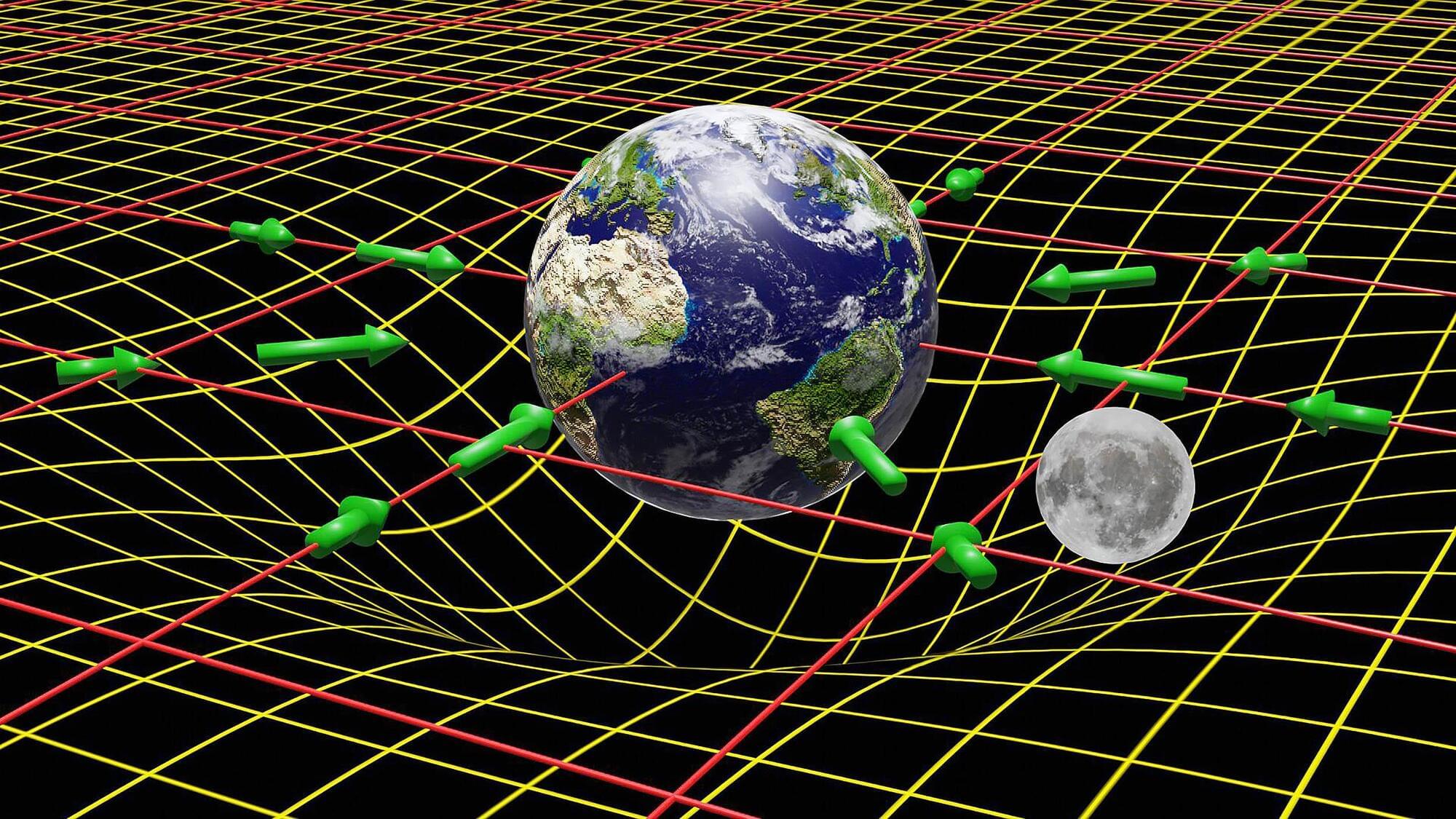

Quantum technologies, which leverage quantum mechanical effects to process information, could outperform their classical counterparts in some complex and advanced tasks. The development and real-world deployment of these technologies partly relies on the ability to transfer information between different types of quantum systems effectively.

