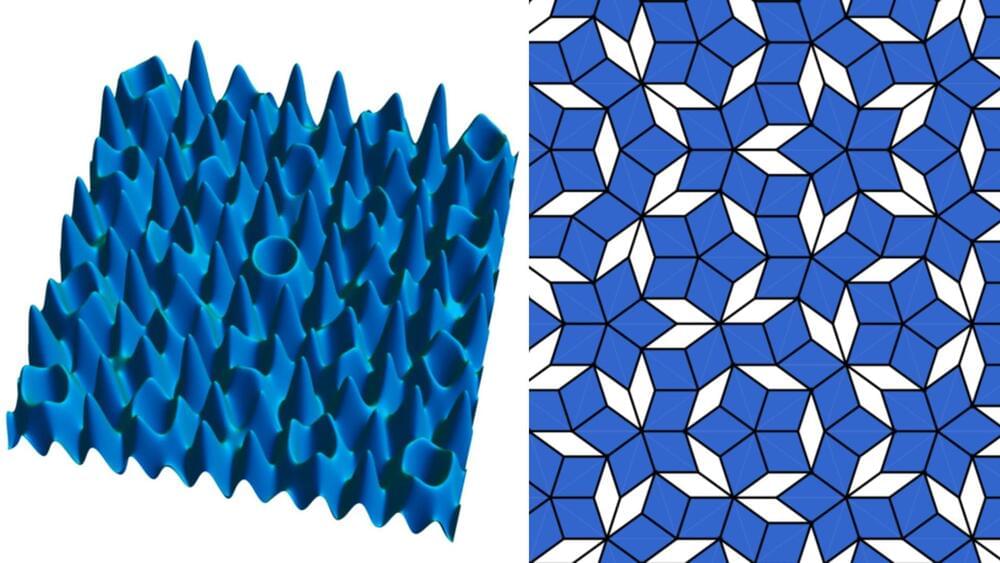

A research team discovered a method to transform materials with three-dimensional atomic structures into nearly two-dimensional structures – a promising advancement in controlling their properties for chemical, quantum, and semiconducting applications.

The field of materials chemistry seeks to understand, at an atomic level, not only the substances that comprise the world but also how to intentionally design and manufacture them. A pervasive challenge in this field is the ability to precisely control chemical reaction conditions to alter the crystal structure of materials—how their atoms are arranged in space with respect to each other. Controlling this structure is critical to attaining specific atomic arrangements that yield unique behaviors. This process results in novel materials with desirable characteristics for practical applications.

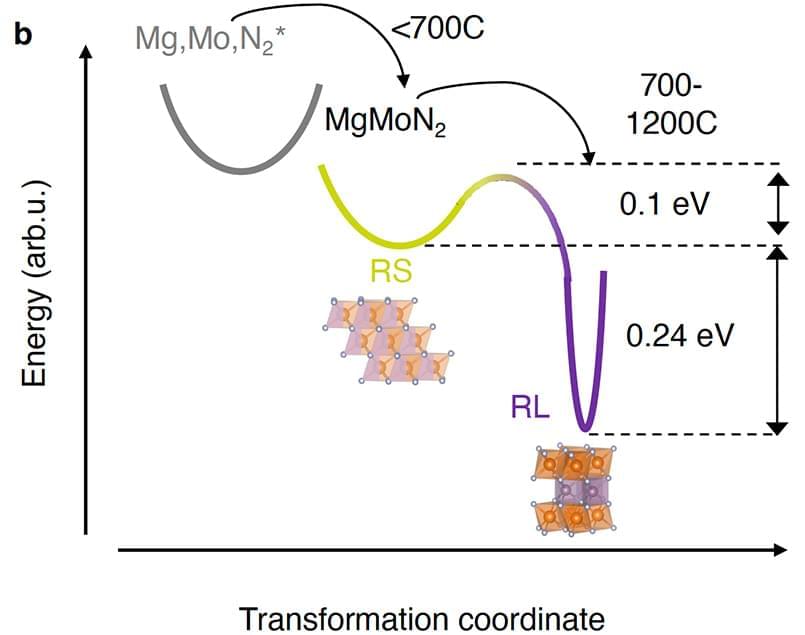

A team of researchers led by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), with contributions from the Colorado School of Mines (Mines), National Institute of Standards and Technology, and Argonne National Laboratory, discovered a method to convert materials from their higher-energy (or metastable) state to their lower-energy, stable state while instilling an ordered and nearly two-dimensional arrangement of atoms—a feat that has the potential to unleash promising material properties.