Tokyo eyes procuring 20% of future demand for vital magnet materials.

Dysprosium and terbium are used in high-performance magnets for EVs. © Reuters.

Japan is home to a wide variety of train stations, from tiny countryside sheds to sprawling urban complexes, stations with their own wineries and ones with giant ancient relics whose eyes glow. It’s gotten to the point where it’s really hard to be “the first” anything when it comes to train stations, but JR West has managed it with the first-ever 3D-printed station building.

This new structure is scheduled to replace the current one at Hatsushima Station on the JR Kisei Main Line in Arida City, Wakayama Prefecture. Like many relatively rural stations in Japan, the wooden structures are aging and in need of replacements.

The new building will be roughly the same size, covering 10 square meters (108 square feet) and made from a more durable reinforced concrete. The foundation and exterior of the building will be printed off-site by Osaka-based 3D-printer housing company Serendix.

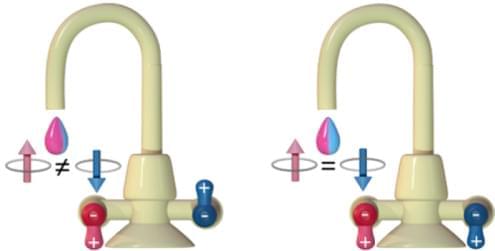

Altermagnets are arguably the hottest objects in magnetism right now (see Viewpoint: Altermagnetism Then and Now). Over the past year, researchers have delivered experimental evidence for this new type of magnet, but they have yet to harness the behavior for applications. Now three independent groups have proposed methods for electrically tuning the properties of altermagnets [1– 3]. If implemented, the findings could allow the use of altermagnets in next-generation spintronics devices.

Altermagnets can be thought of as a cross between antiferromagnets and ferromagnets. Like antiferromagnets the materials lack net magnetization—the magnetic spins of the atomic lattice are aligned in opposing directions. Like ferromagnets they have magnetically sensitive energy levels and display electronic band structures that are split into spin-up and spin-down bands. This splitting can be used to polarize an electronic current, as one spin state will flow through the material more easily. The combination of these properties could allow researchers to create spintronics devices that operate more rapidly and with greater efficiency than those currently in use, but for that, they first need a way to manipulate the spin properties of an altermagnet.

The proposed methods of the three teams (a group led by Tong Zhou of the Eastern Institute of Technology, Ningbo, China; Libor Šmejkal of the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems, Germany; and a group led by Qihang Liu of the Southern University of Science and Technology, China) all use electric fields for this switching. Controlling magnetism with electricity is particularly attractive because electric fields are much easier to manipulate and integrate into modern electronic devices than magnetic fields. Electrical tuning is potentially also faster (subnanosecond) and could use less energy, two crucial properties for the development of high-speed, low-power spintronic devices.

Scientists have unlocked a way to read magnetic orientation at record-breaking speeds using terahertz.

Terahertz radiation refers to the electromagnetic waves that occupy the frequency range between microwaves and infrared light, typically from about 0.1 to 10 terahertz (THz). This region of the electromagnetic spectrum is notable for its potential applications across a wide variety of fields, including imaging, telecommunications, and spectroscopy. Terahertz waves can penetrate non-conducting materials such as clothing, paper, and wood, making them particularly useful for security screening and non-destructive testing. In spectroscopy, they can be used to study the molecular composition of substances, as many molecules exhibit unique absorption signatures in the terahertz range.

“‘Incipient ferroelectricity’ means there’s no stable ferroelectric order at room temperature,” lead author Dipanjan Sen explains of the property that the team investigated. “Instead, there are small, scattered clusters of polar domains. It’s a more flexible structure compared to traditional ferroelectric materials.”

Typically, the “relaxor” behavior of incipient ferroelectric materials at room temperature is a drawback, making their operation less predictable and more fluid — but the team’s breakthrough was to approach it as an advantage instead, showing how it could be of use in devices like neuromorphic processors that increase machine learning and artificial intelligence performance by processing information like the neurons in the human brain.

“To test this,” co-author Mayukh Das says, “we performed a classification task using a grid of three-by-three pixel images fed into three artificial neurons. The devices were able to classify each image into different categories. This learning method could eventually be used for image identification and classification or pattern recognition. Importantly, it works at room temperature, reducing energy costs. These devices function similarly to the nervous system, acting like neurons and creating a low-cost, efficient computing system that uses a lot less energy.”

