Microsoft president: Orwell’s 1984 could happen in 2024.

Tech executives warned that democracy has to win the AI arms race, in a new BBC Panorama.

‘Quasicrystals’ like these are usually only found in meteorites and formed in the universe’s mightiest explosions.

Welcome to the rapidly advancing world of autonomous weapons — the cheap, highly effective systems that are revolutionizing militaries around the world. These new unmanned platforms can make U.S. forces much safer, at far lower cost than aircraft carriers and fighter jets. But beware: They’re being deployed by our potential adversaries faster than the Pentagon can keep up, and they increase the risk of conflict by making it easier and less bloody for the attacker.

Artificial intelligence and drones are transforming the battlefield into something that looks more like a video game than hand-to-hand combat. It could save lives — but also increase the risk of combat.

“The Russian military is more technologically advanced than the U.S. realized and is quickly developing artificial intelligence capabilities to gain battlefield information advantage, an expansive new report commissioned by the Pentagon warned.”

Need more money for AI research.

A new report written for the Pentagon warns of more technologically advanced Russian force that’s focused on winning information advantage over the United States.

The Israeli military is calling Operation Guardian of the Walls the first artificial-intelligence war. the IDF established an advanced AI technological platform that centralized all data on terrorist groups in the Gaza Strip onto one system that enabled the analysis and extraction of the intelligence.

The IDF used artificial intelligence and supercomputing during the last conflict with Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

Oh, joy. You can take the drone out of 2020, but you can’t take the 2020 out of the drone.

A “lethal” weaponized drone “hunted down a human target” without being told to for the first time, according to a UN report seen by the New Scientist.

The March 2020 incident saw a KARGU-2 quadcopter autonomously attack a human during a conflict between Libyan government forces and a breakaway military faction, led by the Libyan National Army’s Khalifa Haftar, the Daily Star reported.

The Turkish-built KARGU-2, a deadly attack drone designed for asymmetric warfare and anti-terrorist operations, targeted one of Haftar’s soldiers while he tried to retreat, according to the paper.

It’s only the country’s second new fighter design since the end of the Cold War.

Russia’s famed Sukhoi Design Bureau is reportedly working on a brand-new, fifth-generation fighter jet: a lightweight fighter capable of flying faster than Mach 2.

The unnamed fighter would likely complement the larger, heavier Su-57 fighter jet (pictured above) and would use at least some of the same components.

According to an industry source via Russian state media’s RIA Novosti, the fifth-gen fighter will have one engine, a reduced radar signature, “super maneuverability,” and thrust vectoring capabilities. The source also said the plane could be offered in manned and unmanned versions.

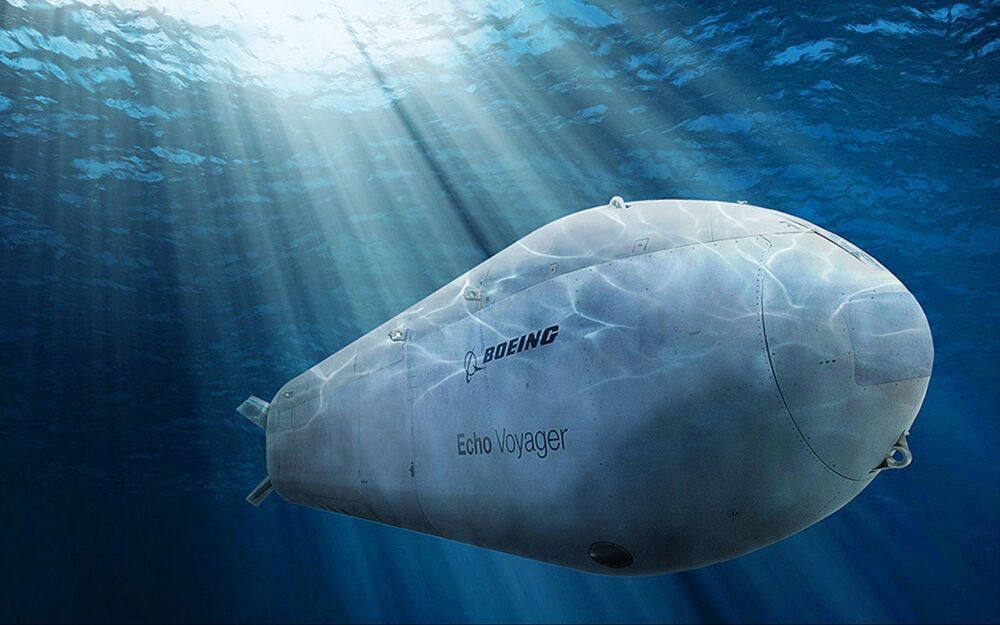

The 50-ton Voyager was developed by Boeing’s PhantomWorks division, which is devoted to advanced new technologies, succeeding a series of smaller Echo Seeker and Echo Ranger UUVs. The 15.5-meter long Echo Voyager has a range of nearly 7500 miles. It has also deployed at sea up to three months in a test, and theoretically could last as long as six months.

Supposedly, Voyager also can dive as deep as 3350 meters—while few military submarines are (officially) certified for dives below 500 meters.

And it isn’t the only robot submarine in the works.

Here’s What You Need to Know: The U.S. Navy has an ambitious vision for future warfare.

At a military parade celebrating its 70th anniversary, the People’s Republic of China unveiled, amongst many other exotic weapons, two HSU-001 submarines—the world’s first large diameter autonomous submarines to enter military service.