Osteoarthritis (OA) is a prevalent global health concern, posing a significant and increasing public health challenge worldwide. Recently, biomaterials have emerged as a highly promising strategy for OA therapy due to their exceptional physicochemical properties and capacity to regulate pathological processes. However, there is an urgent need for a deeper understanding of the potential therapeutic applications of these biomaterials in the clinical management of diseases, particularly in the treatment of OA. In this comprehensive review, we present an extensive discussion of the current status and future prospects concerning biomaterials for OA… More.

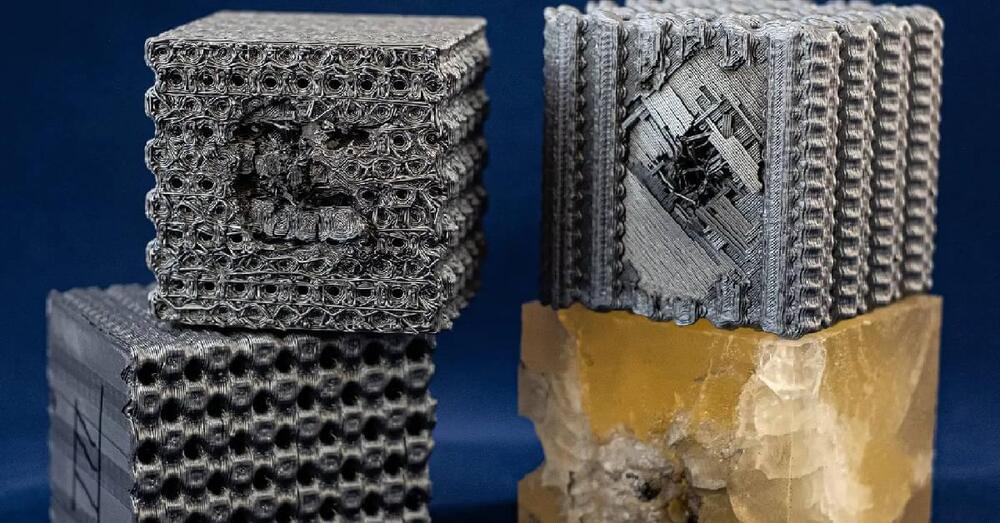

Herein, in this review, we summarize the advanced strategies developed for enhancing OA therapy based on the biomaterials. We conducted a comprehensive literature search using relevant databases such as PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search was focused on peer-reviewed articles and research papers published within the last ten years (from 2013 to 2023). We utilized specific keywords related to biomaterials”, biomaterials” and “osteoarthritis therapy” to retrieve relevant studies. First, we provide an overview of the pathophysiology of OA and the limitations of current treatment options. Second, we explore the various types of biomaterials which have been used for OA therapy, including nanoparticles, nanofibers, and nanocomposites. Third, we highlight the advantages and challenges associated with the use of biomaterials in OA therapy, such as toxicity, biodegradation, and regulatory issues. Finally, advanced biomaterials-based OA therapies with their potential for clinical translation and emerging biomaterials directions for OA therapy are discussed.

Characteristics of Biomaterials

Nanotechnology-boosted biomaterials have attracted considerable attention in recent years as promising candidates for revolutionizing the field of therapeutics.12,13 These materials combine the unique properties of nanotechnology with the versatility and biocompatibility of biomaterials, offering numerous advantages over existing therapeutic approaches. Nanotechnology enables the precise engineering of biomaterials at the nanoscale, allowing for the encapsulation and controlled release of therapeutic agents, such as drugs and growth factors.14–17 This feature facilitates targeted and sustained drug delivery to specific sites within the body, reducing systemic side effects and enhancing treatment efficacy. In the context of OA, this targeted drug delivery can be utilized to deliver anti-inflammatory agents or disease-modifying drugs directly to affected joint tissues, promoting tissue repair and alleviating symptoms. Furthermore, biomaterials can be designed to mimic the native tissue environment, thereby enhancing their biocompatibility and reducing the risk of adverse reactions or immune responses.18 This characteristic is crucial for successful integration and long-term functionality of biomaterials in biomedical applications. Moreover, nanomaterials can facilitate tissue regeneration by stimulating cellular responses and promoting tissue growth.19 In the context of OA, biomaterials can assist in cartilage repair and regeneration, potentially slowing down disease progression and improving joint function.3 In addition, nanotechnology allows for the customization of biomaterials with a wide range of physical, chemical, and biological properties.13 This flexibility enables the development of multifunctional biomaterials that can simultaneously perform multiple tasks, such as drug delivery, imaging, and tissue regeneration. These advantages collectively contribute to their potential as innovative solutions in addressing various biomedical challenges and improving patient outcomes. In this section, we will discuss some of the key properties of biomaterials and their impact on OA treatment.