The strange principle of quantum entanglement baffled Albert Einstein. Yet finally putting quantum weirdness to the ultimate test, and embracing the results, turned out to be a revolutionary idea

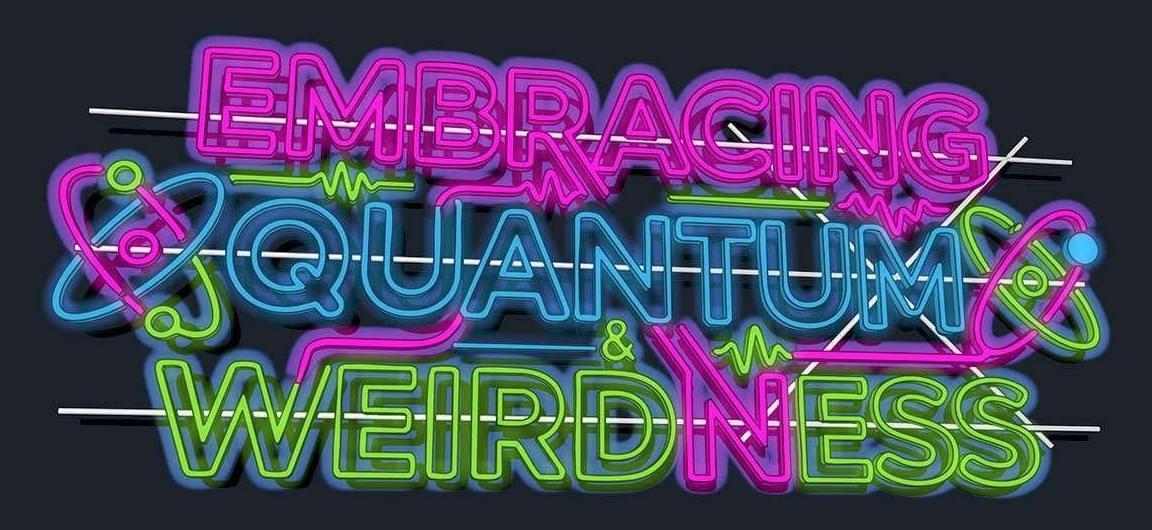

A team of researchers led by the University of Warwick has developed the first unified framework for detecting “spacetime fluctuations”—tiny, random distortions in the fabric of spacetime that appear in many attempts to unite quantum physics and gravity.

These subtle fluctuations, first envisaged by physicist John Wheeler, are thought to arise naturally in several leading theories of quantum gravity. But because different models of gravity predict different forms of these fluctuations, experimental teams have until now lacked clear guidance on what to look for.

