The study, “Endothelial TDP-43 Depletion Disrupts Core Blood-Brain Barrier Pathways in Neurodegeneration,” was published on March 14, 2025. The lead author, Omar Moustafa Fathy, an MD/Ph. D. candidate at the Center for Vascular Biology at UConn School of Medicine, conducted the research in the laboratory of senior author Dr. Patrick A. Murphy, associate professor and newly appointed interim director of the Center for Vascular Biology. The study was carried out in collaboration with Dr. Riqiang Yan, a leading expert in Alzheimer’s disease and neurodegeneration research.

This work provides a novel and significant exploration of how vascular dysfunction contributes to neurodegenerative diseases, exemplifying the powerful collaboration between the Center for Vascular Biology and the Department of Neuroscience. While clinical evidence has long suggested that blood-brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction plays a role in neurodegeneration, the specific contribution of endothelial cells remained unclear. The BBB serves as a critical protective barrier, shielding the brain from circulating factors that could cause inflammation and dysfunction. Though multiple cell types contribute to its function, endothelial cells—the inner lining of blood vessels—are its principal component.

“It is often said in the field that ‘we are only as old as our arteries’. Across diseases we are learning the importance of the endothelium. I had no doubt the same would be true in neurodegeneration, but seeing what these cells were doing was a critical first step,” says Murphy.

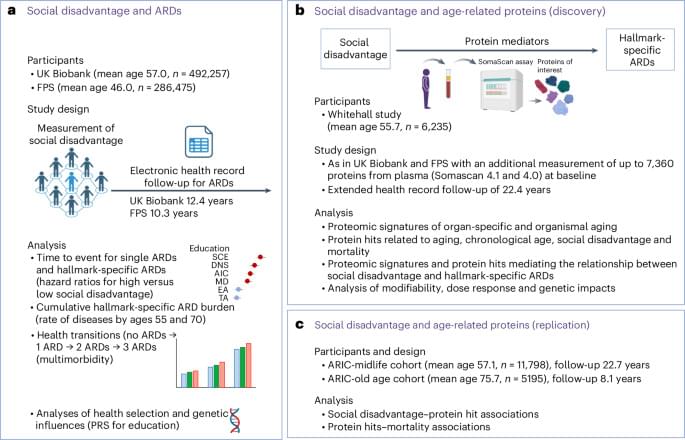

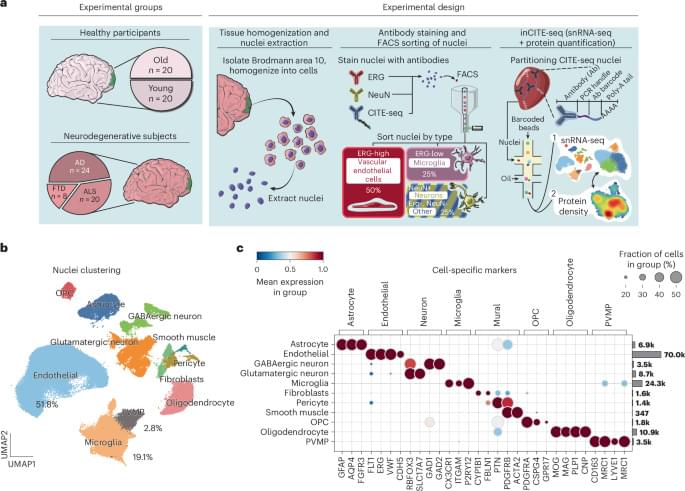

Omar, Murphy, and their team tackled a key challenge: endothelial cells are rare and difficult to isolate from tissues, making it even harder to analyze the molecular pathways involved in neurodegeneration.

