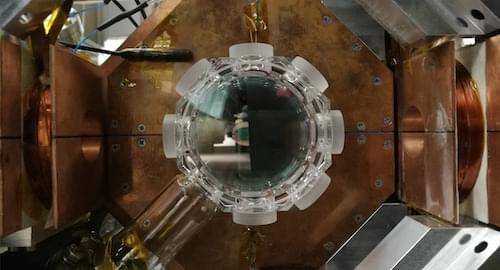

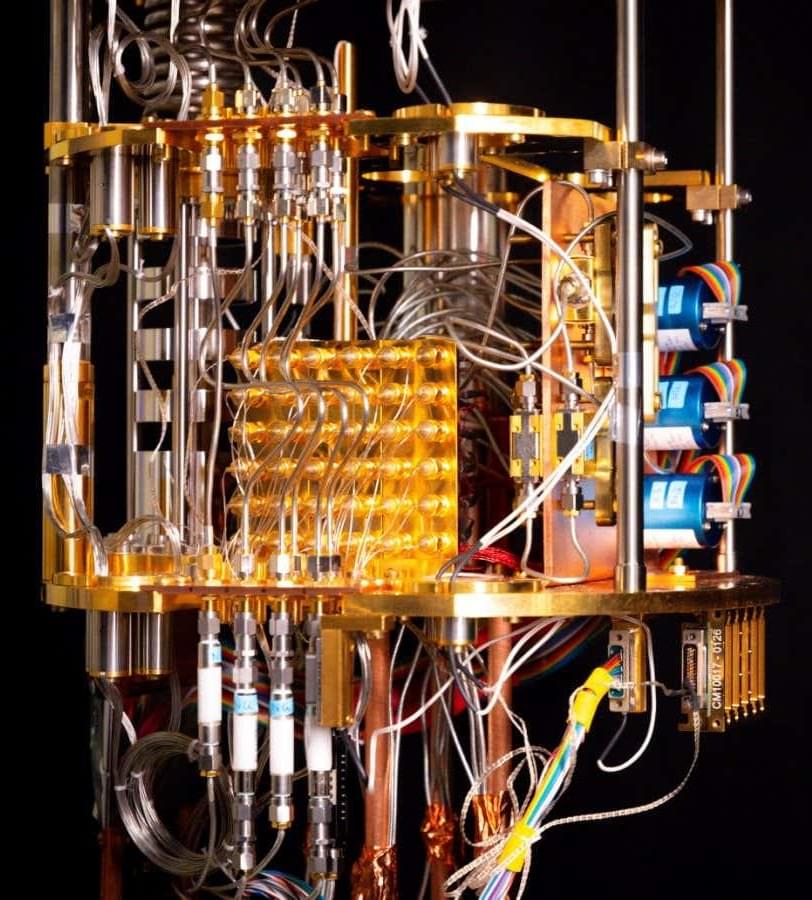

Researchers have generated Bose-Einstein condensates with a repetition rate exceeding 2 Hz, a feat that could increase the bandwidth of quantum sensors.

