In physics, entropy is the process of a system losing energy and dissolving into chaos. This applies to social systems in everyday life, too. Limiting energy loss can make social systems run better.

What is the origin of black holes and how is that question connected with another mystery, the nature of dark matter? Dark matter comprises the majority of matter in the Universe, but its nature remains unknown.

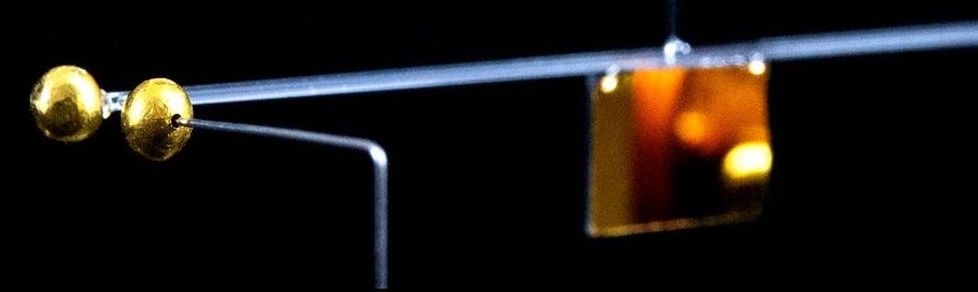

Multiple gravitational wave detections of merging black holes have been identified within the last few years by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), commemorated with the 2017 physics Nobel Prize to Kip Thorne, Barry Barish, and Rainer Weiss. A definitive confirmation of the existence of black holes was celebrated with the 2020 physics Nobel Prize awarded to Andrea Ghez, Reinhard Genzel and Roger Penrose. Understanding the origin of black holes has thus emerged as a central issue in physics.

Surprisingly, LIGO has recently observed a 2.6 solar-mass black hole candidate (event GW190814, reported in Astrophysical Journal Letters 896 (2020) 2, L44). Assuming this is a black hole, and not an unusually massive neutron star, where does it come from?

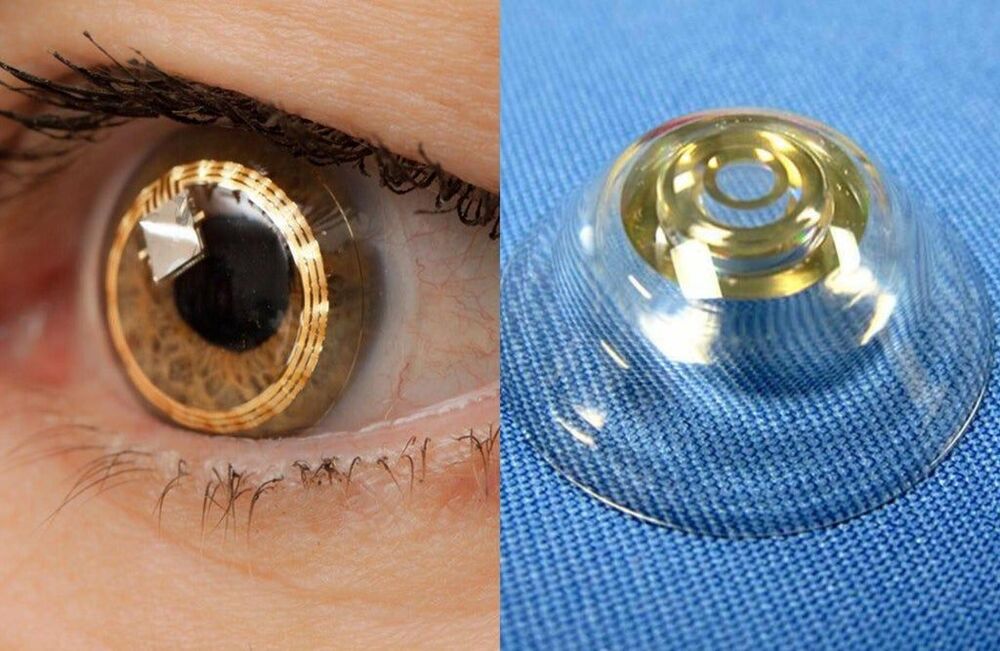

Holograms deliver an exceptional representation of 3D world around us. Plus, they’re beautiful. (Go ahead — check out the holographic dove on your Visa card.) Holograms offer a shifting perspective based on the viewer’s position, and they allow the eye to adjust focal depth to alternately focus on foreground and background.