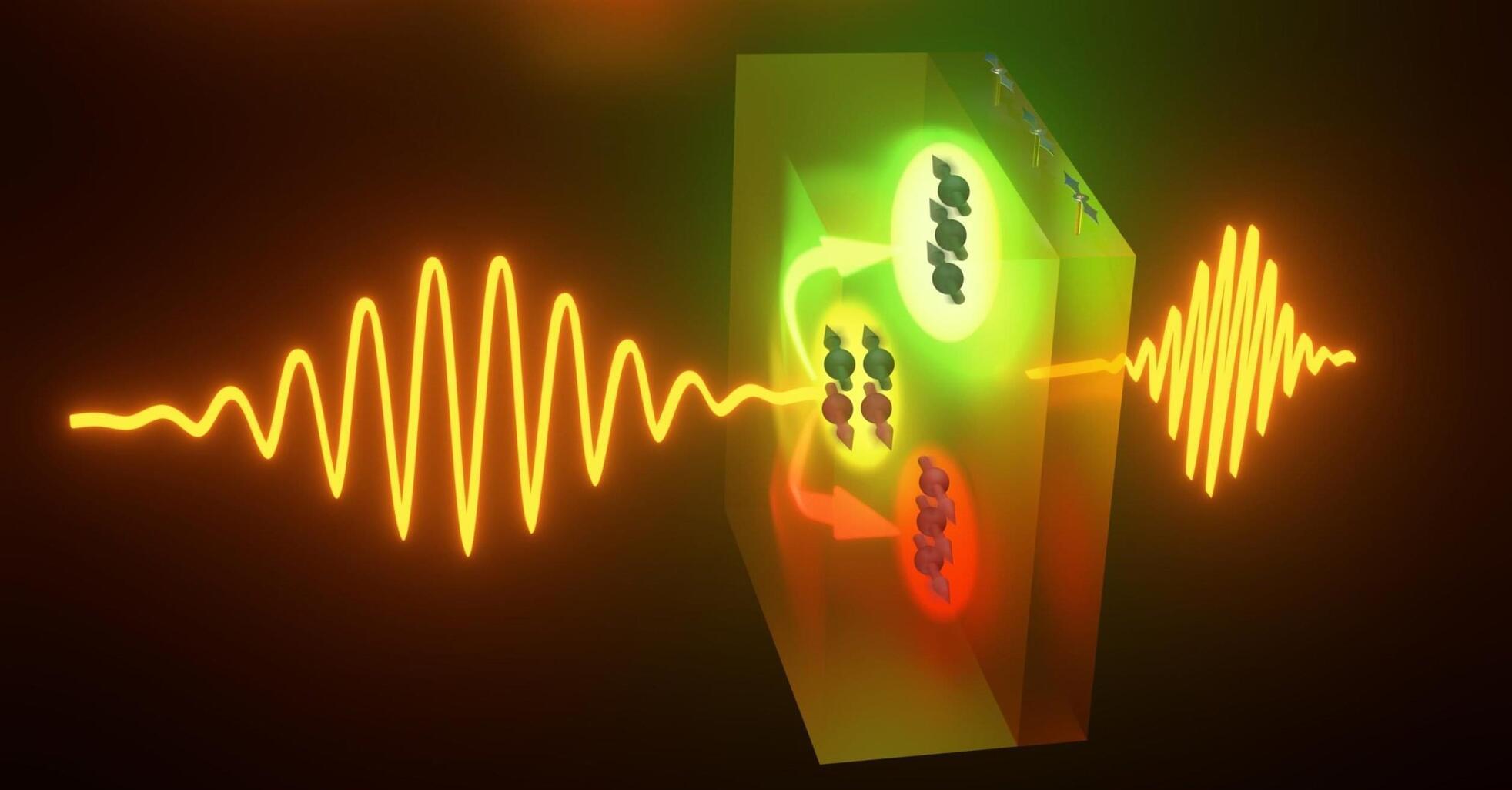

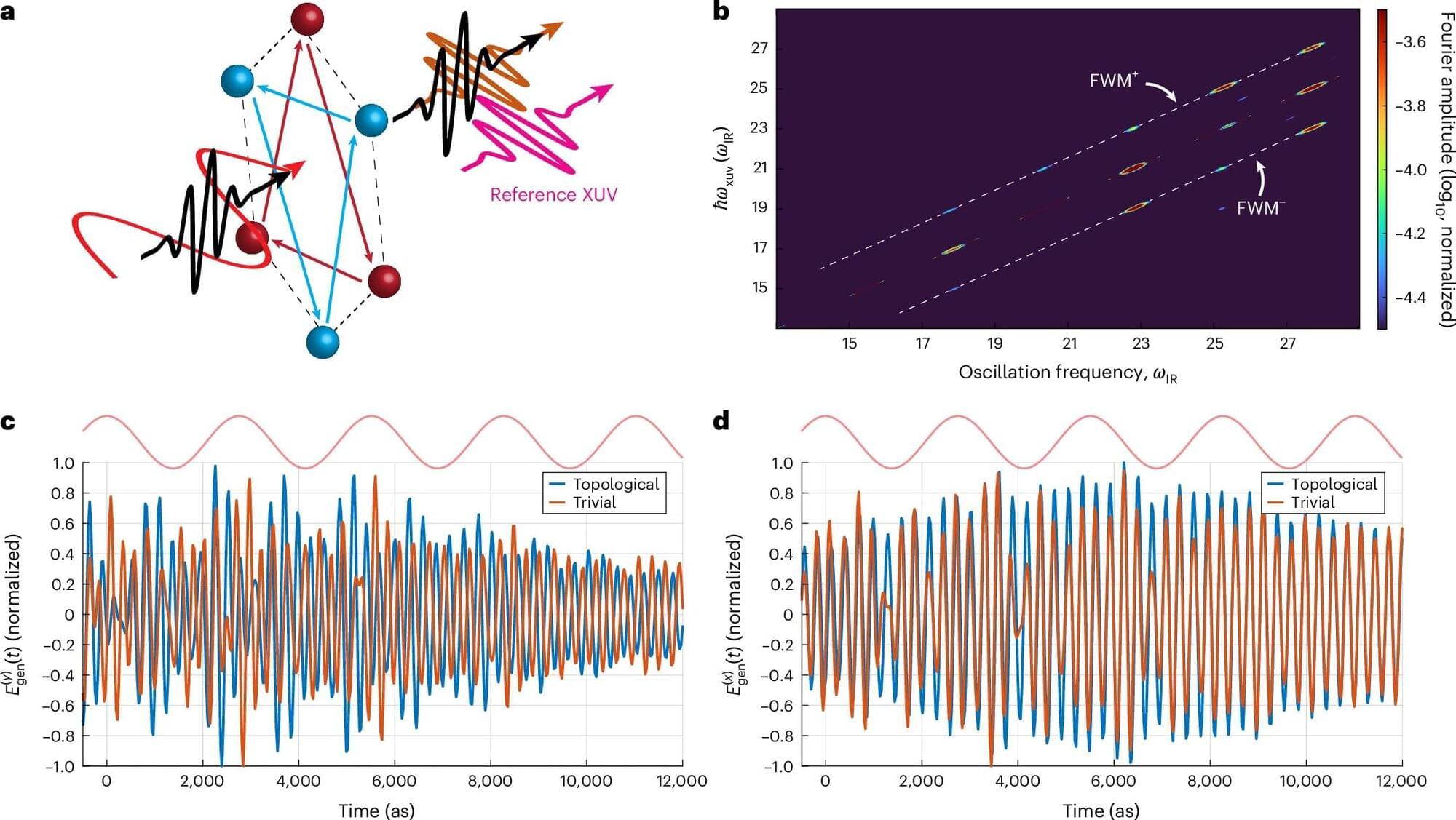

Instantly turning a material from opaque to transparent, or from a conductor to an insulator, is no longer the stuff of science fiction. For several years now, scientists have been using lasers to control the properties of matter at extremely fast rates: during one optical cycle of a light wave. But because these changes occur on the timescale of attoseconds—one-billionth of one-billionth of a second—figuring out how they unfold is extremely difficult.

In a new study published in Nature Photonics, Prof. Nirit Dudovich’s team from the Weizmann Institute of Science presents an innovative method of tracking these rapid material changes. This advance in attosecond science, the study of the fastest phenomena in nature, could have a wide variety of future applications, paving the way for ultrafast communications and computing.

If you have ever seen a rainbow, you’ve seen a practical demonstration of how light slows down and is refracted when it passes through matter, in this case, raindrops. Sunlight is composed of a broad spectrum of colors, each of which experiences a different delay as it passes through the droplets. These differences cause the colors to become separated, producing a radiant rainbow.

