The feature image you see above was generated by an AI text-to-image rendering model called Stable Diffusion typically runs in the cloud via a web browser, and is driven by data center servers with big power budgets and a ton of silicon horsepower. However, the image above was generated by Stable Diffusion running on a smartphone, without a connection to that cloud data center and running in airplane mode, with no connectivity whatsoever. And the AI model rendering it was powered by a Qualcomm Snapdragon 8 Gen 2 mobile chip on a device that operates at under 7 watts or so.

It took Stable Diffusion only a few short phrases and 14.47 seconds to render this image.

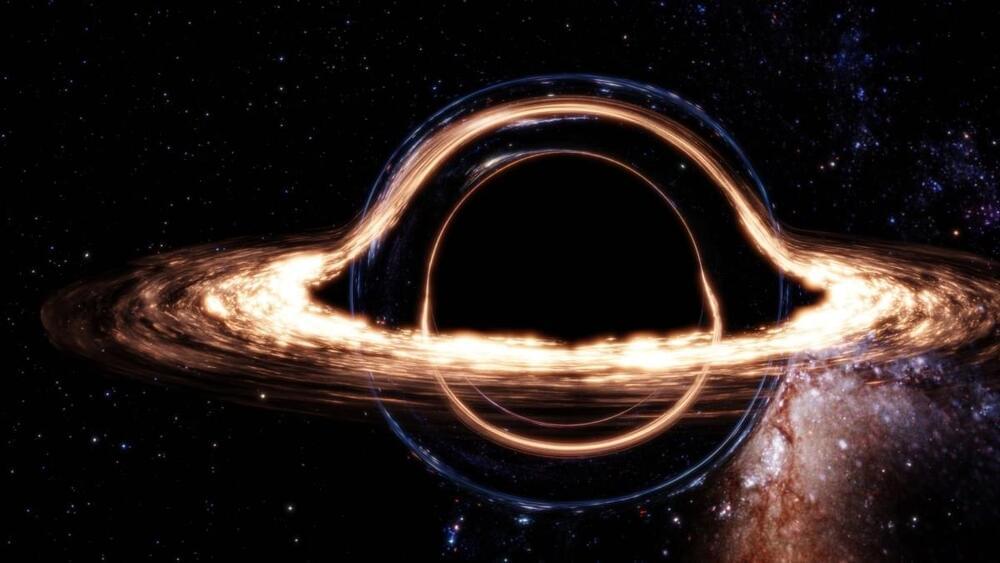

This is an example of a 540p pixel input resolution image being scaled up to 4K resolution, which results in much cleaner lines, sharper textures, and a better overall experience. Though Qualcomm has a non-algorithmic version of this available today, called Snapdragon GSR, someday in the future, mobile enthusiast gamers are going to be treated to even better levels of image quality without sacrificing battery life and with even higher frame rates.

This is just one example of gaming and media enhancement with pre-trained and quantized machine learning models, but you can quickly think of a myriad of applications that could benefit greatly, from recommendation engines to location-aware guidance, to computational photography techniques and more.

We just needed a new math for all this AI heavy lifting on smartphones and other lower power edge devices, and it appears Qualcomm is leading that charge.