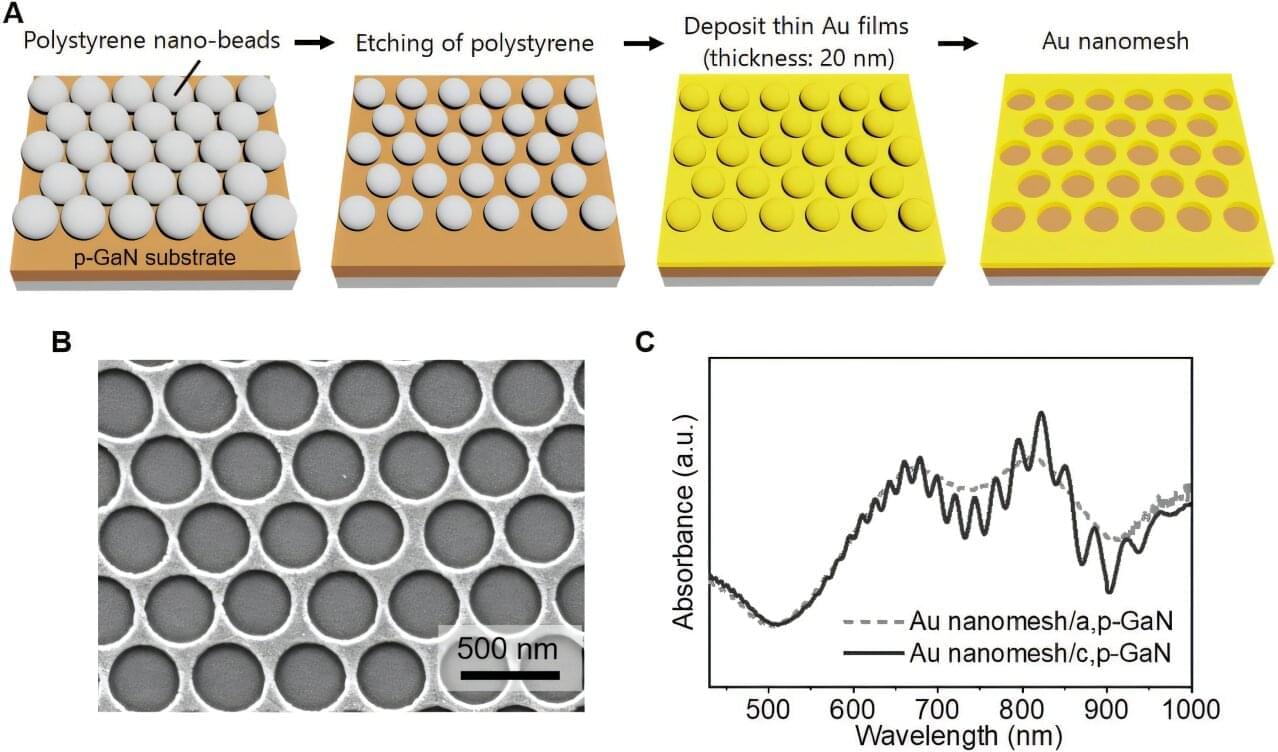

To overcome this, they developed an innovative approach to enrich these cells from frozen tissues stored in a large NIH-sponsored biobank. They then applied inCITE-seq, a cutting-edge method that enables direct measurement of protein-level signaling responses in single cells—marking its first-ever use in human tissues.

This breakthrough led to a striking discovery: endothelial cells from three different neurodegenerative diseases—Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD)—shared fundamental similarities that set them apart from the endothelium in healthy aging. A key finding was the depletion of TDP-43, an RNA-binding protein genetically linked to ALS-FTD and commonly disrupted in AD. Until now, research has focused primarily on neurons, but this study highlights a previously unrecognized dysfunction in endothelial cells.

“It’s easy to think of blood vessels as passive pipelines, but our findings challenge that view,” says Omar. “Across multiple neurodegenerative diseases, we see strikingly similar vascular changes, suggesting that the vasculature isn’t just collateral damage—it’s actively shaping disease progression. Recognizing these commonalities opens the door to new therapeutic possibilities that target the vasculature itself.”