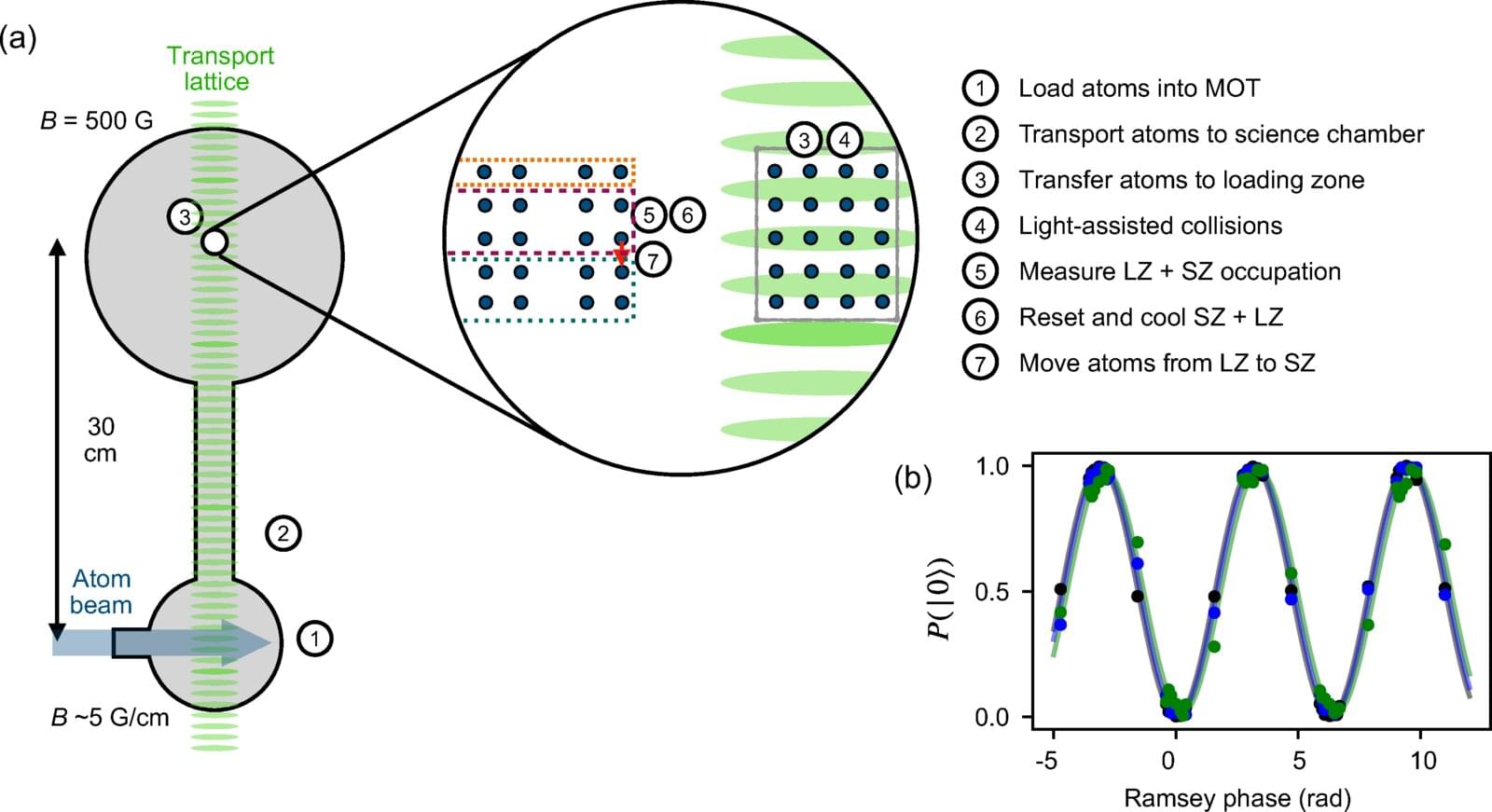

Like their conventional counterparts, quantum computers can also break down. They can sometimes lose the atoms they manipulate to function, which can stop calculations dead in their tracks. But scientists at the US-based firm Atom Computing have demonstrated a solution that allows a quantum computer to repair itself while it’s still running.

