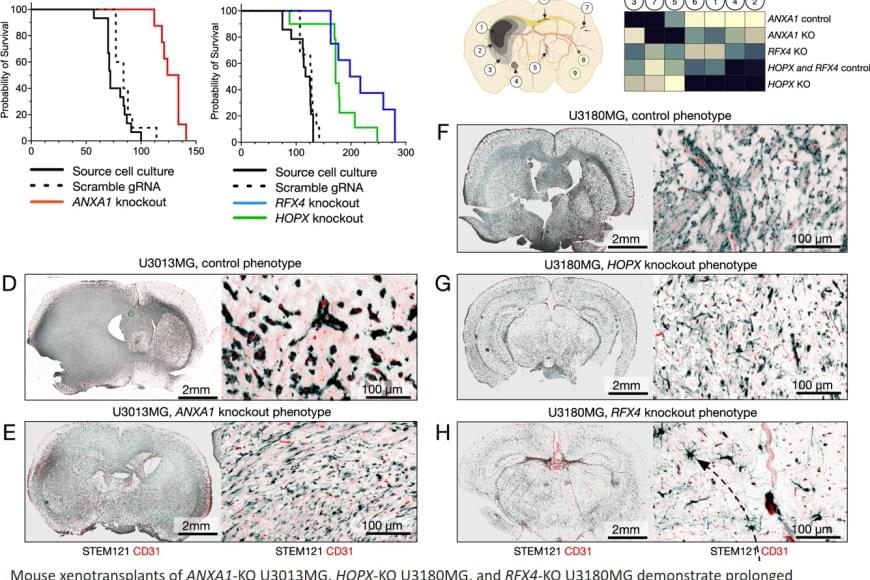

The researchers identified three key factors involved in controlling the invasion routes. The gene ANXA1 was linked to invasion along blood vessels while HOPX and RFX4 was associated with diffuse infiltration in the brain. To evaluate the role of the genes, the researchers tested to knock them out in preclinical models, which resulted in a shift in the tumor’s invasion pattern. In several cases, the survival of the experimental animals was also prolonged.

The researchers also discovered proteins encoded by the identified genes in tissue samples from patients. In addition, they found that the presence of the ANXA1 and RFX4 correlated with poor survival. This indicates that these proteins could have a value as prognostic biomarkers.

An international research team has identified new mechanisms behind how the aggressive brain tumor glioblastoma spreads in the brain. Targeting the identified connection between the tumor invasion routes and the tumor cell states could be a potential new treatment strategy.

Glioblastoma is the most common and most lethal primary brain cancer in adults, known for its capacity to spread locally in the brain rather than forming distant metastases. The locally infiltrating cells are largely out of reach for current therapies and it is therefore crucial to determine how the spread in the brain is controlled.

In the current study, which was recently published in the journal Nature Communications, the researchers found that some tumor cells choose to grow along blood vessels in the brain whereas others spread diffusely in the brain tissue. This choice is controlled by the tumor cell states.