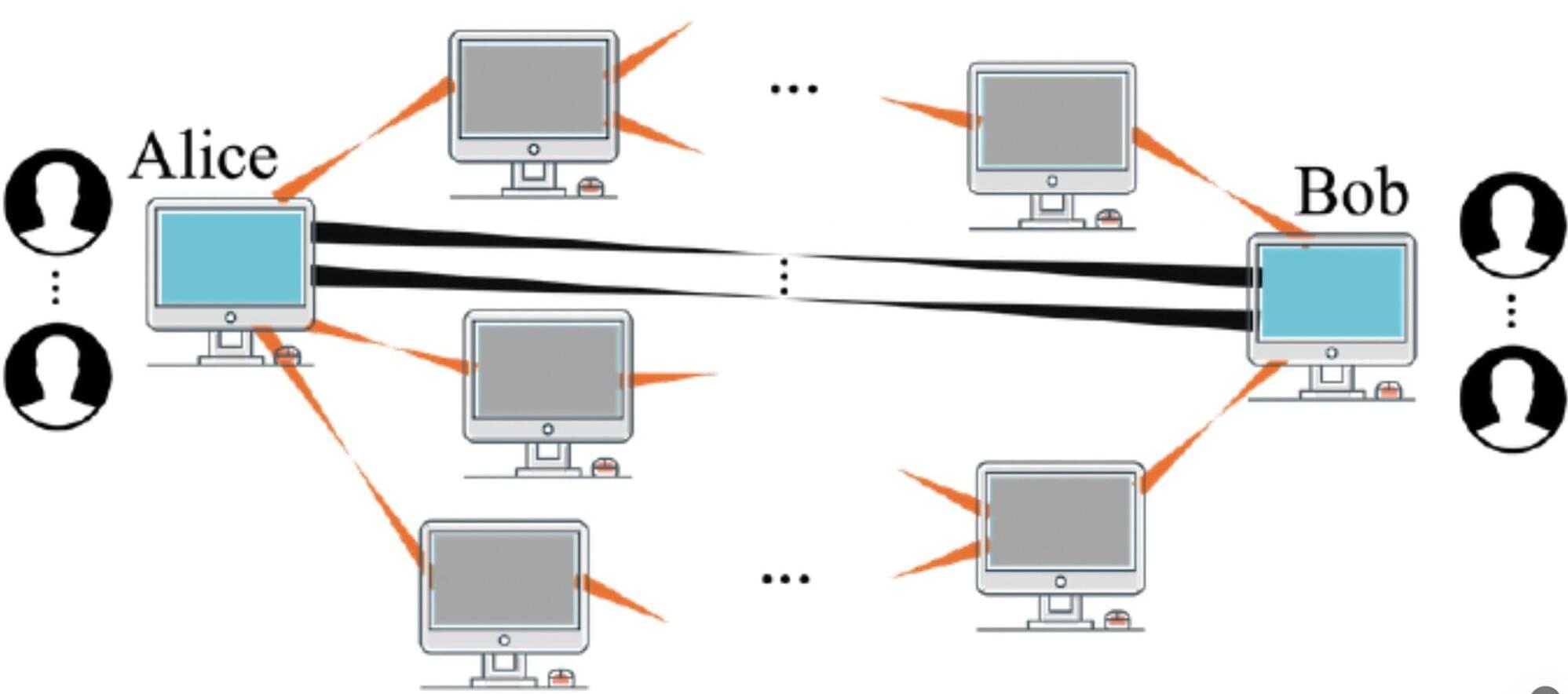

Quantum technologies, systems that process, transfer or store information leveraging quantum mechanical effects, could tackle some real-world problems faster and more effectively than their classical counterparts. In recent years, some engineers have been focusing their efforts on the development of quantum communication systems, which could eventually enable the creation of a “quantum internet” (i.e., an equivalent of the internet in which information is shared via quantum physical effects).

Networks of quantum devices are typically established leveraging quantum entanglement, a correlation that ensures that the state of one particle or system instantly relates to the state of another distant particle or system. A key assumption in the field of quantum science is that greater entanglement would be linked to more reliable communications.

Researchers at Northwestern University recently published a paper in Physical Review Letters that challenges this assumption, showing that, in some realistic scenarios, more entanglement can adversely impact the quality of communications. Their study could inform efforts aimed at building reliable quantum communication networks, potentially also contributing to the future design of a quantum internet.

Light and matter can remain at separate temperatures even while interacting with each other for long periods, according to new research that could help scale up an emerging quantum computing approach in which photons and atoms play a central role.

In a theoretical study published in Physical Review Letters, a University at Buffalo-led team reports that interacting photons and atoms don’t always rapidly reach thermal equilibrium as expected.

Thermal equilibrium is the process by which interacting particles exchange energy before settling at the same temperature, and it typically happens quickly when trapped light repeatedly interacts with matter. Under the right circumstances, however, physicists found that photons and atoms can instead settle at different—and in some cases opposite—temperatures for extended periods.

Research in the lab of UC Santa Barbara materials professor Stephen Wilson is focused on understanding the fundamental physics behind unusual states of matter and developing materials that can host the kinds of properties needed for quantum functionalities.

