#eldddir_earth #eldddir_homo #eldddir_animals.

#eldddir_disaster #eldddir_ocean #eldddir_bombs #eldddir_future #eldddir_tech #eldddir_jupiter #eldddir_mars #eldddir_spacex #eldddir_rockets

#eldddir_earth #eldddir_homo #eldddir_animals.

#eldddir_disaster #eldddir_ocean #eldddir_bombs #eldddir_future #eldddir_tech #eldddir_jupiter #eldddir_mars #eldddir_spacex #eldddir_rockets

Researchers have advanced a decades-old challenge in the field of organic semiconductors, opening new possibilities for the future of electronics. The researchers, led by the University of Cambridge and the Eindhoven University of Technology, have created an organic semiconductor that forces electrons to move in a spiral pattern, which could improve the efficiency of OLED displays in television and smartphone screens, or power next-generation computing technologies such as spintronics and quantum computing.

The semiconductor they developed emits circularly polarized light—meaning the light carries information about the ‘handedness’ of electrons. The internal structure of most inorganic semiconductors, like silicon, is symmetrical, meaning electrons move through them without any preferred direction.

However, in nature, molecules often have a chiral (left-or right-handed) structure: like human hands, chiral molecules are mirror images of one another. Chirality plays an important role in biological processes like DNA formation, but it is a difficult phenomenon to harness and control in electronics.

Physics has a problem—their key models of quantum theory and the theory of relativity do not fit together. Now, Dr. Wolfgang Wieland from Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU) is developing an approach that reconciles the two theories in a problematic area. A recently published paper that was published in Classical and Quantum Gravity gives hope that this could work.

There are four fundamental forces in the universe: gravity, electromagnetism, the weak and the strong interaction. While general relativity describes gravity, quantum theory deals with the other three forces. This creates a problem: “As early as the 1930s, it was recognized that the two theories do not fit together,” explains Dr. Wieland, who leads a Heisenberg project on this topic at the Chair of Quantum Gravity at FAU.

Usually, this has no major consequences: general relativity is mainly used to calculate the behavior of large masses in the universe. Quantum theory, on the other hand, focuses on the world of the very smallest things. However, to better understand key phenomena such as the Big Bang or black holes, a model is needed that unites both concepts—quantum gravity. General relativity states that all matter in a black hole is united at one tiny point. It is therefore important to understand how gigantic gravitational forces act in the microcosm, although this is where the laws of quantum mechanics actually apply.

