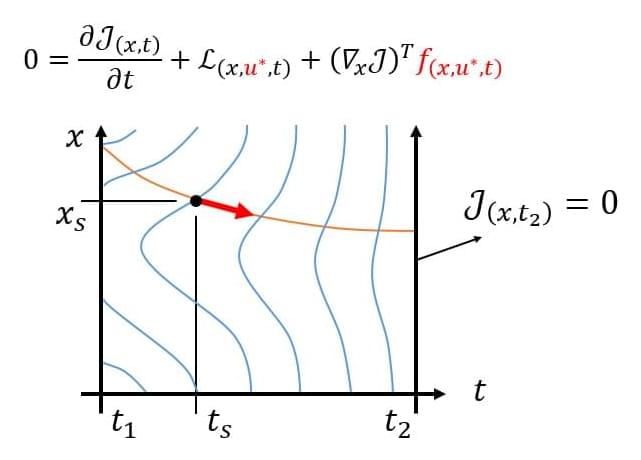

A Dynamic Programming approach.

We also point out an observation that will be the topic of this post. Classic dynamics system is a solution of an optimal control problem.

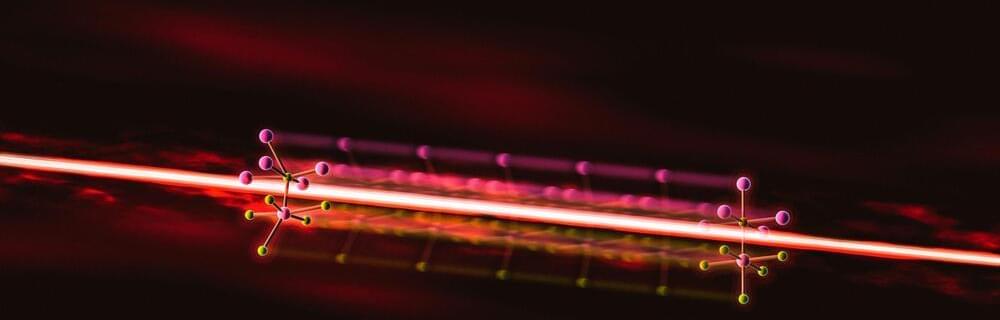

X-ray laser experiments show that intense light distorts the structure of a thermoelectric material in a unique way, opening a new avenue for controlling the properties of materials.

Thermoelectric materials convert heat to electricity and vice versa, and their atomic structures are closely related to how well they perform.

Now researchers have discovered how to change the atomic structure of a highly efficient thermoelectric material, tin selenide, with intense pulses of laser light. This result opens a new way to improve thermoelectrics and a host of other materials by controlling their structure, creating materials with dramatic new properties that may not exist in nature.

Physicists have discovered a new way to coat soft robots in materials that allow them to move and function in a more purposeful way. The research, led by the University of Bath, is described in a paper published on March 11, 2022, in Science Advances.

Authors of the study believe their breakthrough modeling on ‘active matter’ could mark a turning point in the design of robots. With further development of the concept, it may be possible to determine the shape, movement, and behavior of a soft solid not by its natural elasticity but by human-controlled activity on its surface.

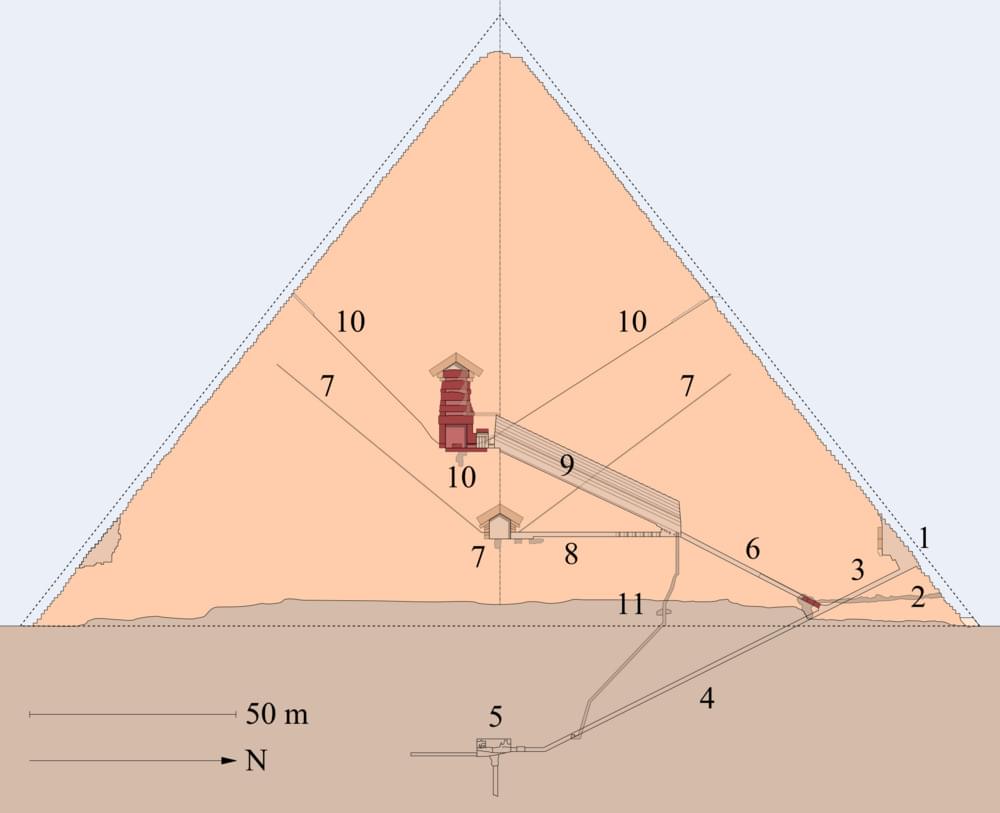

The Great Pyramid of Giza might be the most iconic structure humans ever built. Ancient civilizations constructed archaeological icons that are a testament to their greatness and persistence. But in some respects, the Great Pyramid stands alone. Of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, only the Great Pyramid stands relatively intact.