In a paper published in Nature Materials, Wilson’s lab group has reported on an innovative way to use a phenomenon referred to as frustration of long-range order in a material system to engineer unconventional magnetic states with potential relevance for quantum technologies.

At the same time, Wilson emphasized, “This is fundamental science aimed at addressing a basic question. It’s meant to probe what physics may be possible for future devices.”

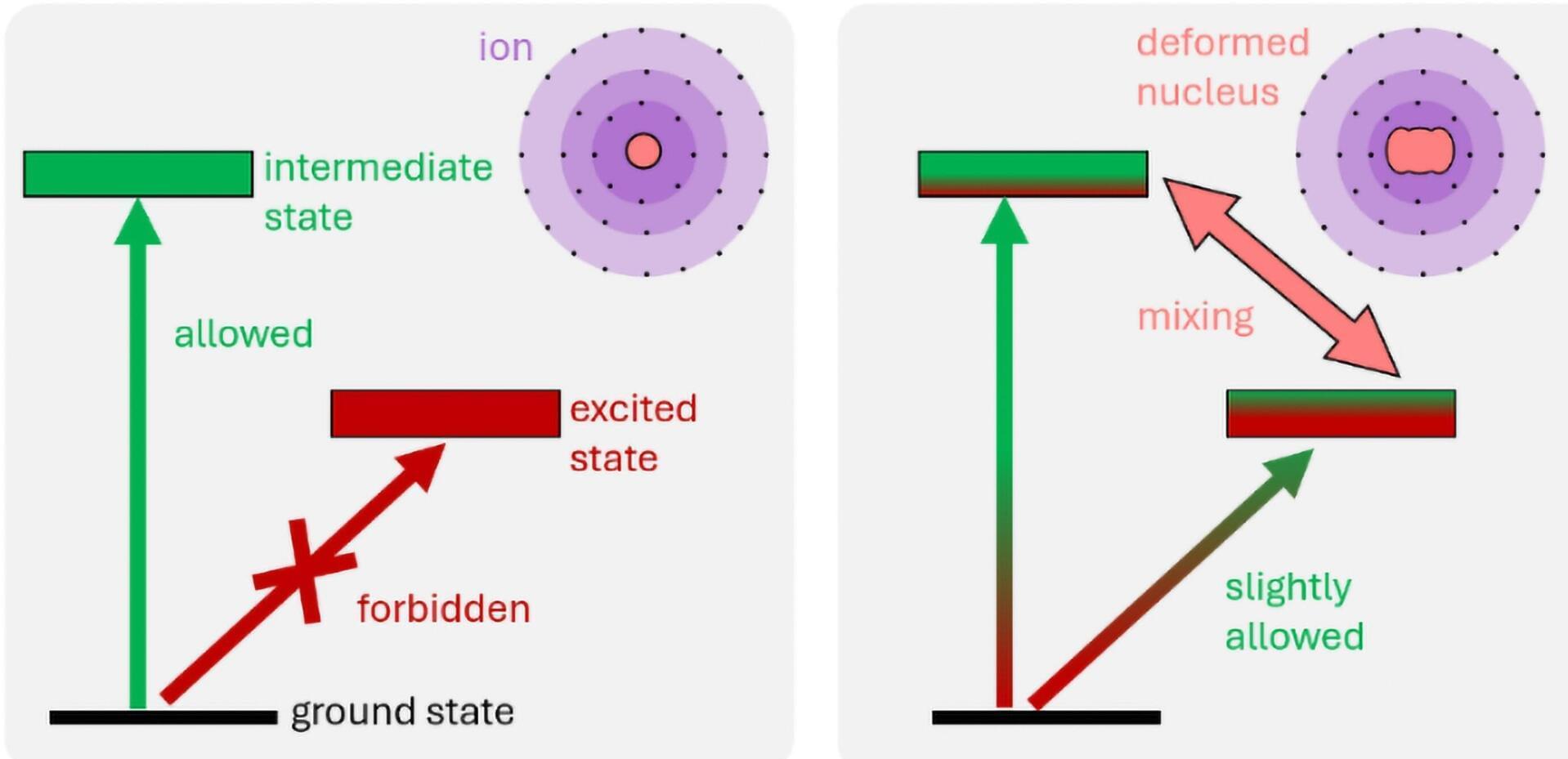

For many years, cesium atomic clocks have been reliably keeping time around the world. But the future belongs to even more accurate clocks: optical atomic clocks. In a few years’ time, they could change the definition of the base unit second in the International System of Units (SI). It is still completely open, which of the various optical clocks will serve as the basis for this.

