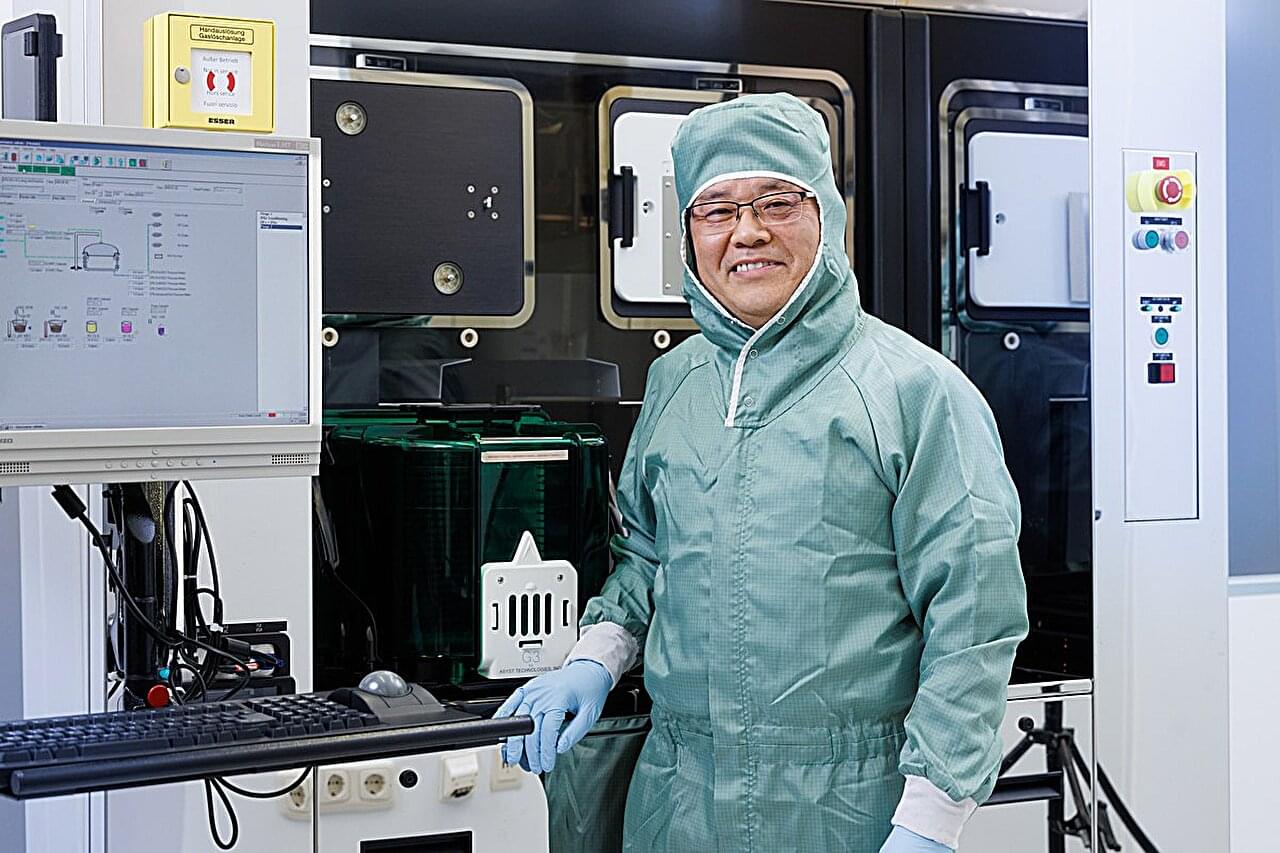

Solid-state batteries are seen as a game-changer for the future of energy storage. They can hold more power and are safer because they don’t rely on flammable materials like today’s lithium-ion batteries. Now, researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and TUMint. Energy Research have made a major breakthrough that could bring this future closer.

