Futuristic advancements in AI and healthcare stole the limelight at the tech extravaganza Consumer Electronics Show (CES) 2024. However, battery technology is the game-changer at the heart of these innovations, enabling greater power efficiency. Importantly, electric vehicles are where this technology is being applied most intensely. Today’s EVs can travel around 700km on a single charge, while researchers are aiming for a 1,000km battery range. Researchers are fervently exploring the use of silicon, known for its high storage capacity, as the anode material in lithium-ion batteries for EVs. However, despite its potential, bringing silicon into practical use remains a puzzle that researchers are still working hard to piece together.

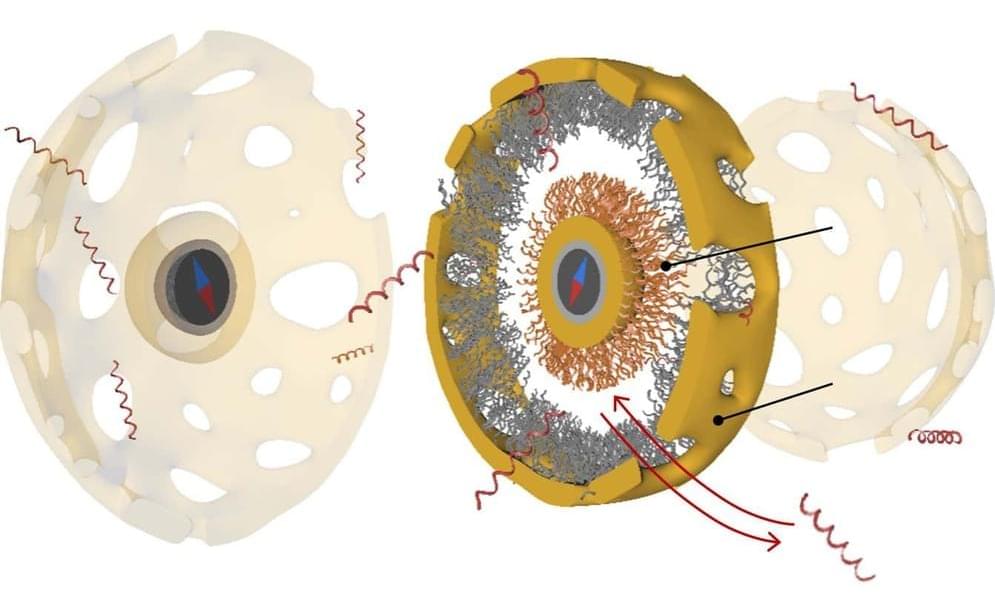

Enter Professor Soojin Park, PhD candidate Minjun Je, and Dr. Hye Bin Son from the Department of Chemistry at Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH). They have cracked the code, developing a pocket-friendly and rock-solid next-generation high-energy-density Li-ion battery system using micro silicon particles and gel polymer electrolytes. This work was published on the online pages of Advanced Science on the 17th of January.

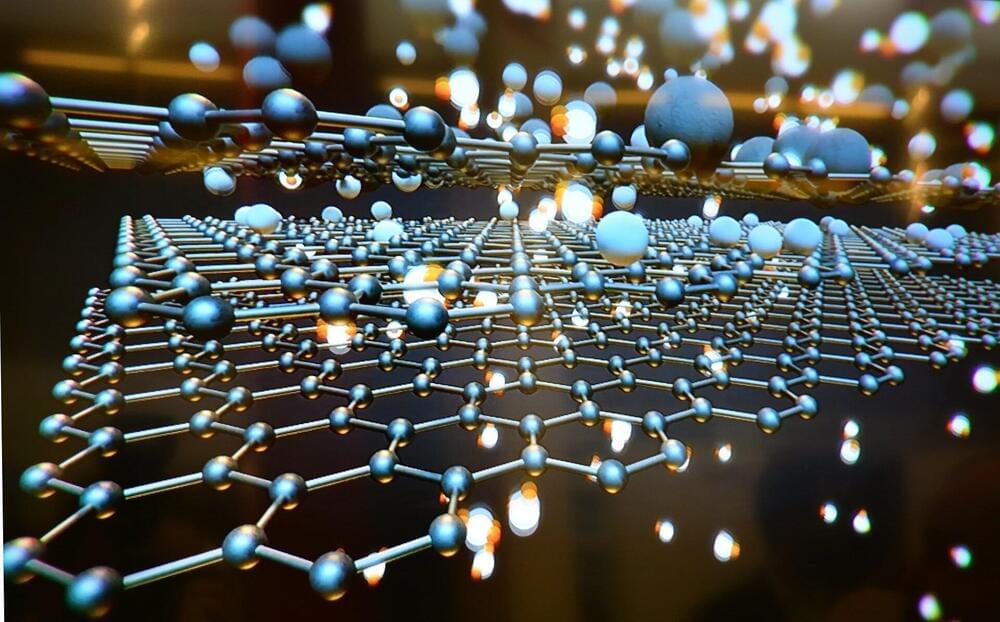

Employing silicon as a battery material presents challenges: It expands by more than three times during charging and then contracts back to its original size while discharging, significantly impacting battery efficiency. Utilizing nano-sized silicon (10-9m) partially addresses the issue, but the sophisticated production process is complex and astronomically expensive, making it a challenging budget proposition. By contrast, micro-sized silicon (10-6m) is superbly practical in terms of cost and energy density. Yet, the expansion issue of the larger silicon particles becomes more pronounced during battery operation, posing limitations for its use as an anode material.