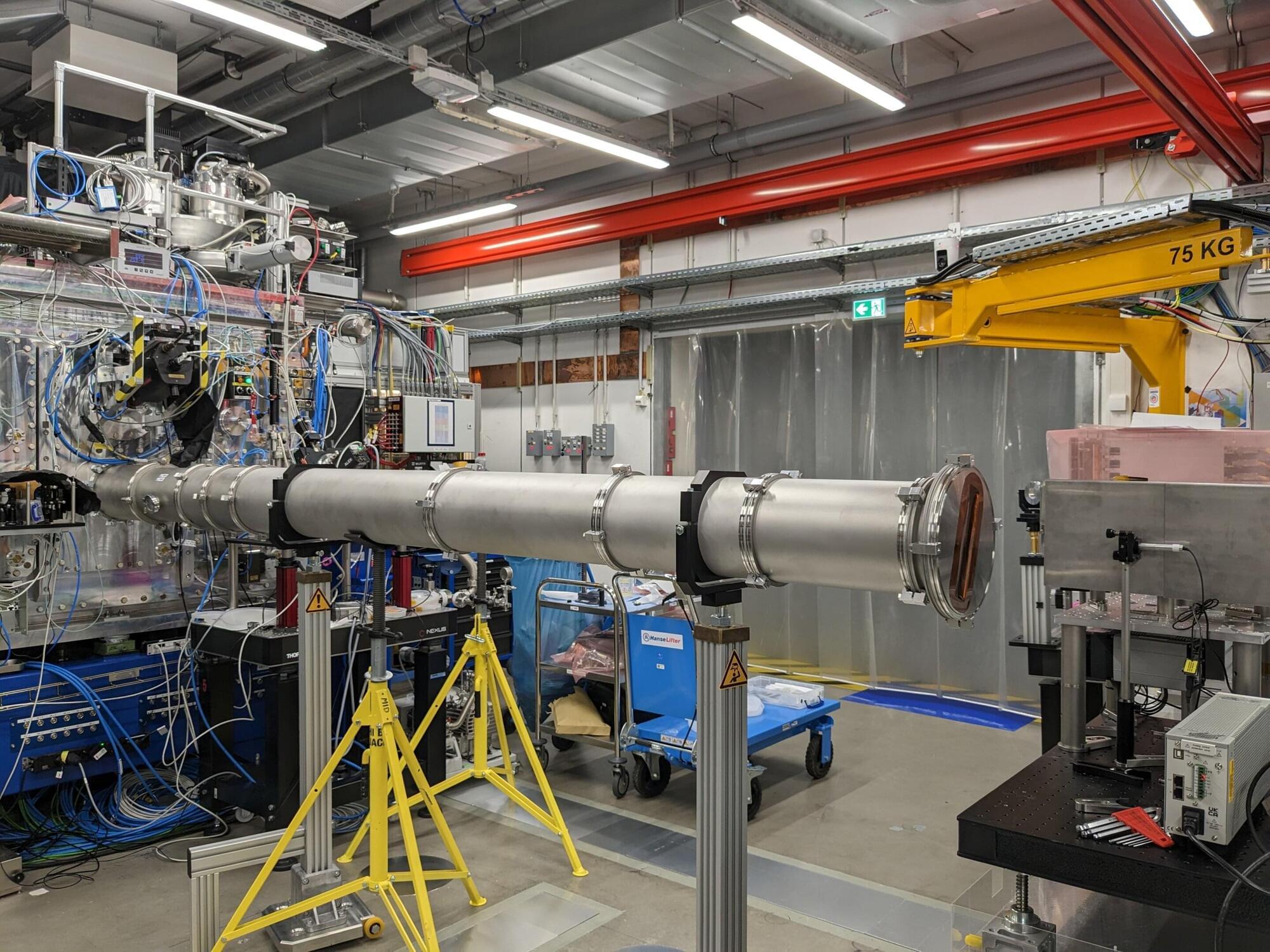

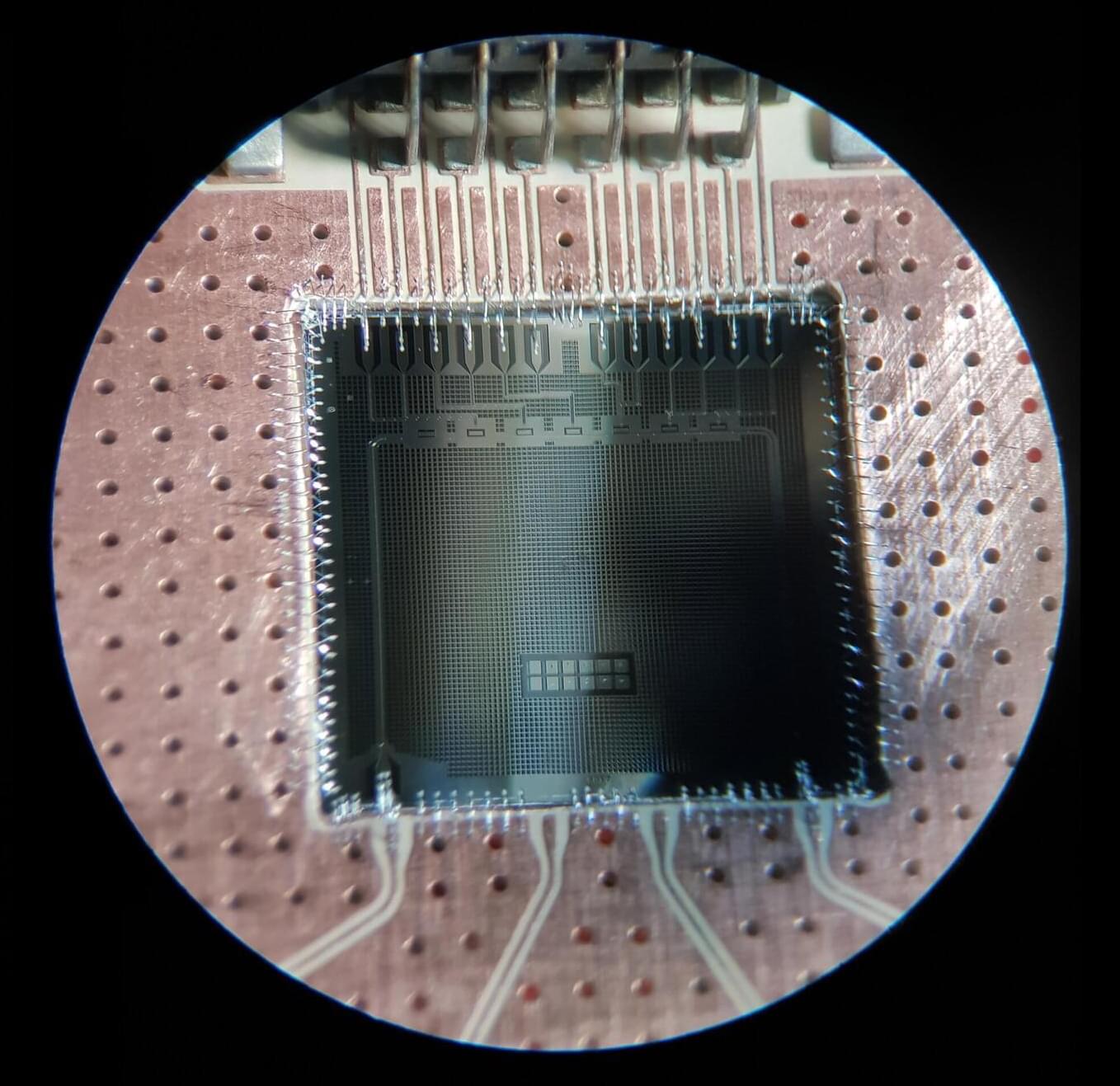

Researchers have announced results from a new search at the European X-ray Free Electron Laser (European XFEL) Facility at Hamburg for a hypothetical particle that may make up the dark matter of the universe. The experiment is described in a study published in Physical Review Letters.

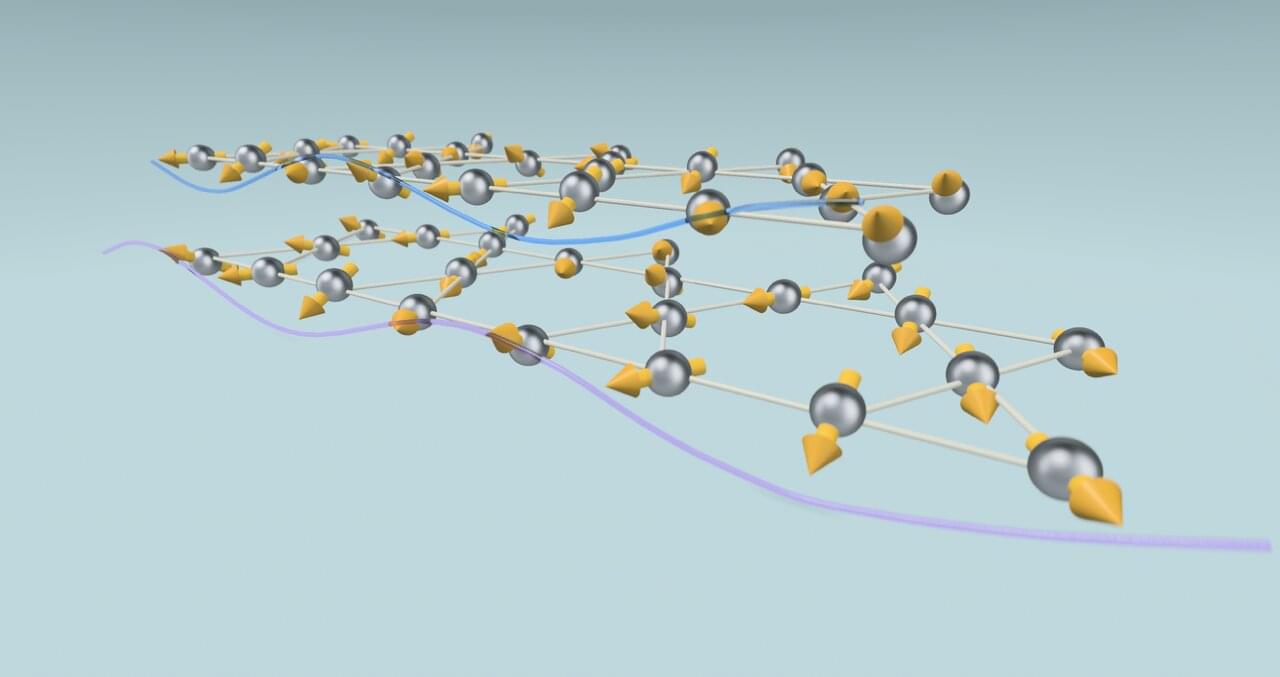

This experiment looks for axions, a particle which was proposed to solve a major problem in particle physics: why neutrons, although composed of smaller charged particles called quarks, do not possess an electric dipole moment. To explain this, it was suggested that axions, tiny and incredibly light particles, can “cancel out” this imbalance. If observed, this process would provide direct evidence for new physics beyond the Standard Model.

Additionally, axions turn out to be a natural candidate for dark matter, the mysterious substance that constitutes most of the structure of the universe.