A team of scientists will use advances in High Energy Physics (HIP) to scan the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza with cosmic-ray muons. They want to see deeper into the Great Pyramid than ever before and map its internal structure. The effort is called the Explore the Great Pyramid (EGP) mission.

The Great Pyramid of Giza has stood since the 26th century BC. It’s the tomb of the Pharoah Khufu, also known as Cheops. Construction took about 27 years, and it was built with about 2.3 million blocks of stone—a combination of limestone and granite—weighing in at about 6 million tons. For over 3,800 years, it was the tallest human-made structure in the world. We see now only the underlying core structure of the Great Pyramid. The smooth white limestone casing was removed over time.

Check Out Subcultured’s Anime Episode on PBS Voices: https://youtu.be/oSCj8H4TGTo.

PBS Member Stations rely on viewers like you. To support your local station, go to: http://to.pbs.org/DonateSPACE

If you’ve studied any physics you know that like charges repel and opposite charges attract. But why? It’s as though this thing — electric charge — is as fundamental a property of an object as its mass. It just sort of… is. Well it turns out if you dig deep enough, the fundamental-ness of charge unravels, and in many things, including mass itself, are unraveled with it.

Sign Up on Patreon to get access to the Space Time Discord!

https://www.patreon.com/pbsspacetime.

Check out the Space Time Merch Store.

https://www.pbsspacetime.com/shop.

Sign up for the mailing list to get episode notifications and hear special announcements!

Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity profoundly changed our thinking about fundamental concepts in physics, such as space and time. But it also left us with some deep mysteries. One was black holes, which were only unequivocally detected over the past few years. Another was “wormholes” – bridges connecting different points in spacetime, in theory providing shortcuts for space travellers.

Wormholes are still in the realm of the imagination. But some scientists think we will soon be able to find them, too. Over the past few months, several new studies have suggested intriguing ways forward.

Black holes and wormholes are special types of solutions to Einstein’s equations, arising when the structure of spacetime is strongly bent by gravity. For example, when matter is extremely dense, the fabric of spacetime can become so curved that not even light can escape. This is a black hole.

This video covers the world in 2,300 and its future technologies. Watch this next video about the world in 2200: https://bit.ly/3htaWEr.

► BlockFi: Get Up To $250 In Bitcoin: https://bit.ly/3rPOf1V

► M1 Finance: Open A Roth IRA And Get Up To $500: https://bit.ly/3KHZvq0

► Jarvis AI: Write 5x Faster With Artificial Intelligence: https://bit.ly/3HbfvhO

► SurfShark: Secure Your Digital Life (83% Off): https://surfshark.deals/BUSINESSTECH

► Udacity: 75% Off All Courses (Biggest Discount Ever): https://bit.ly/3j9pIRZ

► Brilliant: Learn Science And Math Interactively (20% Off): https://bit.ly/3HAznLL

► Business Ideas Academy: Start A Business You Love: https://bit.ly/3KI7B1S

SOURCES:

• https://www.futuretimeline.net.

• The Future of Humanity (Michio Kaku): https://amzn.to/3Gz8ffA

• The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology (Ray Kurzweil): https://amzn.to/3ftOhXI

• Physics of the Future (Michio Kaku): https://amzn.to/33NP7f7

• https://science.howstuffworks.com/science-vs-myth/everyday-m…tation.htm.

Patreon Page: https://www.patreon.com/futurebusinesstech.

Official Discord Server: https://discord.gg/R8cYEWpCzK

💡 On this channel, I explain the following concepts:

• Future and emerging technologies.

• Future and emerging trends related to technology.

• The connection between Science Fiction concepts and reality.

SUBSCRIBE: https://bit.ly/3geLDGO

Disclaimer:

Black holes are among the most compelling mysteries of the universe. Nothing, not even light, can escape a black hole. And at the center of nearly every galaxy there is a supermassive black hole that’s millions to billions of times more massive than the sun. Understanding black holes, and how they become supermassive, could shed light on the evolution of the universe.

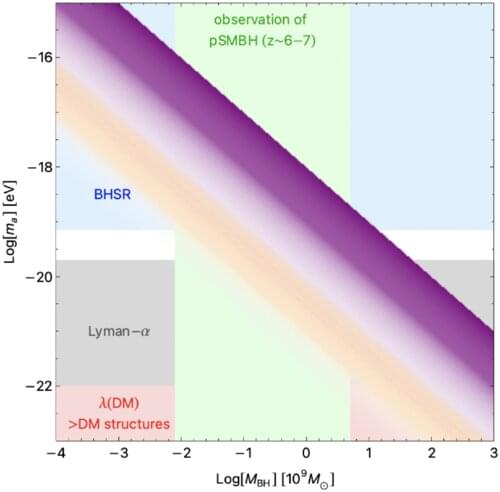

Three physicists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory have recently developed a model to explain the formation of supermassive black holes, as well as the nature of another phenomenon: dark matter. In a paper published in Physical Review Letters, theoretical physicists Hooman Davoudiasl, Peter Denton, and Julia Gehrlein describe a cosmological phase transition that facilitated the formation of supermassive black holes in a dark sector of the universe.

A cosmological phase transition is akin to a more familiar type of phase transition: bringing water to a boil. When water reaches the exact right temperature, it erupts into bubbles and vapor. Imagine that process taking place with a primordial state of matter. Then, shift the process in reverse so it has a cooling effect and magnify it to the scale of the universe.