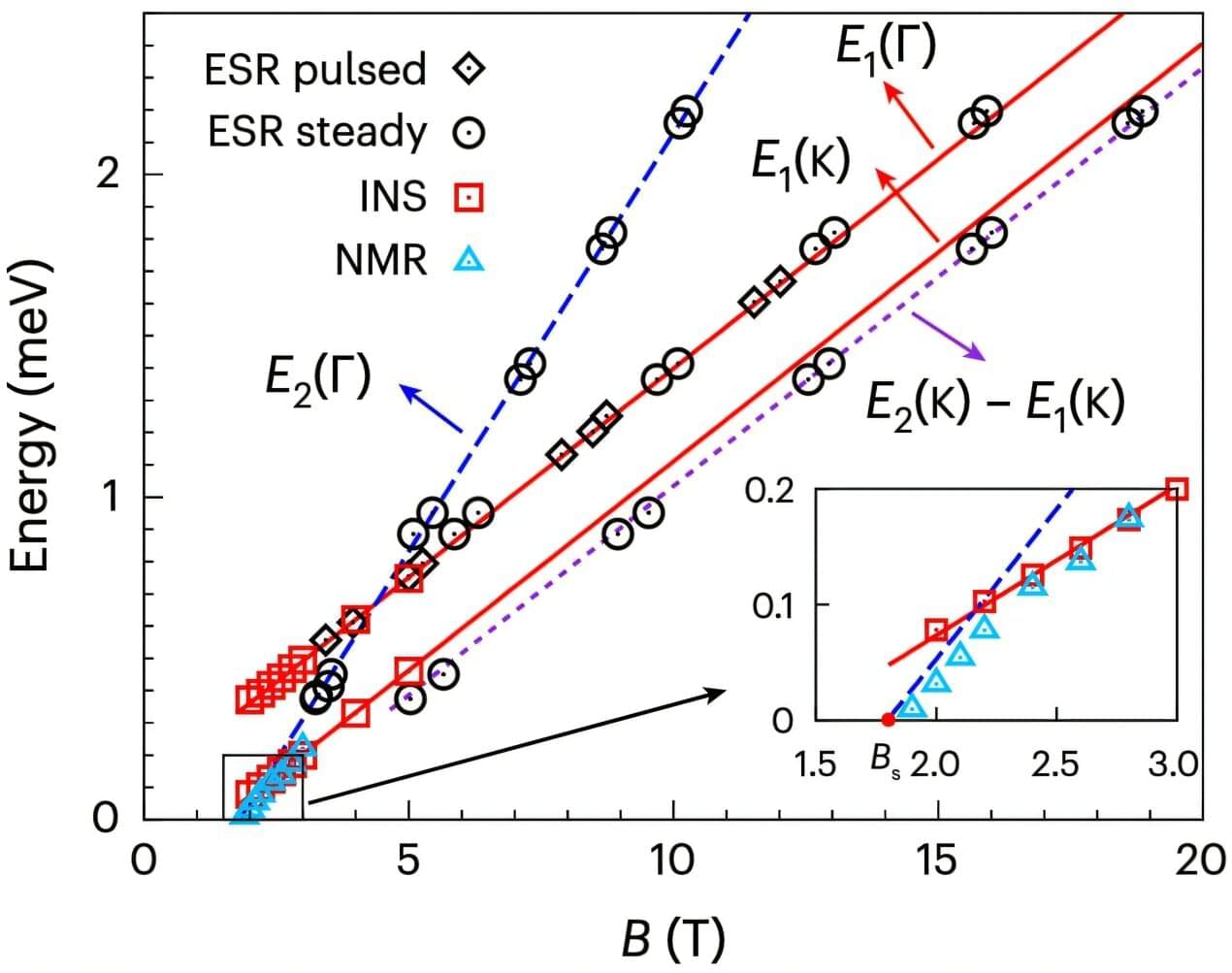

Using the Multi-frequency High Field Electron Spin Resonance Spectrometer at the Steady-State High Magnetic Field Facility (SHMFF), researchers observed the first-ever Bose–Einstein condensation (BEC) of a two-magnon bound state in a magnetic material. The facility is in the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and includes a research team from Southern University of Science and Technology, Zhejiang University, Renmin University of China, and the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organization.

This discovery was published in Nature Materials.

BEC is a fascinating quantum phenomenon where particles, typically bosons, condense into a single collective state at ultra-low temperatures. While this effect has been seen in cold atoms, it had never been observed in a magnetic system until now.

Researchers at the University of Adelaide have performed the first imaging of embryos using cameras designed for quantum measurements.

The University’s Center of Light for Life academics investigated how to best use ultrasensitive camera technology, including the latest generation of cameras that can count individual packets of light energy at each pixel, for life sciences.

Center director Professor Kishan Dholakia said the sensitive detection of these packets of light energy, termed photons, is vitally important for capturing biological processes in their natural state—allowing researchers to illuminate live cells with gentle doses of light.

For decades, scientists believed that lead-208, a “doubly magic” and highly stable atomic nucleus, was perfectly spherical. However, groundbreaking new research has shattered this assumption, revealing that its nucleus is actually elongated, much like a rugby ball.

By using an advanced gamma-ray spectrometer and high-speed particle collisions, researchers uncovered unexpected quantum behavior that contradicts long-standing nuclear theory. This revelation forces physicists to rethink fundamental principles of nuclear structure, potentially reshaping our understanding of heavy elements and their formation in the universe.

Lead-208: A Surprising Discovery

A major breakthrough in organic semiconductors.

Semiconductors are materials with electrical conductivity that falls between conductors and insulators, making them essential for modern electronics. They are typically crystalline solids, the most common of which is silicon, used extensively in the production of electronic components such as transistors and diodes. Semiconductors are unique because their conductivity can be altered and controlled through doping—adding impurities to the material to change its electrical properties. This property allows them to serve as the foundation for integrated circuits and microchips, powering everything from computers and smartphones to advanced medical devices and renewable energy technologies. The behavior of semiconductors is also crucial in the development of various electronic, photonic, and quantum devices.

Quantum systems hold the promise of tackling some complex problems faster and more efficiently than classical computers. Despite their potential, so far only a limited number of studies have conclusively demonstrated that quantum computers can outperform classical computers on specific tasks. Most of these studies focused on tasks that involve advanced computations, simulations or optimization, which can be difficult for non-experts to grasp.

Researchers at the University of Oxford and the University of Sevilla recently demonstrated a quantum advantage over a classical scenario on a cooperation task called the odd-cycle game. Their paper, published in Physical Review Letters, shows that a team with quantum entanglement can win this game more often than a team without.

“There is a lot of talk about quantum advantage and how quantum systems will revolutionize entire industries, but if you look closely, in many cases, there is no mathematical proof that classical methods definitely cannot find solutions as efficiently as quantum algorithms,” Peter Drmota, first author of the paper, told Phys.org.