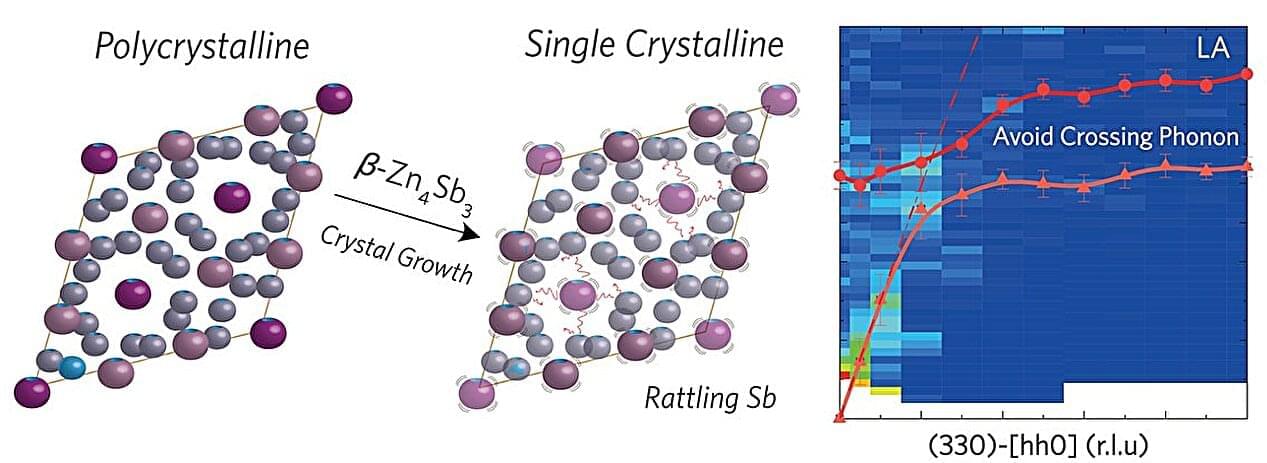

They have created a new material made from lithium, antimony, and a small amount of scandium. This material allows lithium ions to move more than 30 percent faster than any known alternative. That means record-breaking conductivity, which could lead to faster charging and more efficient batteries.

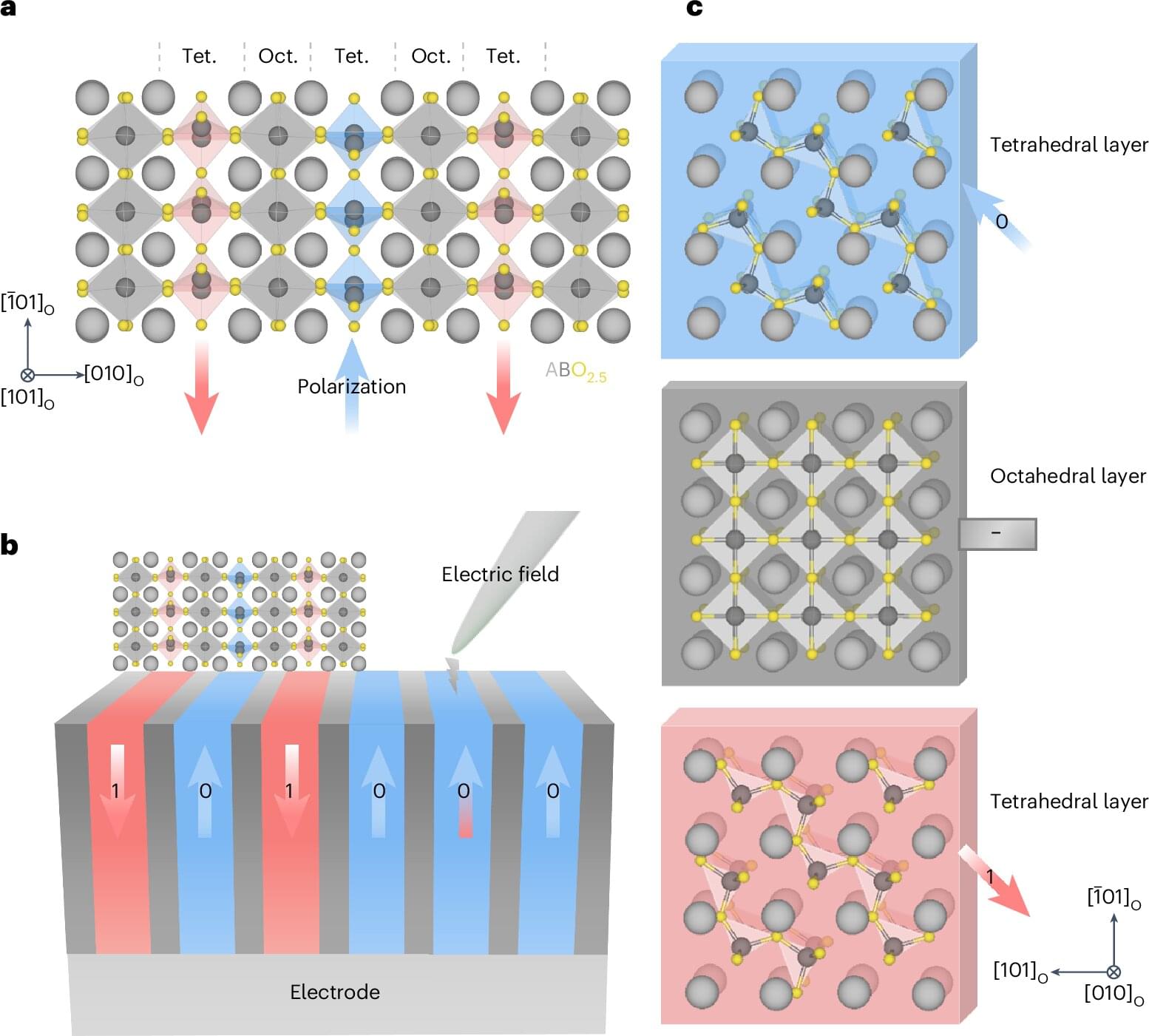

Led by Professor Thomas F. Fässler, the team discovered that swapping some of the lithium atoms for scandium atoms changes the structure of the material. This creates specific gaps, so-called vacancies, in the crystal lattice of the conductor material. These gaps help the lithium ions to move more easily and faster, resulting in a new world record for ion conductivity.