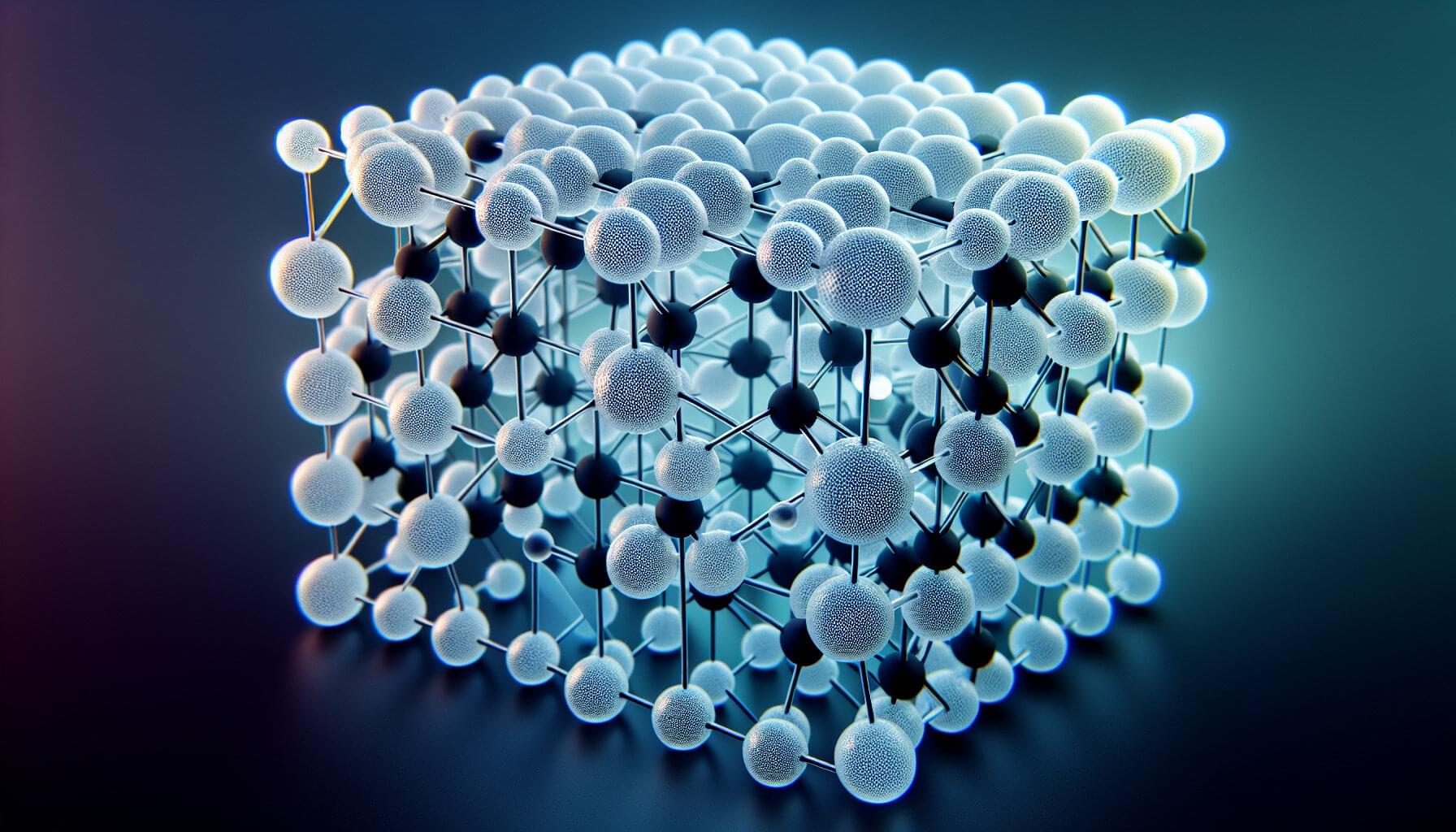

In a variety of technological applications related to chemical energy generation and storage, atoms and molecules diffuse and react on metallic surfaces. Being able to simulate and predict this motion is crucial to understanding material degradation, chemical selectivity, and to optimizing the conditions of catalytic reactions. Central to this is a correct description of the constituent parts of atoms: electrons and nuclei.

An electron is incredibly light—its mass is almost 2,000 times smaller than that of even the lightest nucleus. This mass disparity allows electrons to adapt rapidly to changes in nuclear positions, which usually enables researchers to use a simplified “adiabatic” description of atomic motion.

While this can be an excellent approximation, in some cases the electrons are affected by nuclear motion to such an extent that we need to abandon this simplification and account for the coupling between the dynamics of electrons and nuclei, leading to so-called “non-adiabatic effects.”

Resonantly tunable quantum cascade lasers (QCLs) are high-performance laser light sources for a wide range of spectroscopy applications in the mid-infrared (MIR) range. Their high brilliance enables minimal measurement times for more precise and efficient characterization processes and can be used, for example, in chemical and pharmaceutical industries, medicine or security technology. Until now, however, the production of QCL modules has been relatively complex and expensive.

The Fraunhofer Institute for Applied Solid State Physics IAF has therefore developed a semi-automated process that significantly simplifies the production of QCL modules with a MOEMS (micro-opto-electro-mechanical system) grating scanner in an external optical cavity (EC), making it more cost-efficient and attractive for industry. The MOEMS-EC-QCL technology was developed by Fraunhofer IAF in collaboration with the Fraunhofer Institute for Photonic Microsystems IPMS.

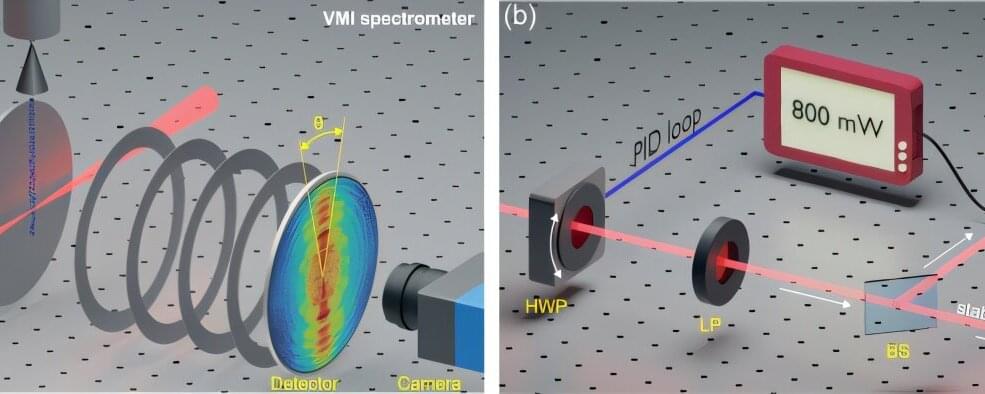

Tunneling is a peculiar quantum phenomenon with no classical counterpart. It plays an essential role for strong field phenomena in atoms and molecules interacting with intense lasers. Processes such as high-order harmonic generation are driven by electron dynamics following tunnel ionization.

While this has been widely explored, the behavior of electrons under the tunneling barrier, though equally significant, has remained obscure. The understanding of laser-induced strong field ionization distinguishes two scenarios for a given system and laser frequency: the multiphoton regime at rather low intensities and tunneling at high intensities.

However, most strong-field experiments have been carried out in an intermediate situation where multiphoton signatures are observed while tunneling is still the dominant process.

Wormholes are a popular feature in science fiction, the means through which spacecraft can achieve faster-than-light (FTL) travel and instantaneously move from one point in spacetime to another. And while the General Theory of Relativity forbids the existence of “traversable wormholes,” recent research has shown that they are actually possible within the domain of quantum physics.