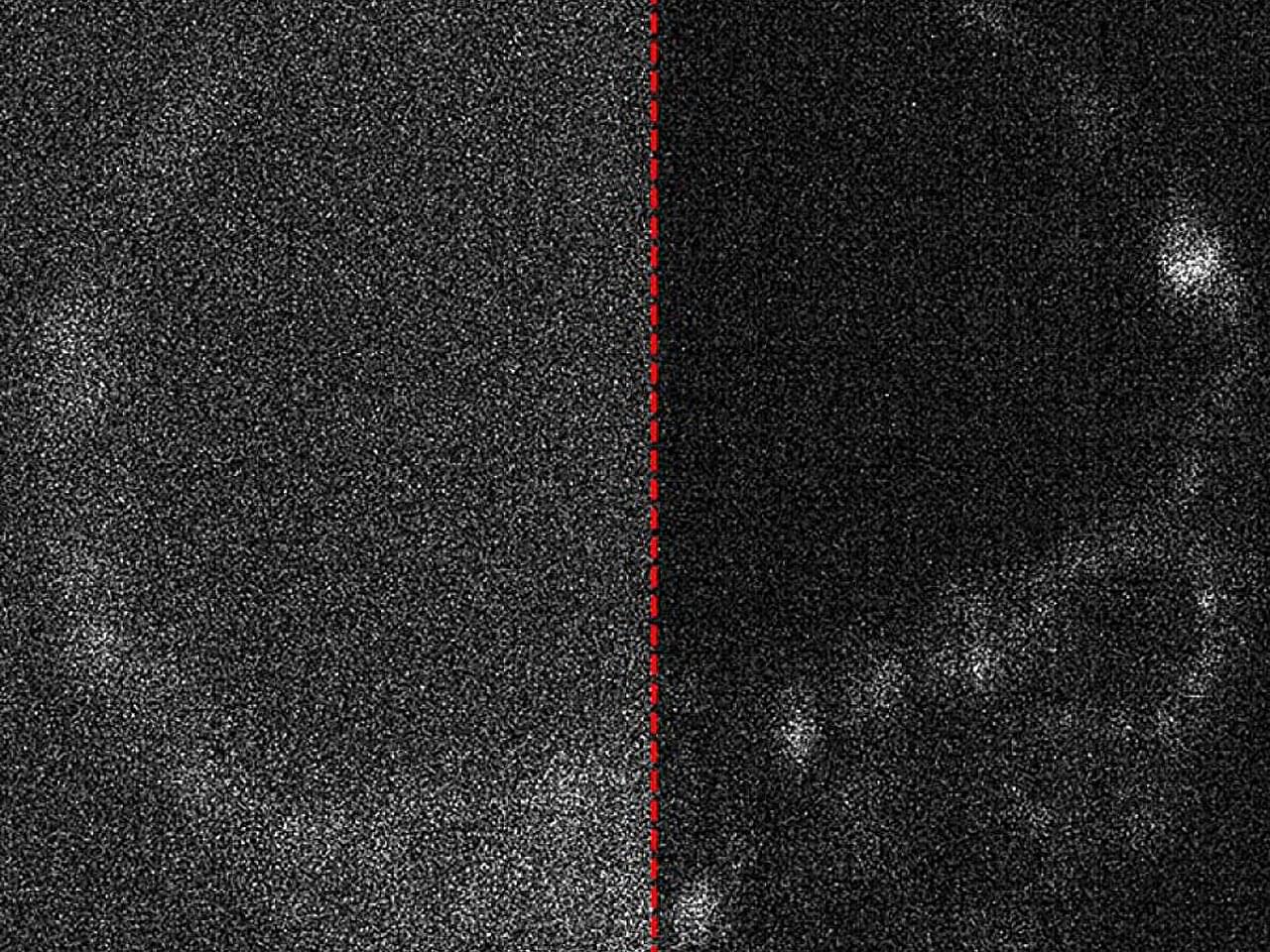

In a recent collaboration between the High Magnetic Field Center of the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science of Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the University of Science and Technology of China, researchers introduced the concept of the topological Kerr effect (TKE) by utilizing the low-temperature magnetic field microscopy system and magnetic force microscopy imaging system supported by the steady-state high magnetic field experimental facility.

The findings, published in Nature Physics, hold significant promise for advancing our understanding of topological magnetic structures.

Originating in particle physics, skyrmions represent unique topological excitations found in condensed matter magnetic materials. These structures, characterized by their vortex or ring-like arrangement of spins, possess non-trivial properties that make them potential candidates for next-generation magnetic storage and logic devices.

The Korea Research Institute of Standards and Science (KRISS) has developed a technology that controls the energy of single electrons in the desired form. This technology reduces the instability of electrons caused by external environments and enables stable quantum state implementation, making it a foundational technology to enhance the performance of single-electron qubits.

The research was conducted in collaboration with Jeonbuk National University, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), and Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST), and the results were published in Nano Letters.

Electrons are fundamental particles that make up atoms, and when their paths are divided, they exhibit the quantum superposition phenomenon, passing through both paths (0 and 1) simultaneously.