The existing treatment options include biological and targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, which some patients find hard to tolerate, and around 50 percent of patients discontinue their therapies within two years. SetPoint’s goal is to provide an alternative that can effectively manage autoimmune conditions without suppressing the immune system.

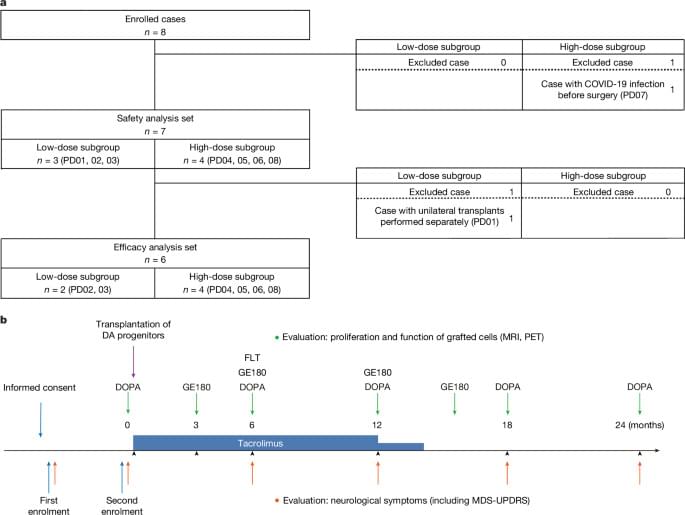

Its FDA approval follows a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study that followed 242 patients. It showed that the therapy was well-tolerated with a low level of serious adverse events related to it (1.7 percent). It also provides a long-term solution for patients living with this chronic disease.

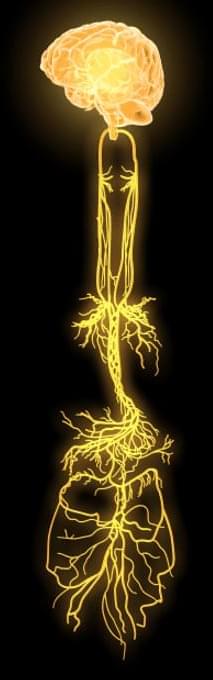

“The approval of the SetPoint System highlights the potential of neuroimmune modulation as a novel approach for autoimmune disease, by harnessing the body’s neural pathways to combat inflammation,” said the study’s principal investigator, Dr Mark Richardson, Director of Functional Neurosurgery at Massachusetts General Hospital and Professor of Neurosciences at Harvard Medical School, in a statement. “After implantation during a minimally invasive outpatient procedure, the SetPoint device is programmed to automatically administer therapy on a predetermined schedule for up to 10 years, simplifying care for people living with RA.”