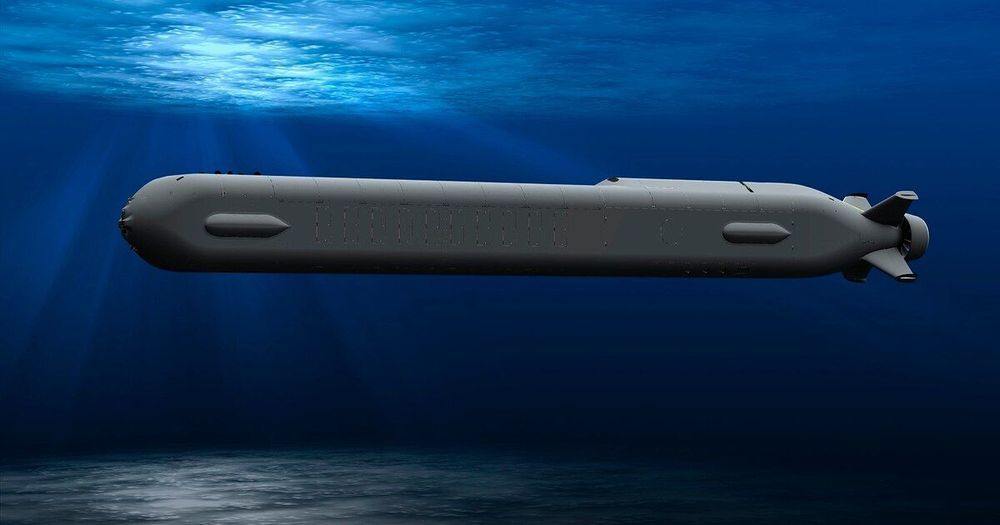

Here’s What You Need To Remember: Chinese so-called “carrier-killer” missiles could, quite possibly, push a carrier back to a point where its fighters no longer have range to strike inland enemy targets from the air. The new drone is being engineered, at least in large measure, as a specific way to address this problem. If the attack distance of an F-18, which might have a combat radius of 500 miles or so, can double — then carrier-based fighters can strike targets as far as 1000 miles away if they are refueled from the air.

The Navy will choose a new carrier-launched drone at the end of this year as part of a plan to massively expand fighter jet attack range and power projection ability of aircraft carriers.

The emerging Navy MQ-25 Stingray program, to enter service in the mid-2020s, will bring a new generation of technology by engineering a first-of-its-kind unmanned re-fueler for the carrier air wing.