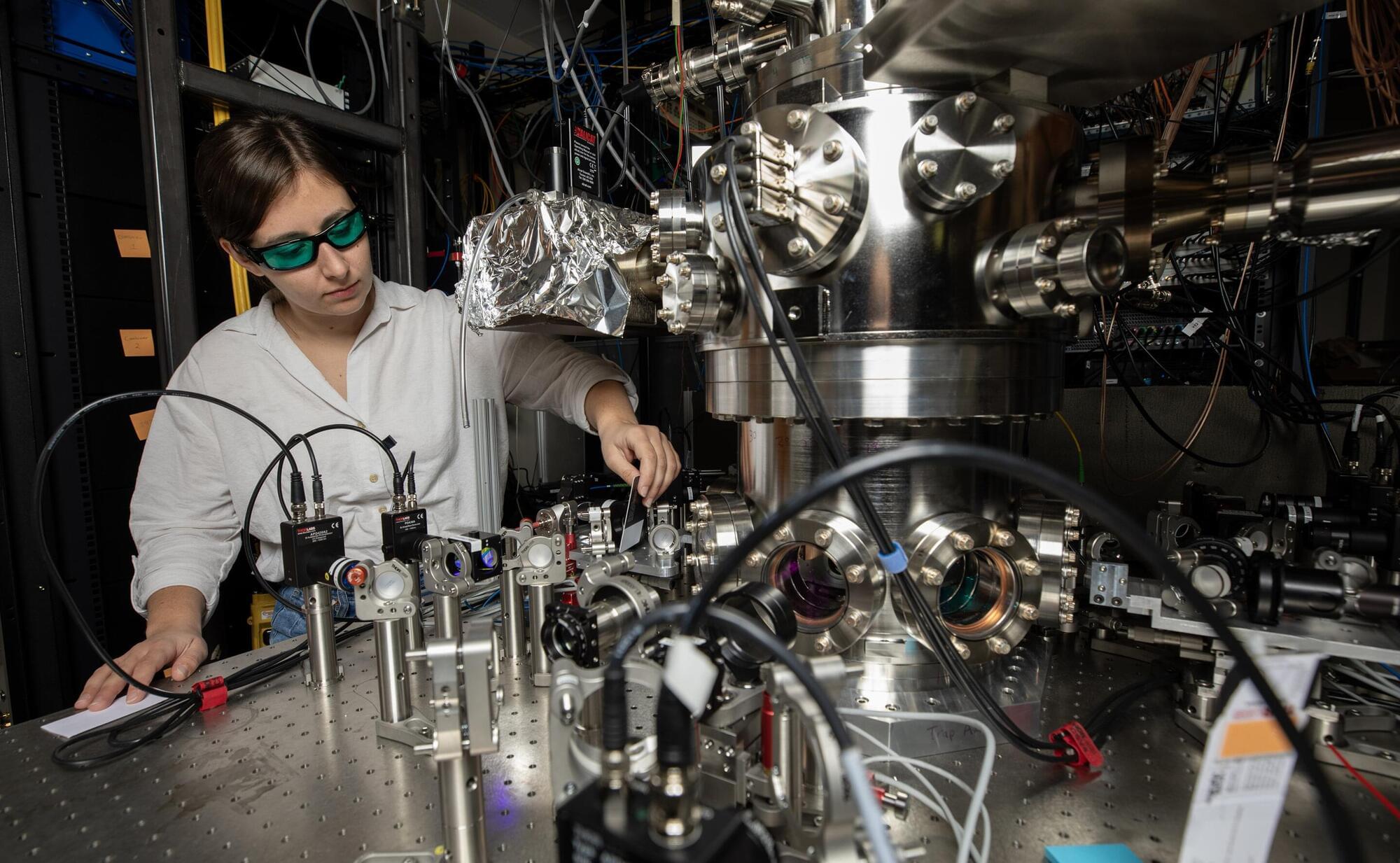

The large number of optical clocks that the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB), as a leading institute in this field, has realized could be joined by another type: an optical multi-ion clock with ytterbium-173 ions. It could combine the high accuracy of individual ions with the improved stability of several ions. This is the result of a cooperation between PTB and the Thai metrology institute NIMT.

The team led by Tanja Mehlstäubler reports on this in the current issue of the journal Physical Review Letters. The results are also interesting for quantum computing and, with a new look inside the atom, for fundamental research.