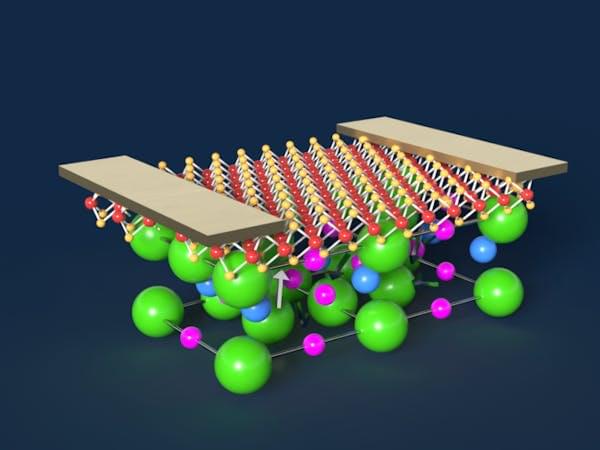

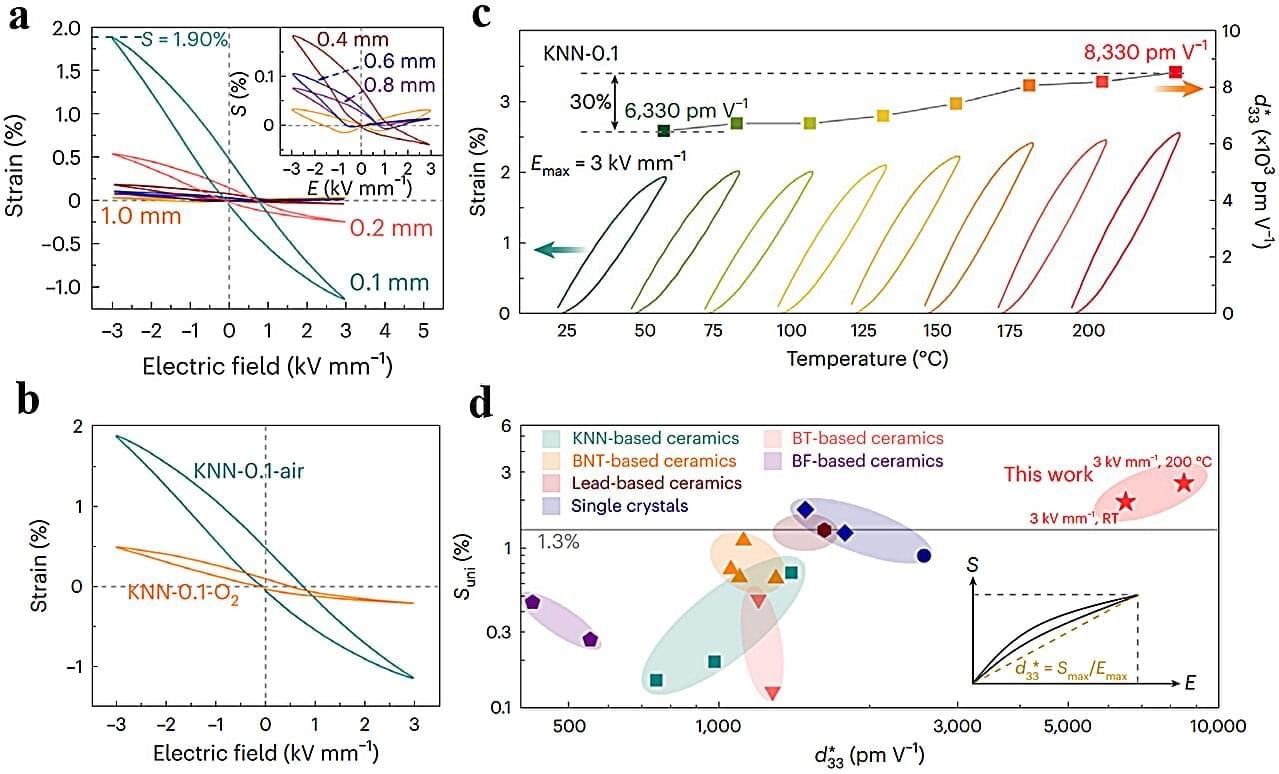

Researchers from Tsinghua University, the Beijing Institute of Technology, the University of Wollongong (Australia), and the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, have achieved an ultrahigh electrostrain of 1.9% in (K, Na)NbO3 (KNN) lead-free piezoelectric ceramics.

The breakthrough, facilitated by the electron spin resonance (ESR) spectrometer at the Steady High Magnetic Field Experimental Facility (SHMFF), marks a significant advancement in piezoelectric material performance.

The findings are published in Nature Materials.

Microsoft has reinstated the ‘Material Theme – Free’ and ‘Material Theme Icons – Free’ extensions on the Visual Studio Marketplace after finding that the obfuscated code they contained wasn’t actually malicious.

The two VSCode extensions, which count over 9 million installs, were pulled from the VSCode Marketplace in late February over security risks, and their publisher, Mattia Astorino (aka ‘equinusocio’) was banned from the platform.

“A member of the community did a deep security analysis of the extension and found multiple red flags that indicate malicious intent and reported this to us,” stated a Microsoft employee at the time.

A possible method for probing the properties of exotic particles that exist on the surfaces of an unusual type of superconductor has been theoretically proposed by two RIKEN physicists.

The paper is published in the journal Physical Review B.

When cooled to very low temperatures, two or more electrons in some solids start to behave as if they were a single particle.