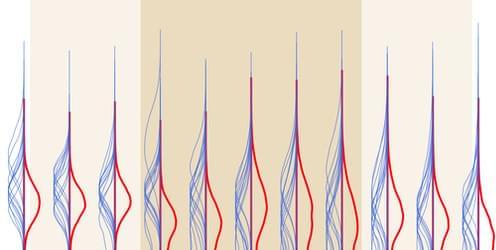

With the upgraded detectors at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and its sister facility Virgo, researchers can now measure significantly finer details of the gravitational-wave signals released from black hole mergers. This progress opens tantalizing prospects for black hole spectroscopy, a technique that involves analyzing the signal-frequency spectra of gravitational waves and that could be used to test the limits of the general theory of relativity. In 2019, an analysis of the first detected gravitational-wave signal (GW150914) indicated that it contained multiple tones, or “overtones” (see Synopsis: Hunting for Hair on Coalescing Black Holes), a finding that could lead to novel spectroscopy approaches. Now a new analysis of GW150914 by Roberto Cotesta of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and colleagues challenges that previous claim. Cotesta and his colleagues find that the suspected overtones could be caused by noise [1].

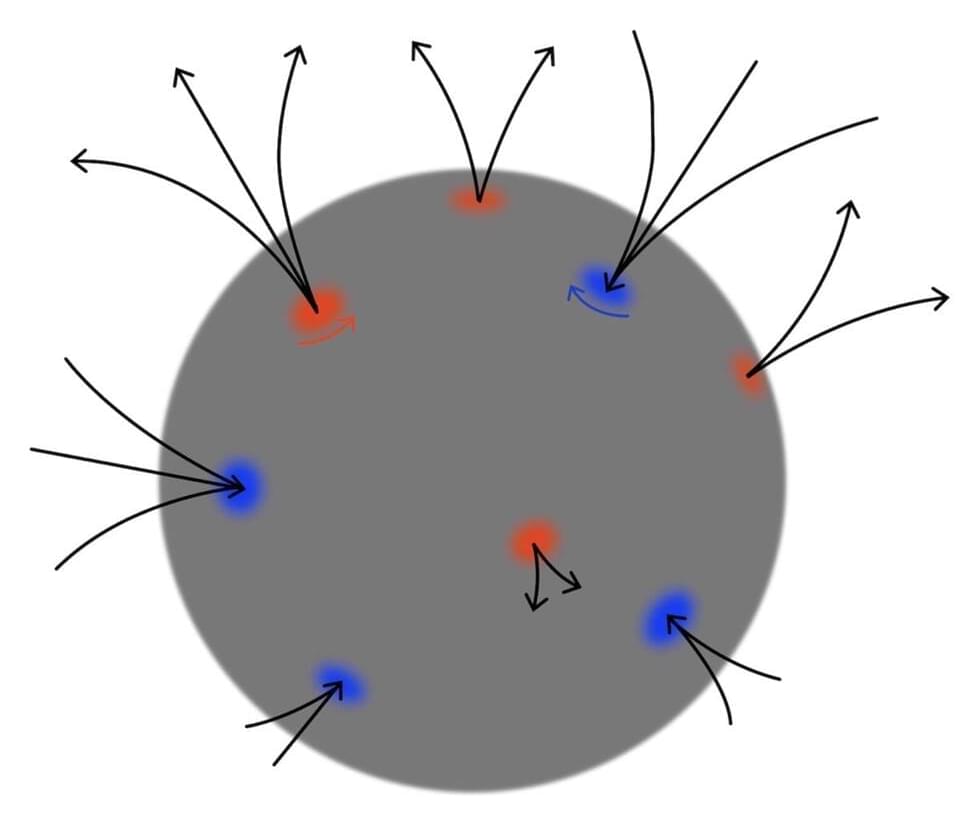

The overtones presented in the 2019 study were extracted from the “ringdown” phase of the merger, when the remnant black hole shakes like a struck bell. Cotesta and his colleagues wanted to test whether that 2019 conclusion was robust to the input assumptions used for the extraction. These assumptions include the time at which the gravitational-wave signal peaks and the noise that contributes to the measured signal. The team finds that the procedure is not robust and that some noise patterns—such as fluctuations occurring right around the signal peak—produce artifacts in the data that resemble overtones.

Theoretical physicist Swetha Bhagwat at the University of Birmingham, UK, who wasn’t involved in either study, says that while neither analysis has obvious faults, the fact that slight differences in the parameters used by the two teams lead to opposing conclusions highlights the need for further scrutiny. The detection of overtones has exciting implications for black hole spectroscopy, so it’s very important that the community debates this issue, she says.