After crunching a mountain of astronomy data, Clarissa Pavao, an undergraduate at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University’s Prescott, Arizona campus, submitted her preliminary analysis. Her mentor’s response was swift and in all-caps: “THERE’S AN ORBIT!” he wrote.

That was when Pavao, a senior space physics major, realized she was about to become a part of something big—a paper in the journal Nature that describes a rare binary star system with uncommon features.

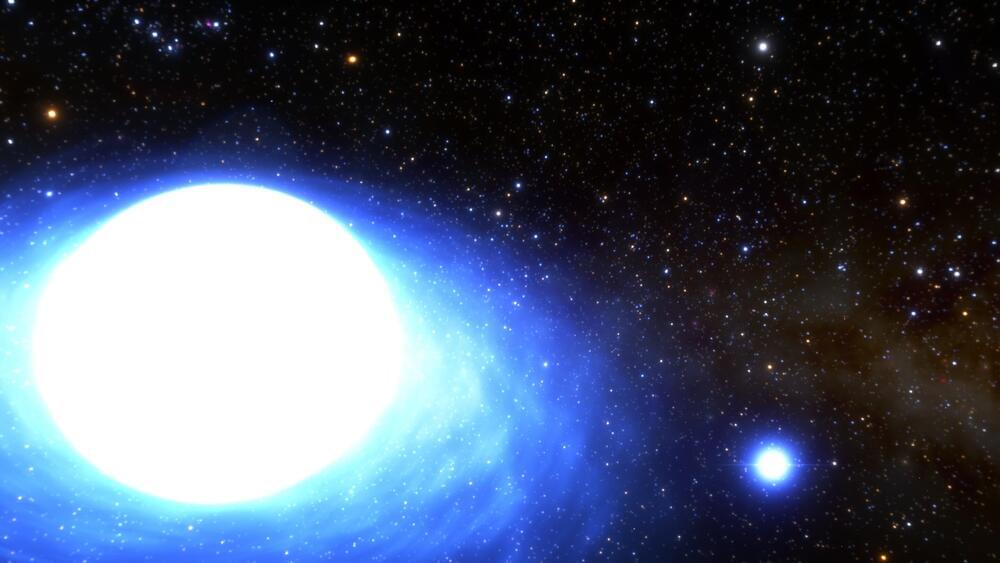

The paper, published on Feb. 1, 2023, and co-authored with Dr. Noel D. Richardson, assistant professor of Physics and Astronomy at Embry-Riddle, describes a twin-star system that is luminous with X-rays and high in mass. Featuring a weirdly circular orbit—an oddity among binaries—the twin system seems to have formed when an exploding star or supernova fizzled out without the usual bang, similar to a dud firecracker.