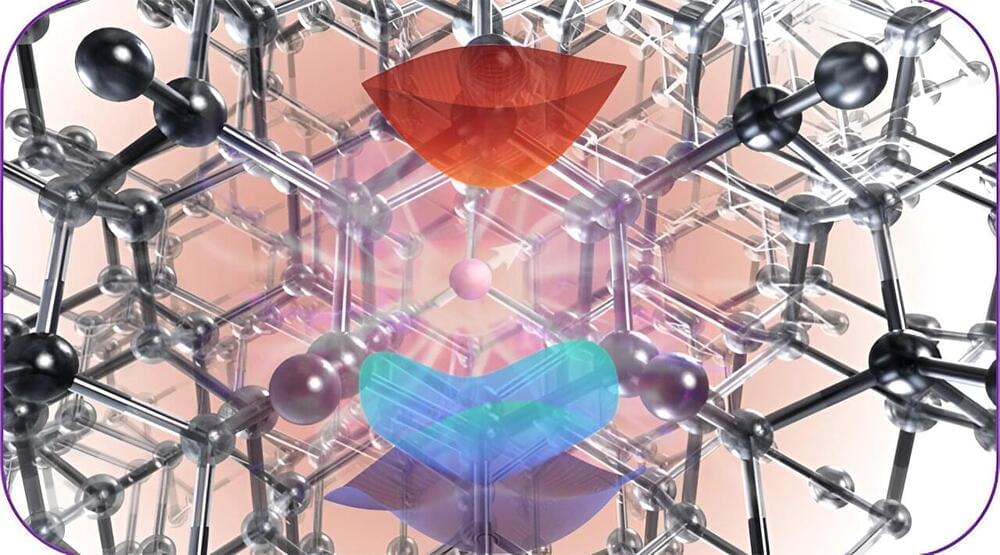

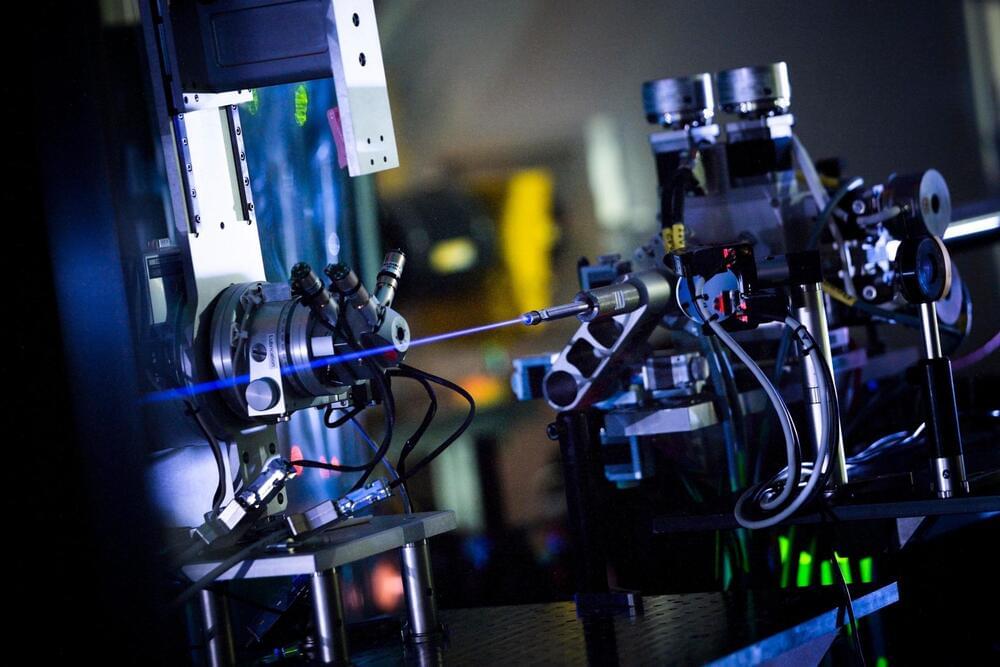

Researchers at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME), Argonne National Laboratory, and the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia have developed a new computational tool to describe how the atoms within quantum materials behave when they absorb and emit light.

The tool will be released as part of the open-source software package WEST, developed within the Midwest Integrated Center for Computational Materials (MICCoM) by a team led by Prof. Marco Govoni, and it helps scientists better understand and engineer new materials for quantum technologies.

“What we’ve done is broaden the ability of scientists to study these materials for quantum technologies,” said Giulia Galli, Liew Family Professor of Molecular Engineering and senior author of the paper, published in Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. “We can now study systems and properties that were really not accessible, on a large scale, in the past.”