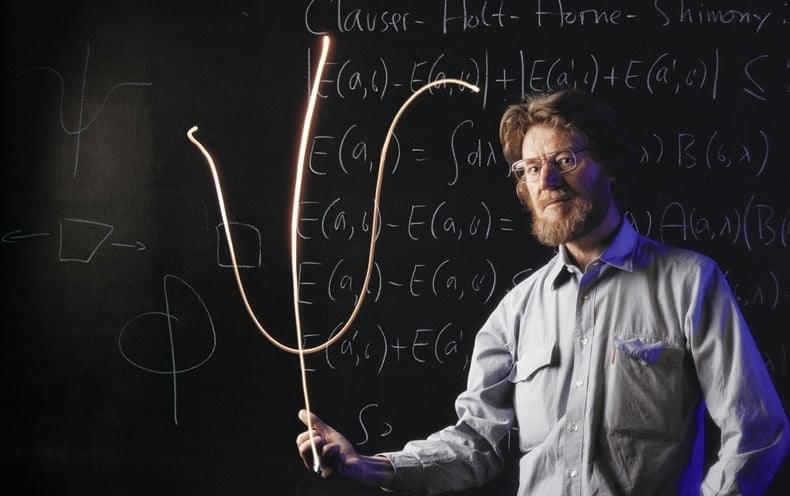

Elegant experiments with entangled light have laid bare a profound mystery at the heart of reality.

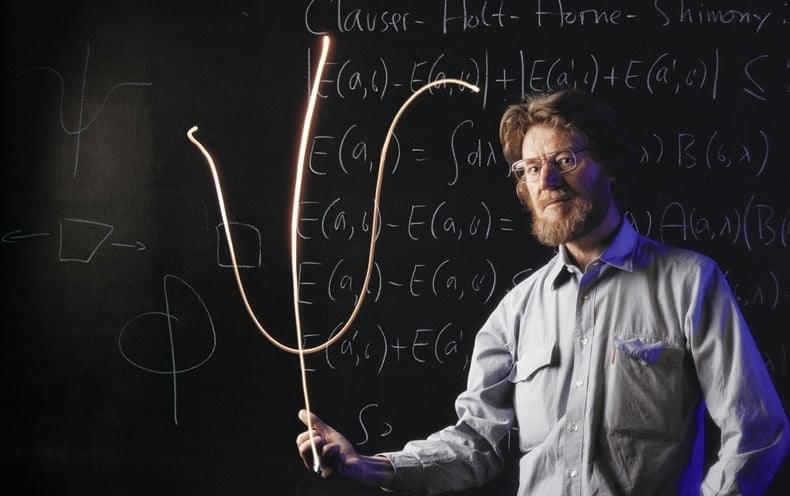

That’s because as a white dwarf draws material away from its hydrogen-burning partner, the stolen gas follows the star’s magnetic field lines in a big, curving arc toward its new home. And in the process, it drains energy from the stars’ whirling dance (so do the gravitational waves produced by their rotation). When that happens, both stars fall toward the shared center of gravity they’re orbiting. Closer orbits also mean shorter orbits, so it takes the stars less time to complete a single lap.

And the closer the stars get, the stronger the gravitational waves they produce, which drains away more energy, so they fall even closer together. By the time they’re close enough to complete an orbit in just a handful of minutes, the donor star has usually run out of hydrogen. That’s why the really close, fast-orbiting cataclysmic binaries tend to be a white dwarf and a helium-burning star.

This is perhaps the strangest thing about the arrow of time: “It only lasts for a little while,” says Carroll.

It’s very hard to picture what might happen if the arrow of time eventually vanishes. “When we think we produce heat in our neurons,” says Rovelli. “Thinking is a process in which the neuron needs entropy to work. Our sense of time passing is just what entropy does to our brain.”

The arrow of time that arises from entropy brings us a long way closer to understanding why time only goes forward. But there may be more arrows of time than this one – in fact there is arguably an entire volley of arrows of time pointing from the past to the future. To understand these, we have to step from physics into philosophy.

Deep generative models are a popular data generation strategy used to generate high-quality samples in pictures, text, and audio and improve semi-supervised learning, domain generalization, and imitation learning. Current deep generative models, however, have shortcomings such as unstable training objectives (GANs) and low sample quality (VAEs, normalizing flows). Although recent developments in diffusion and scored-based models attain equivalent sample quality to GANs without adversarial training, the stochastic sampling procedure in these models is sluggish. New strategies for securing the training of CNN-based or ViT-based GAN models are presented.

