376lkKN

Watch more interviews on quantum information science and quantum mechanics: https://bit.ly/3rs6ZVs.

Max Tegmark is Professor of Physics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He holds a BS in Physics and a BA in Economics from the Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden. He also earned a MA and PhD in physics from University of California, Berkeley.

Register for free at CTT.com for subscriber-only exclusives: http://bit.ly/2GXmFsP