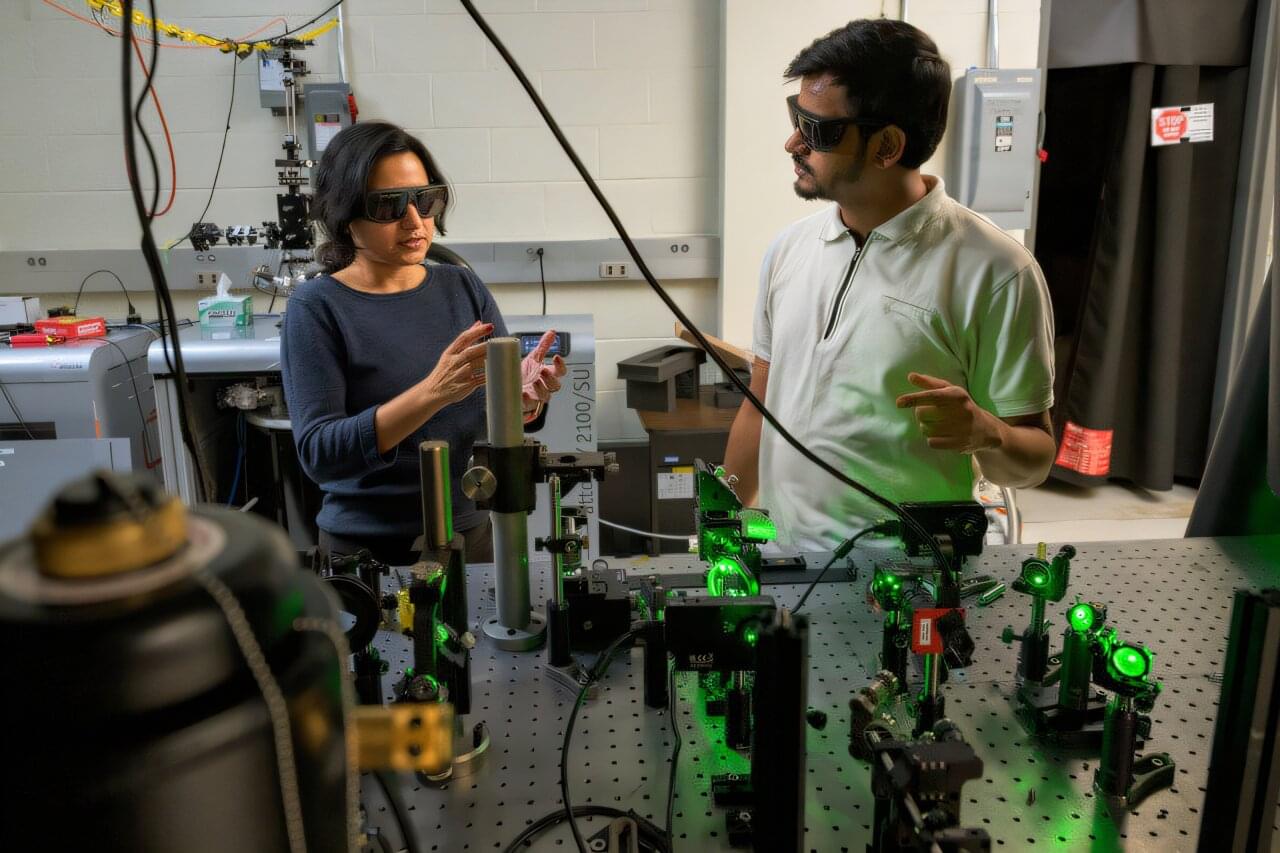

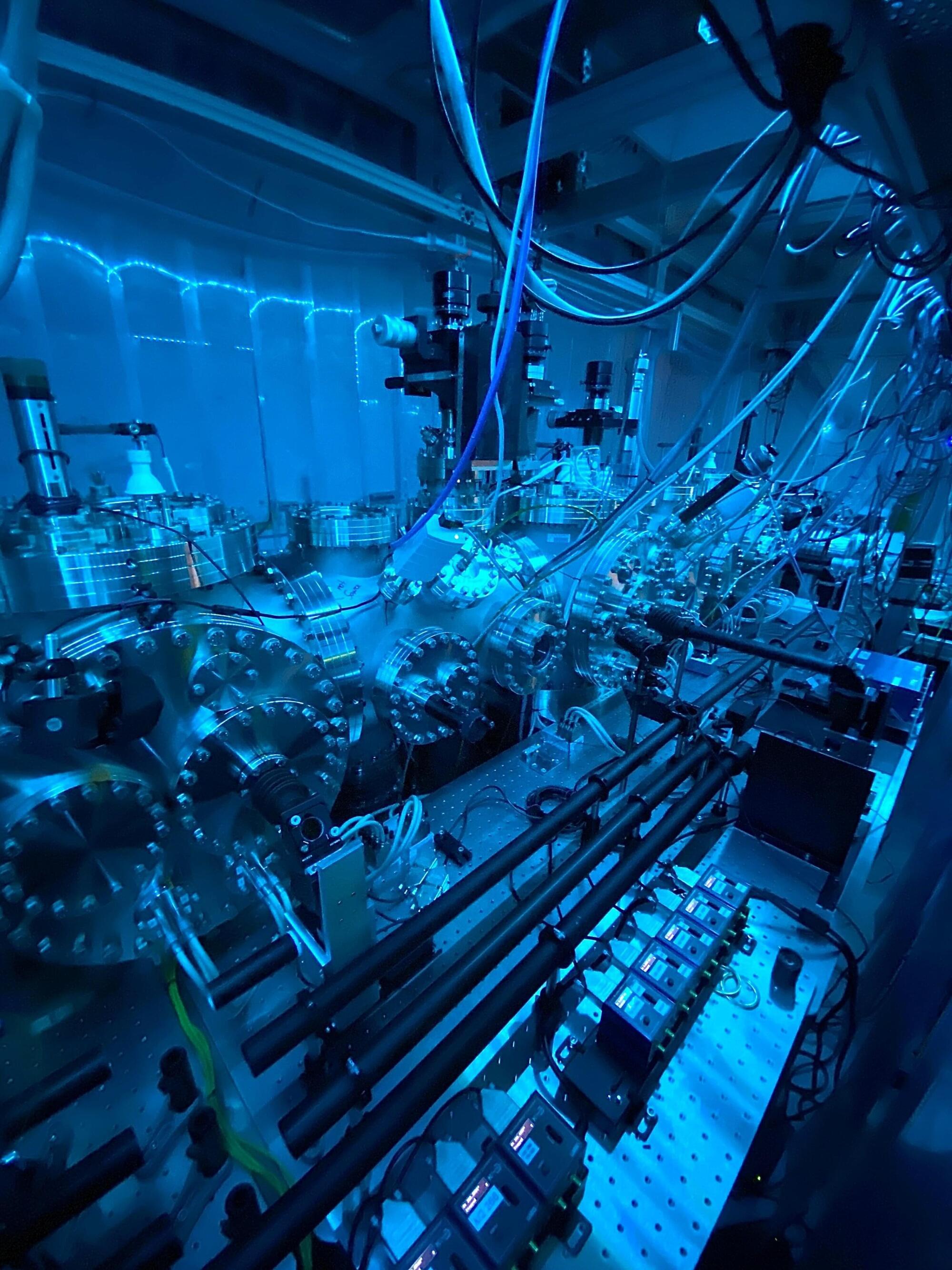

Even very slight environmental noise, such as microscopic vibrations or magnetic field fluctuations a hundred times smaller than Earth’s magnetic field, can be catastrophic for quantum computing experiments with trapped ions.

To address that challenge, researchers at the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) have developed an improved cryogenic vacuum chamber that helps reduce some common noise sources by isolating ions from vibrations and shielding them from magnetic field fluctuations. The new chamber also incorporates an improved imaging system and a radio frequency (RF) coil that can be used to drive ion transitions from within the chamber.

“There’s a lot of excitement around quantum computing today, and trapped ions are just one of the research platforms available, each with their own benefits and drawbacks,” explained Darian Hartsell, a GTRI research scientist who leads the project. “We are trying to mitigate multiple sources of noise in this chamber and make other improvements with one robust new design.”

Imagine computer hardware that is blazing fast and stores more data in less space. That’s the promise of antiferromagnets, magnetic materials that do not interfere with each other and can switch states at high speed, opening the door to advanced computing and quantum applications.

