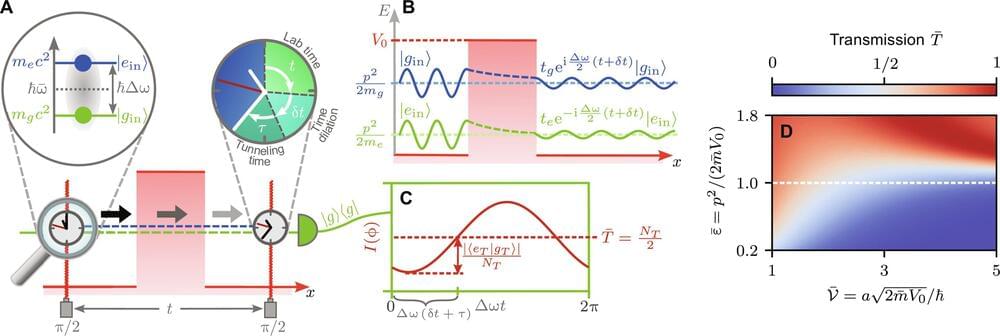

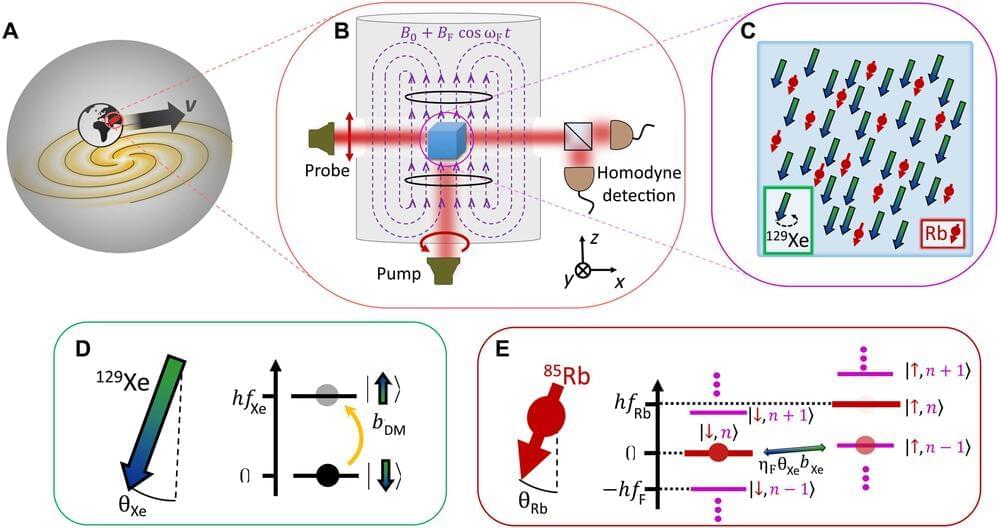

In an amazing phenomenon of quantum physics known as tunneling, particles appear to move faster than the speed of light. However, physicists from Darmstadt believe that the time it takes for particles to tunnel has been measured incorrectly until now. They propose a new method to stop the speed of quantum particles.

In classical physics, there are hard rules that cannot be circumvented. For example, if a rolling ball does not have enough energy, it will not get over a hill, but will turn around before reaching the top and reverse its direction. In quantum physics, this principle is not quite so strict: a particle may pass a barrier, even if it does not have enough energy to go over it. It acts as if it is slipping through a tunnel, which is why the phenomenon is also known as quantum tunneling. What sounds magical has tangible technical applications, for example in flash memory drives.

In the past, experiments in which particles tunneled faster than light drew some attention. After all, Einstein’s theory of relativity prohibits faster-than-light velocities. The question is therefore whether the time required for tunneling was “stopped” correctly in these experiments. Physicists Patrik Schach and Enno Giese from TU Darmstadt follow a new approach to define “time” for a tunneling particle. They have now proposed a new method of measuring this time. In their experiment, they measure it in a way that they believe is better suited to the quantum nature of tunneling.