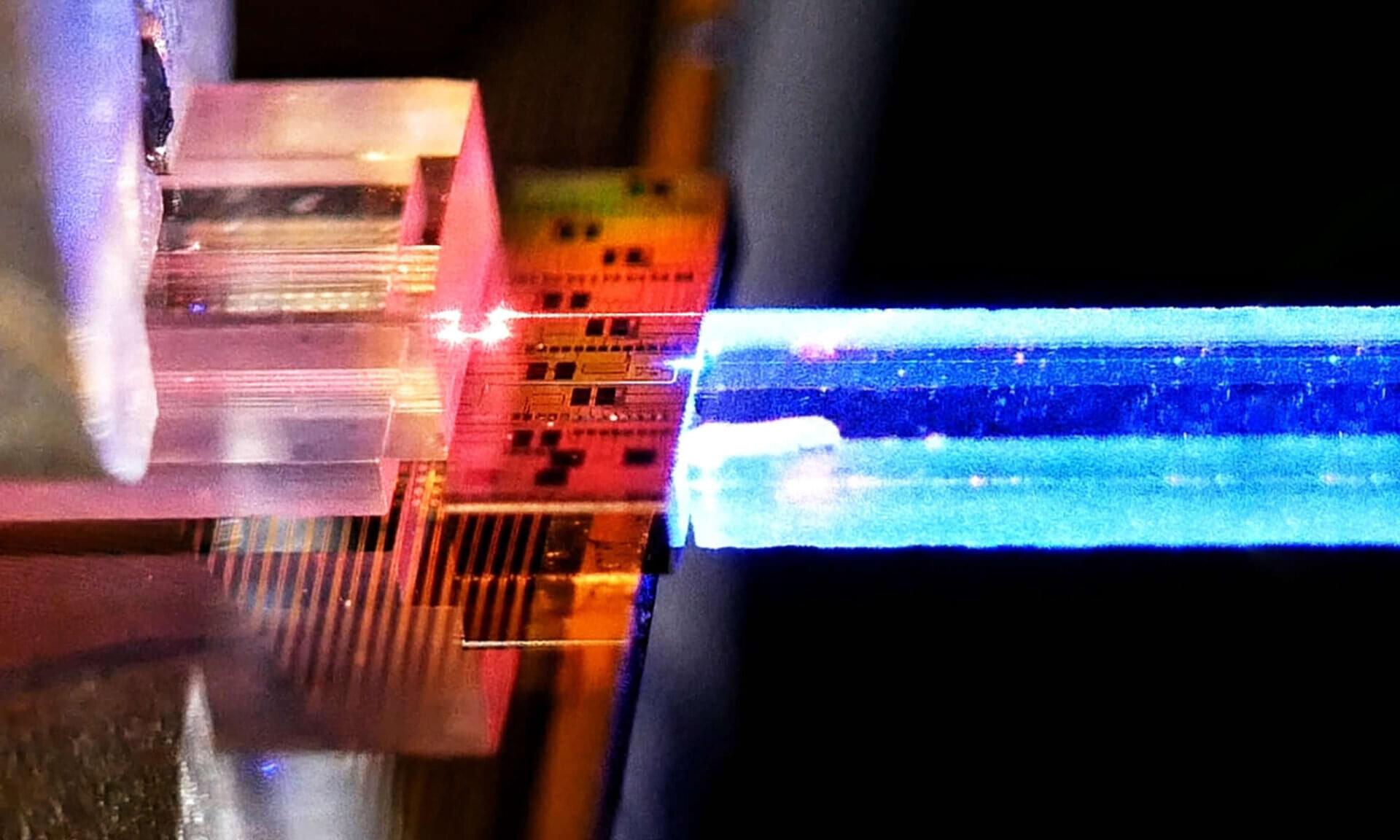

A long-standing challenge in the field of quantum technology is converting quantum signals carried by microwave photons (i.e., particles of electromagnetic radiation in the microwave frequency range) into optical photons (i.e., visible or near visible light particles). Devices designed to perform this conversion are known as microwave-to-optical transducers.

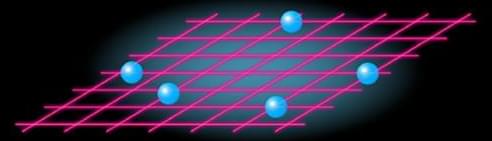

Researchers at the California Institute of Technology recently developed a new microwave-to-optical transducer based on rare-earth ion-doped crystals. Their on-chip transducer, outlined in a paper published in Nature Physics, was implemented using ytterbium-171 ions doped in a YVO4 crystal.