Magnetism comes from unpaired electrons, tiny particles that orbit an atom’s nucleus. Each electron has a property called spin, which can point up or down. In standard ferromagnets, the atomic spins point in the same direction, creating a strong magnetic field. In antiferromagnets, neighboring spins point in opposite directions, canceling each other out and yielding no net magnetism.

Flipping individual spins in an antiferromagnet requires very little movement of magnetization, which allows ultrafast processing. Antiferromagnets can switch states trillions of times per second, compared with billions for ferromagnets. With net zero magnetism, antiferromagnets can be placed very close together without repelling or attracting each other, allowing more data to be stored in a small space.

Can a small lump of metal be in a quantum state that extends over distant locations? A research team at the University of Vienna answers this question with a resounding yes. In the journal Nature, physicists from the University of Vienna and the University of Duisburg-Essen show that even massive nanoparticles consisting of thousands of sodium atoms follow the rules of quantum mechanics. The experiment is currently one of the best tests of quantum mechanics on a macroscopic scale.

In quantum mechanics, not only light but also matter can behave both as a particle and as a wave. This has been proven many times for electrons, atoms, and small molecules through double-slit diffraction or interference experiments. However, we do not see this in everyday life: marbles, stones, and dust particles have a well-defined location and a predictable trajectory; they follow the rules of classical physics.

At the University of Vienna, the team led by Markus Arndt and Stefan Gerlich has now demonstrated for the first time that the wave nature of matter is also preserved in massive metallic nanoparticles. The scale of the particles is impressive: the clusters have a diameter of around 8 nanometers, which is comparable to the size of modern transistor structures.

A quantum state of matter has appeared in a material where physicists thought it would be impossible, forcing a rethink on the conditions that govern the behaviors of electrons in certain materials.

The discovery, made by an international team of researchers, could inform advances in quantum computing, improve electronic efficiencies, and deliver enhanced sensing and imaging technologies.

The state, described as a topological semimetal phase, was theoretically predicted to appear at low temperatures in a material composed of cerium, ruthenium, and tin (CeRu4Sn6), before experiments verified its existence.