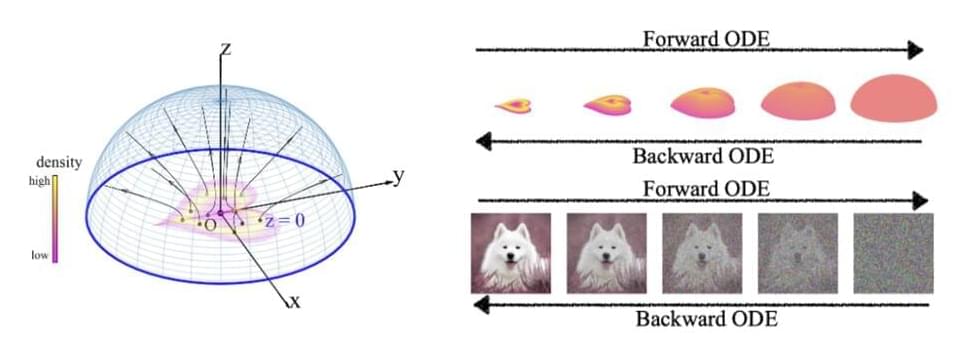

They suggest backward ODEsamplers (normalizing flow) accelerate the sampling process. However, these approaches have yet to outperform their SDE equivalents. We introduce a novel “Poisson flow” generative model (PFGM) that takes advantage of a surprising physics fact that extends to N dimensions. They interpret N-dimensional data items x (say, pictures) as positive electric charges in the z = 0 plane of an N+1-dimensional environment filled with a viscous liquid like honey. As shown in the figure below, motion in a viscous fluid converts any planar charge distribution into a uniform angular distribution.

A positive charge with z 0 will be repelled by the other charges and will proceed in the opposite direction, ultimately reaching an imaginary globe of radius r. They demonstrate that, in the r limit, if the initial charge distribution is released slightly above z = 0, this rule of motion will provide a uniform distribution for their hemisphere crossings. They reverse the forward process by generating a uniform distribution of negative charges on the hemisphere, then tracking their path back to the z = 0 planes, where they will be dispersed as the data distribution.

A team of researchers from HSE MIEM joined colleagues from the Institute of Non-Classical Chemistry in Leipzig to develop a theoretical model of a polymeric ionic liquid on a charged conductive electrode. They used approaches from polymer physics and theoretical electrochemistry to demonstrate the difference in the behavior of electrical differential capacitance of polymeric and ordinary ionic liquids for the first time. The results of the study were published in Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics.

Polymerized ionic liquids (PIL) are a relatively new class of materials with increasing applications in various fields, from the development of new electrolytes to the creation of solar cells. Unlike ordinary room temperature ionic liquids (liquid organic salts in which cations and anions move freely), in PILs, cations are usually linked in long polymeric chains, while anions move freely. In recent years, PILs have been used (along with ordinary ionic liquids) as a filling in the production of supercapacitors.

Supercapacitors are devices that store energy in an electric double layer on the surface of an electrode (as in electrodes of platinum, gold and carbon, for example). Compared, for example, to an accumulator, supercapacitors accumulate more energy and do so faster. The amount of energy a supercapacitor is able to accumulate is known as its ‘capacitance’.

The researchers are one step closer to making the technology viable.

Physicists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) have taken a critical step forward toward achieving nuclear fusion.

The scientists traced back the collapse to the 3D disordering of strong magnetic fields.

Aleksandarnakovski/iStock.

Magnetic fields are used in fusion facilities as substitutes for the powerful gravity that holds fusion reactions in place in celestial bodies. However, in laboratory experiments these fields are disordered by plasma instability resulting in a superhot plasma rapidly escaping confinement. The ensuing heat can damage fusion facility walls.

The 100 MW Dalian Flow Battery Energy Storage Peak-shaving Power Station, with the largest power and capacity in the world so far, was connected to the grid in Dalian, China, on September 29, and it will be put into operation in mid-October.

This energy storage project is supported technically by Prof. Li Xianfeng’s group from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. And the system was built and integrated by Rongke Power Co. Ltd.

The Dalian Flow Battery Energy Storage Peak-shaving Power Station was approved by the Chinese National Energy Administration in April 2016. As the first national, large-scale chemical energy storage demonstration project approved, it will eventually produce 200 megawatts (MW)/800 megawatt-hours (MWh) of electricity.

If there is one thing science fiction movies and comics have taught us, it’s that humans have no.

limitations, and we will one day be able to open a portal that transverses into another dimension. What if I tell you that day is closer to us than ever? This is the latest discovery made.

by scientists and is by far the biggest of the century.

Will we finally get to find out if we are the only beings in the cosmos? What technology have.

scientists designed capable of making interstellar teleportation possible? How and where will.

the portals take us?

Join us as we explore how scientists have finally found a way to open a portal to another.

dimension.

Disclaimer Fair Use:

1. The videos have no negative impact on the original works.

2. The videos we make are used for educational purposes.

3. The videos are transformative in nature.

4. We use only the audio component and tiny pieces of video footage, only if it’s necessary.

DISCLAIMER:

Our channel is purely made for entertainment purposes, based on facts, rumors, and fiction.

Copyright Disclaimer under section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statutes that might otherwise be infringing.

Infinity is back. Or rather, it never (ever, ever…) went away. While mathematicians have a good sense of the infinite as a concept, cosmologists and physicists are finding it much more difficult to make sense of the infinite in nature, writes Peter Cameron.

Each of us has to face a moment, often fairly early in our life, when we realize that a loved one, formerly a fixture in our life, was not infinite, but has left us, and that someday we too will have to leave this place.

This experience, probably as much as the experience of looking at the stars and wondering how far they go on, shapes our views of infinity. And we urgently want answers to our questions. This has been so since the time, two and a half millennia ago, when Malunkyaputta put his doubts to the Buddha and demanded answers: among them he wanted to know if the world is finite or infinite, and if it is eternal or not.