Three theoretical studies have uncovered novel types of topological order inherent in open quantum systems, enriching our understanding of quantum phases of matter.

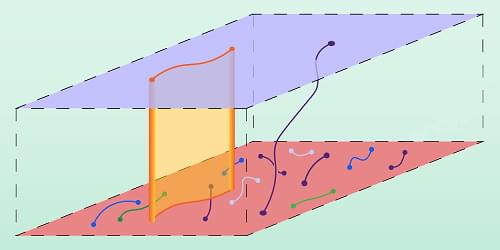

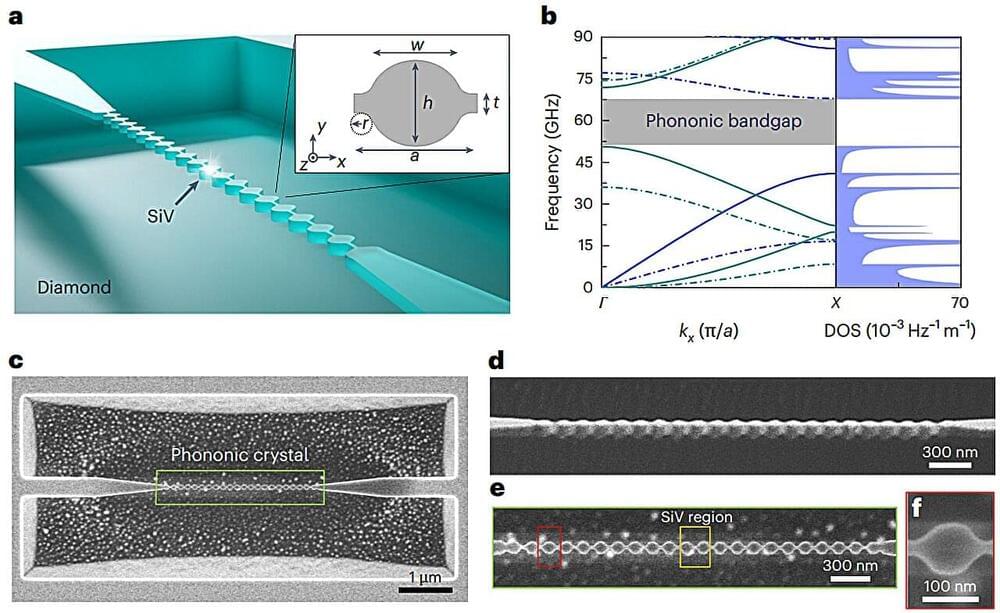

Nature showcases an extraordinary diversity of phases of matter, including many that can be understood only through the principles of quantum mechanics. Such quantum phases can exhibit topological order, characterized by long-range quantum correlations and exotic quasiparticle excitations. Despite extensive theoretical and experimental exploration over the past few decades, our knowledge of topological order has been largely restricted to closed quantum systems. However, real-world quantum systems are inevitably influenced by dissipation and decoherence, underscoring the need for a deeper understanding of open quantum systems—those that exchange energy, particles, or information with their surroundings. Now three research teams have identified new forms of topological order intrinsic to open quantum systems, expanding the spectrum of possible quantum phases and paving the way for advances in quantum information science [1– 3].

Conventionally, different phases of matter are classified based on symmetry. For example, ferromagnets break rotational symmetry since their magnetic moments align in a specific direction, even though the underlying physical laws remain invariant under spatial rotation. While this concept of spontaneous symmetry breaking has proven valuable, the past few decades have seen a new paradigm: topological phases of matter. Representative examples of these phases, such as fractional quantum Hall fluids and quantum spin liquids, display topological order [4]. This property does not arise from spontaneous symmetry breaking but from an intricate pattern of entanglement—nonlocal correlations central to quantum physics.