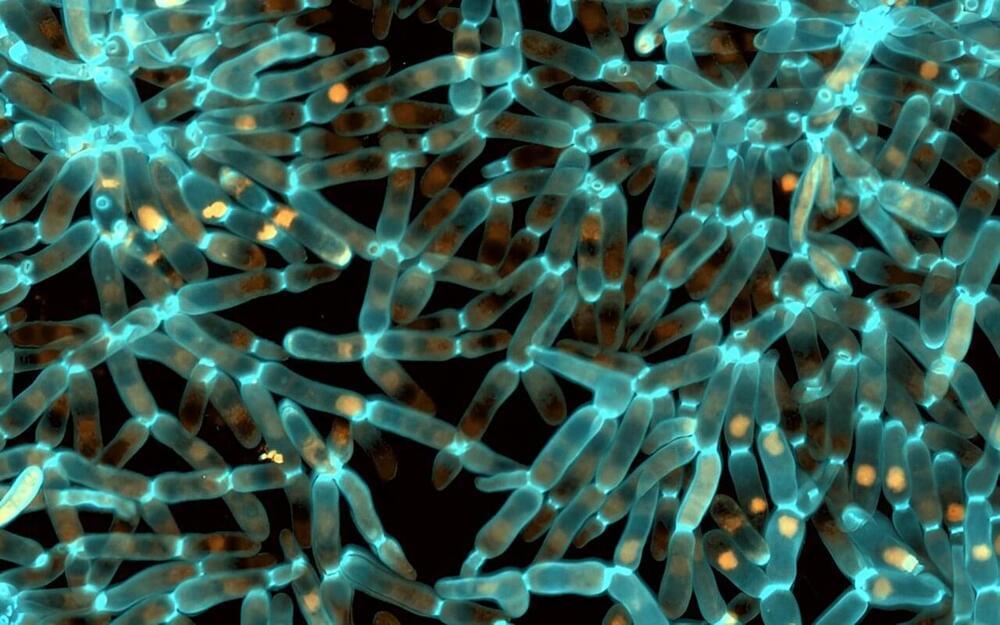

Researchers have discovered a mechanism steering the evolution of multicellular life. They identify how altered protein folding drives multicellular evolution.

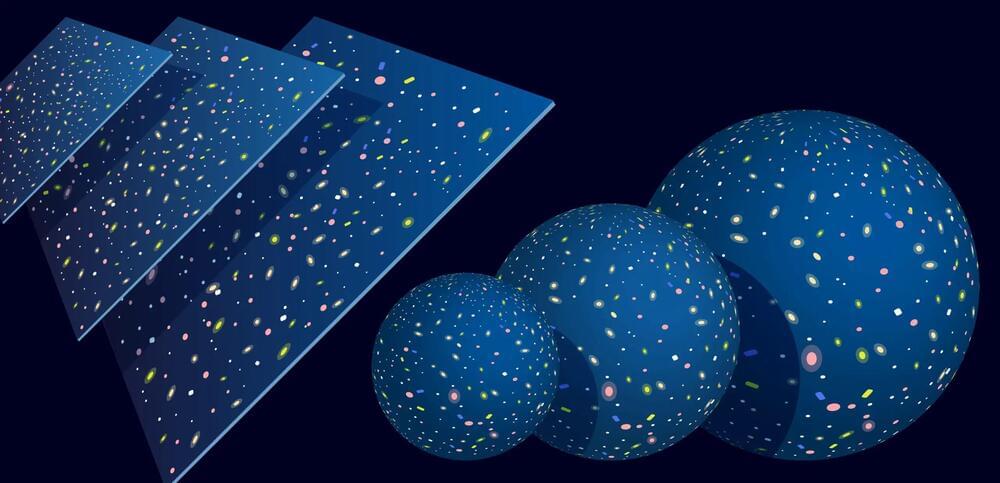

In a new study led by researchers from the University of Helsinki and the Georgia Institute of Technology, scientists turned to a tool called experimental evolution. In the ongoing Multicellularity Long Term Evolution Experiment (MuLTEE), laboratory yeast are evolving novel multicellular functions, enabling researchers to investigate how they arise.

The study, published in Science Advances, puts the spotlight on the regulation of proteins in understanding evolution.