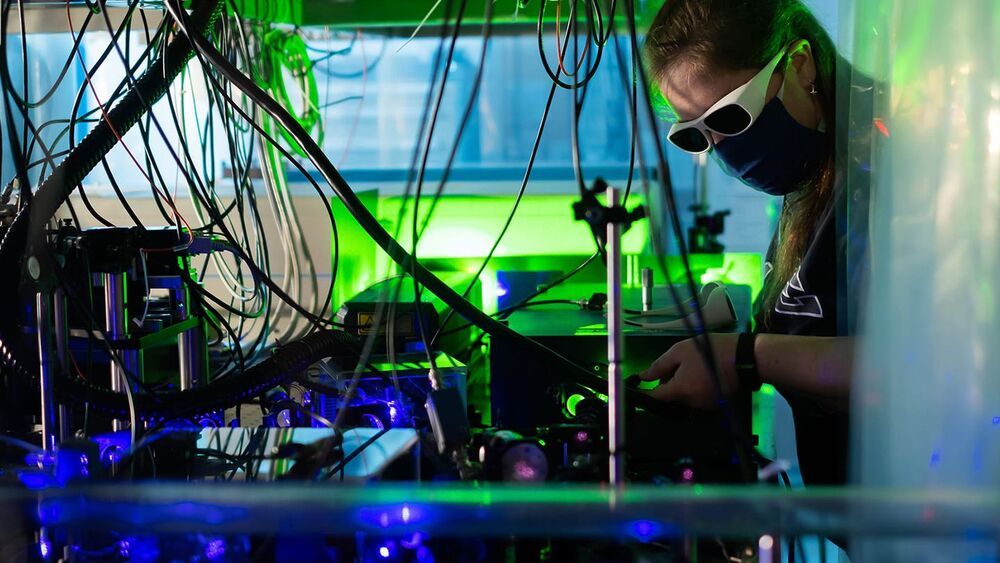

Researchers have long sought to make computer-generated holograms, but the process has traditionally required a supercomputer to churn through physics simulations, which is time-consuming and can yield less-than-photorealistic results. Now, MIT researchers have developed a new way to produce holograms almost instantly — and the deep learning-based method is so efficient that it can run on a laptop in the blink of an eye, the researchers say.

Scientists have taken a major step forward in harnessing machine learning to accelerate the design for better batteries: Instead of using it just to speed up scientific analysis by looking for patterns in data, as researchers generally do, they combined it with knowledge gained from experiments and equations guided by physics to discover and explain a process that shortens the lifetimes of fast-charging lithium-ion batteries.

It was the first time this approach, known as “scientific machine learning,” has been applied to battery cycling, said Will Chueh, an associate professor at Stanford University and investigator with the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory who led the study. He said the results overturn long-held assumptions about how lithium-ion batteries charge and discharge and give researchers a new set of rules for engineering longer-lasting batteries.

The research, reported today in Nature Materials, is the latest result from a collaboration between Stanford, SLAC, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Toyota Research Institute (TRI). The goal is to bring together foundational research and industry know-how to develop a long-lived electric vehicle battery that can be charged in 10 minutes.

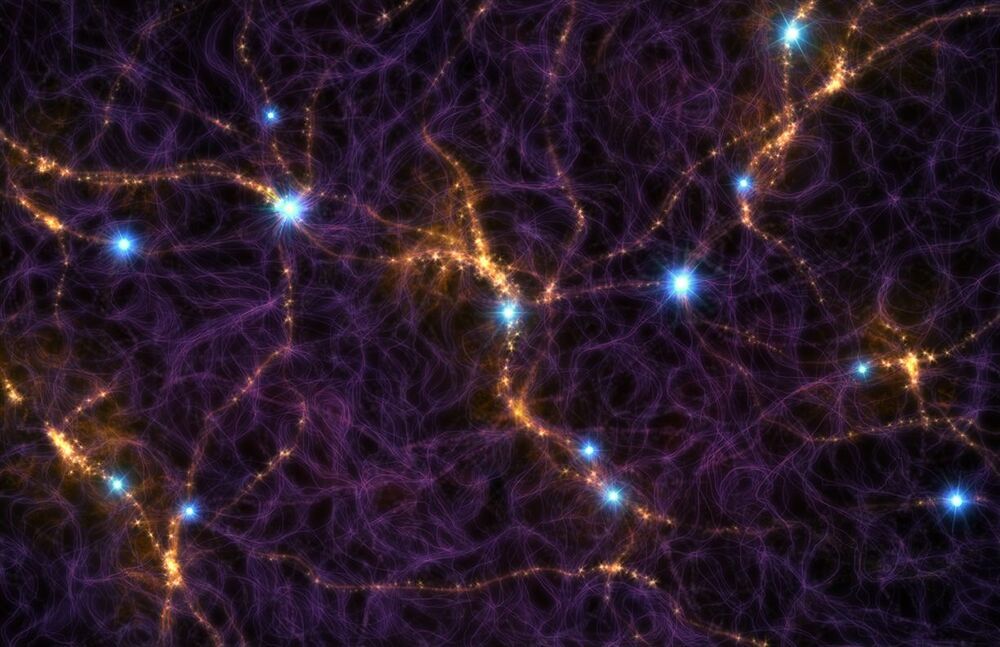

How can you possibly use simulations to reconstruct the history of the entire universe using only a small sample of galaxy observations? Through big data, that’s how.

Theoretically, we understand a lot of the physics of the history and evolution of the universe. We know that the universe used to be a lot smaller, denser, and hotter in the past. We know that its expansion is accelerating today. We know that the universe is made of very different things, including galaxies (which we can see) and dark matter (which we can’t).

We know that the largest structures in the universe have evolved slowly over time, starting as just small seeds and building up over billions of years through gravitational attraction.

Astronomers have detected the best place and time to live in the Milky Way, in a recent study published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

More than six billion years ago, the outskirts of the Milky Way were the safest places for the development of possible life forms, sheltered from the most violent explosions in the universe, that is, the gamma-ray bursts and supernovae.

Also read: Astronomers discover new exoplanet instrumental in hunt for traces of life beyond solar system.