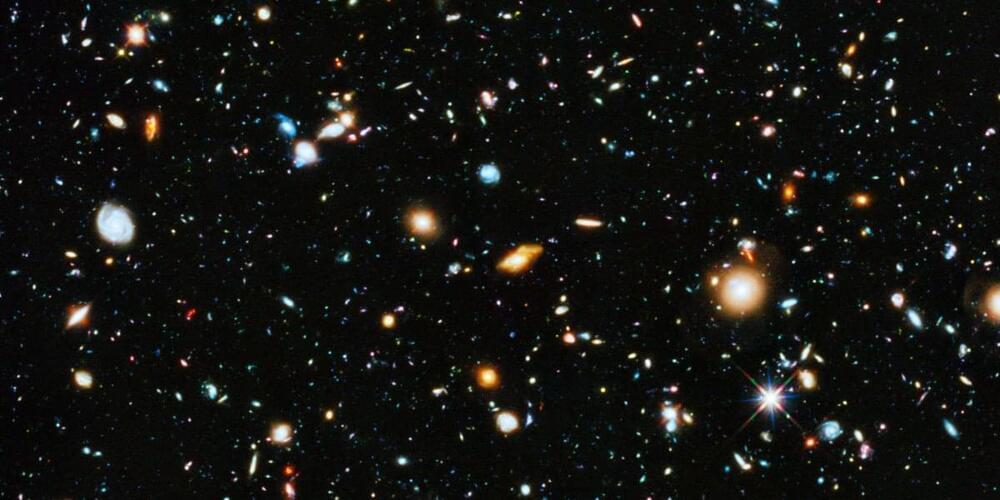

Numerous open questions in gravity theory become apparent from observations in cosmology, such as the cosmic microwave background radiation [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], the large scale structure [7, 8], gravitational waves [9, 10] and supernovae [11]. In order to describe these observations, one needs to study the evolution of both the universe as a whole, modeled by a homogeneous and isotropic background geometry and matter distribution, as well as perturbations of this background. A thorough understanding of such cosmological perturbations and their dynamics imposed by the gravitational interaction is therefore an important necessity for describing and explaining the modern observations in cosmology.

Cosmological perturbations in gravity have been studied for a long time, starting with the case of (pseudo-)Riemannian spacetime geometry, which is employed by the standard formulation of general relativity and the most well-known class of its extensions, in which the gravitational interaction is attributed to the curvature of the metric-compatible, torsion-free Levi-Civita connection [,13,14,15]. This task is significantly simplified by the fact by understanding how perturbations transform under gauge transformations, i.e., infinitesimal diffeomorphisms which retain the nature of the spacetime geometry as a small perturbation of a cosmologically symmetric background. From these gauge transformations, one can derive a set of gauge-invariant perturbation variables, which describe the physical information contained in the metric perturbations as well as the perturbations of the matter variables, so that they become independent of the arbitrary gauge choice. The resulting gauge-invariant perturbation theory is one of the cornerstones of modern cosmology [16,17,18,19].

Despite its overwhelming success in describing observations from laboratory scales up to galactic scales, general relativity is challenged by the aforementioned open questions, as well as the open question how it can be reconciled with quantum theory. This situation motivates the study of modified gravity theories [20]. While numerous theories depart from the standard formulation of general relativity in terms of the curvature of the Levi-Civita connection of a Riemannian spacetime, also other formulations in terms of the torsion or nonmetricity of a flat connection exist and can be used as potential starting points for the construction of modified gravity theories [21, 22]. Focusing on general relativity alone, one finds that these formulations are equivalent in the sense that they lead to field equations which possess the same solutions for the metric irrespective of the geometric properties of the connection under consideration…