Who will invent molecular jousting?

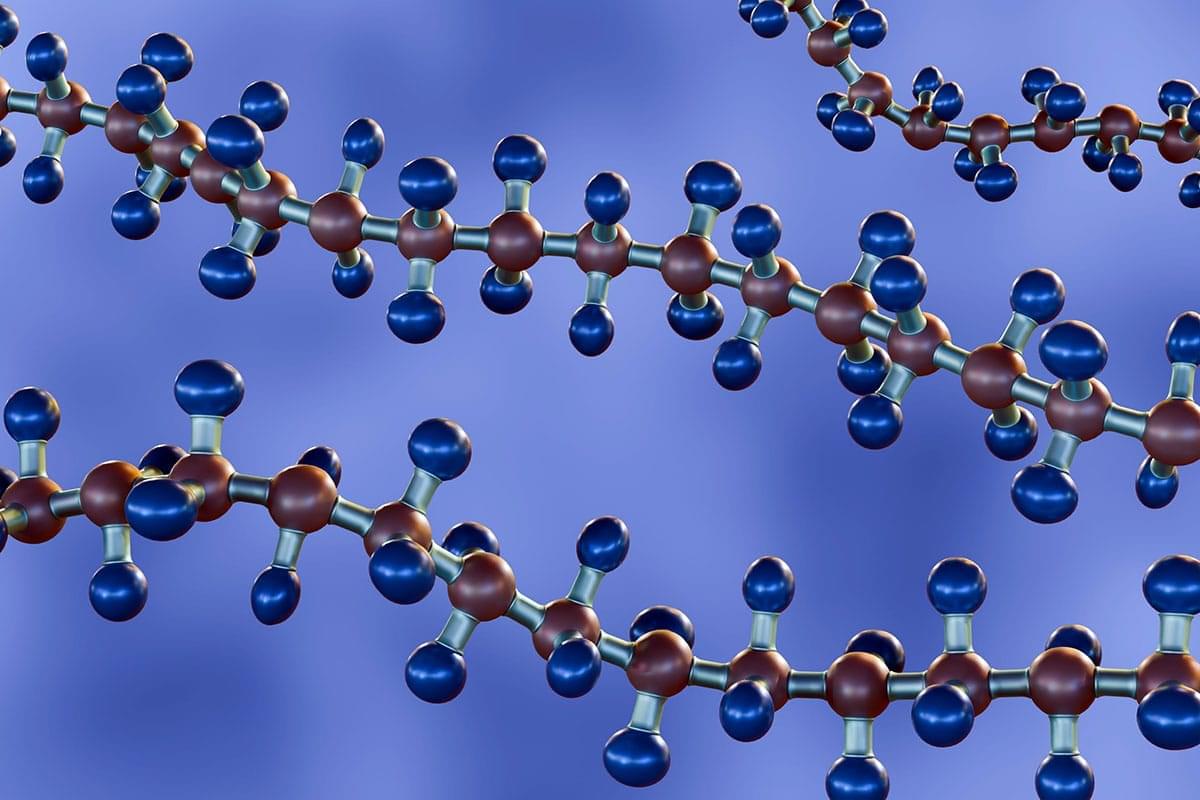

A research team has discovered that by using a new method of “atomic spray painting,” they can tweak the atomic structure of lead-free potassium niobate in order to enhance its ferroelectric properties.

The study, created by a team led by Penn State researchers, explains how molecular beam epitaxy can be employed to deposit atomic layers onto a substrate to create thin films, as a report by SciTechDaily explained.

Using a technique called strain tuning, the researchers adjusted how successive layers are aligned to modify a material’s properties by stretching or compressing the atoms that make up its crystal structure.

Caltech researchers have developed PAMs, a novel material that blends the properties of solids and liquids, making them highly adaptable for diverse applications.

These materials are inspired by chain mail but take structural complexity to new levels, thanks to advanced 3D printing.

Discovering a new type of material.

Researchers at the University of Maine have managed to 3D print an organic building material with the strength of steel.

The SM2ART Nfloor is printed as a single piece in about 30 hours, which is a third faster than building something comparable by hand according to TechXplore.

The nice thing about this set-up is that these panels can be printed in bulk off-site and get shipped to the construction area. Since there are already channels in the floor for electrical and plumbing, the only other thing that needs to be applied by hand is soundproofing and floor covering.

For the first time, researchers have measured the shape of an electron as it moves through a solid. This achievement could open a new way of looking at how electrons behave inside different materials.

Their discovery highlights many effects that could be relevant to everything from quantum information science to electronics manufacturing.

Those findings come from a team led by physicist Riccardo Comin, MIT’s Class of 1947 Career Development Associate Professor of Physics and leader of the work, in collaboration with other institutions.

Chirality refers to objects that cannot be superimposed onto their mirror images through any combination of rotations or translations, much like the distinct left and right hands of a human. In chiral crystals, the spatial arrangement of atoms confers a specific “handedness,” which—for example—influences their optical and electrical properties.

A Hamburg-Oxford team has focused on so-called antiferro-chirals, a type of non-chiral crystal reminiscent of antiferro-magnetic materials, in which magnetic moments anti-align in a staggered pattern leading to a vanishing net magnetization. An antiferro-chiral crystal is composed of equivalent amounts of left-and right-handed substructures in a unit cell, rendering it overall non-chiral.

The research team, led by Andrea Cavalleri of the Max-Planck-Institut for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter, used terahertz light to lift this balance in the non-chiral material boron phosphate (BPO4), in this way inducing finite chirality on an ultrafast time scale.

Researchers from Tokyo Metropolitan University have identified a groundbreaking new superconducting material. By combining iron, nickel, and zirconium in specific ratios, they synthesized a novel transition metal zirconide, with varying proportions of iron and nickel.

While pure iron zirconide and nickel zirconide do not exhibit superconductivity, the new mixtures demonstrate superconducting properties, forming a “dome-shaped” phase diagram characteristic of unconventional superconductors. This finding represents a significant step forward in the search for high-temperature superconducting materials that could have widespread applications.

Superconductors are already integral to advanced technologies, such as superconducting magnets in medical imaging devices, maglev trains, and power transmission cables. However, current superconductors require cooling to extremely low temperatures, typically around 4 Kelvin, which limits their practicality. Researchers are focused on discovering materials that achieve zero electrical resistance at higher temperatures, especially near the critical threshold of 77 Kelvin, where liquid nitrogen can replace liquid helium as a coolant—making the technology more accessible and cost-effective.