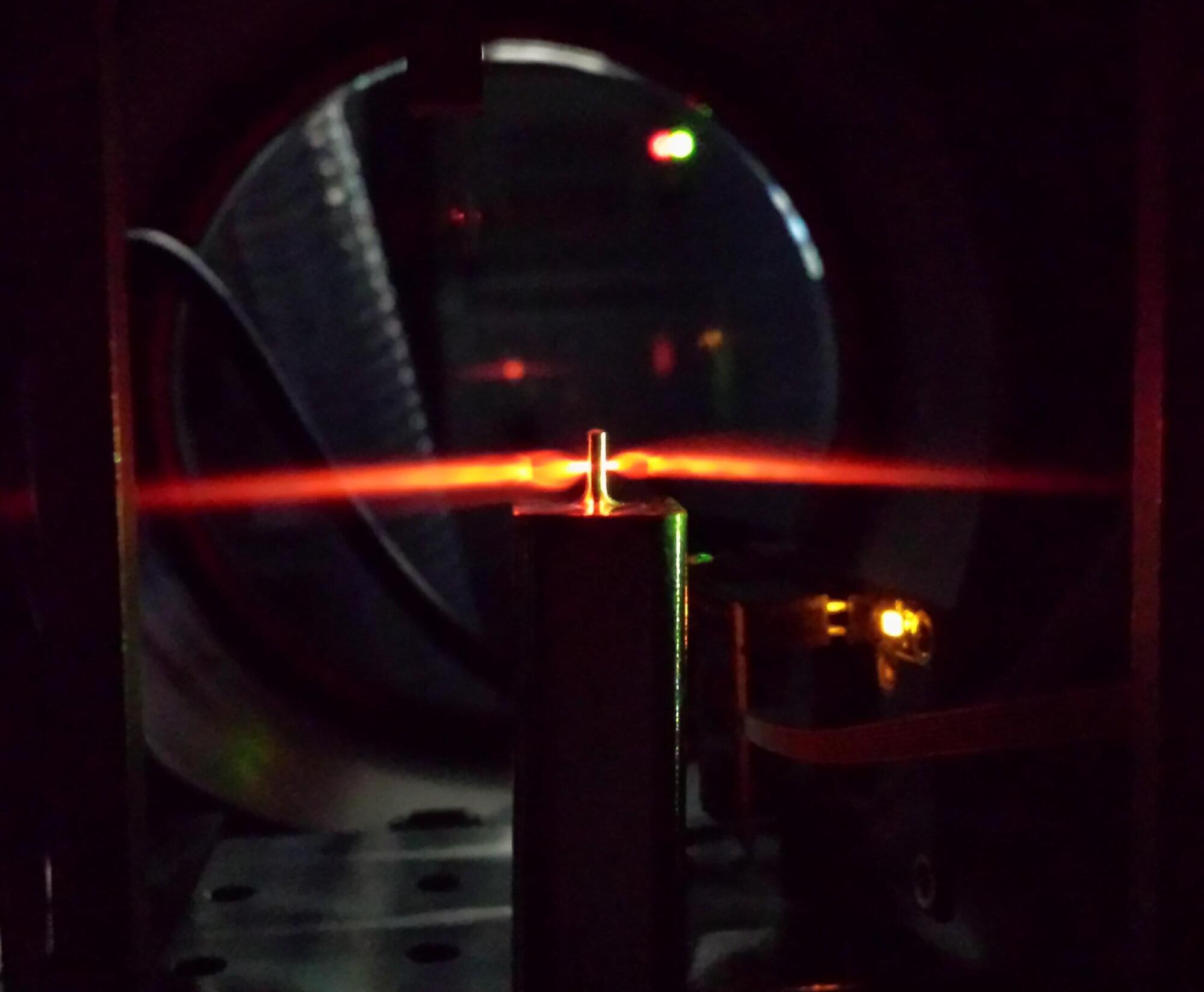

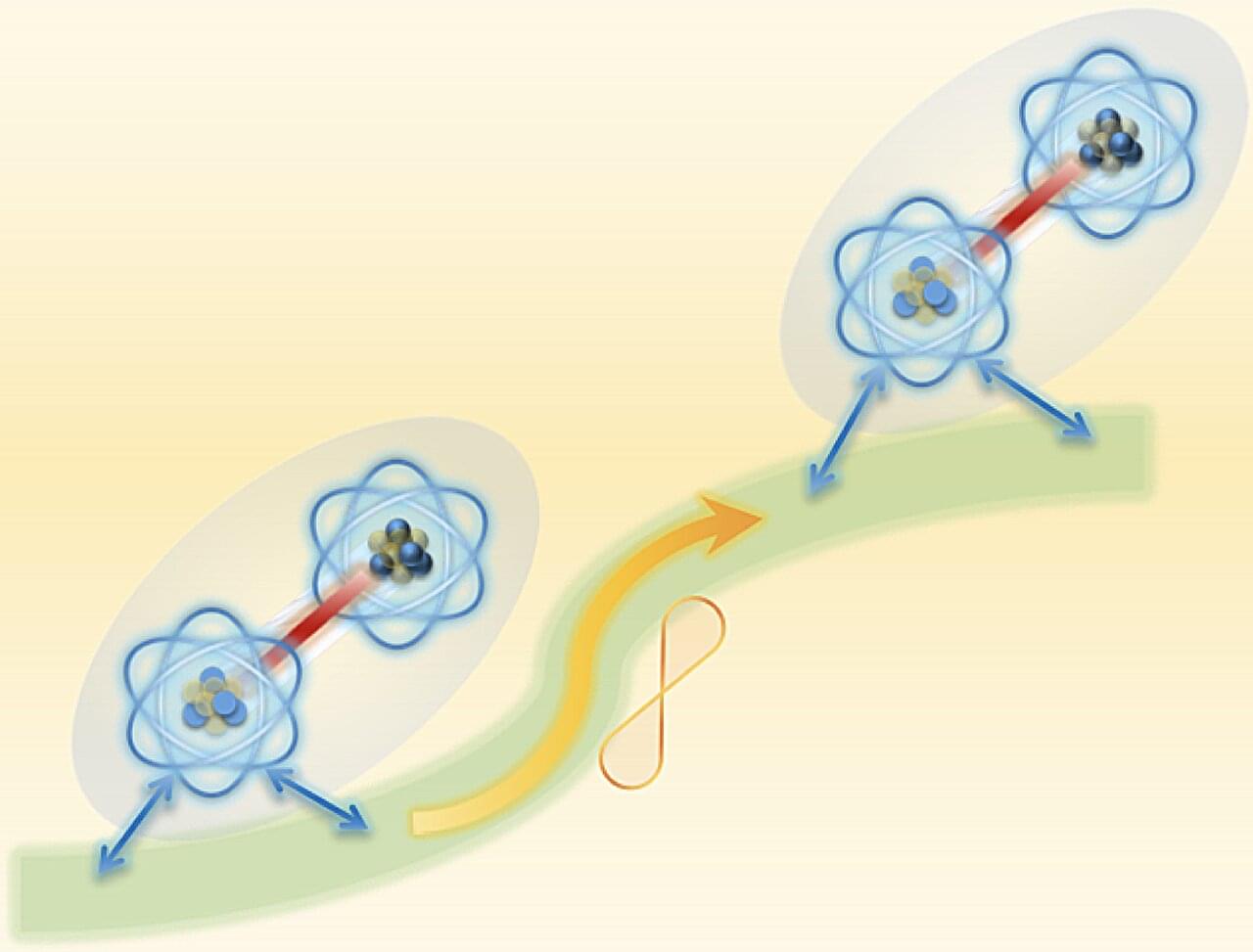

The team zeroed in on quantum computers that use neutral atoms (atoms with equal numbers of protons and electrons). These individual atoms are the qubits, or the basic building blocks of a quantum computer’s memory. They are held in place by laser beams called optical tweezers, but the setup is not foolproof.

Occasionally, an atom slips out of its trap and disappears. When this happens mid-calculation, the whole process can grind to a halt because the computer can’t function with a missing part.