Since 1975, Roxanne Meadows has worked with renowned futurist Jacque Fresco to develop and promote The Venus Project. The function of this project is to find alternative solutions to the many problems that confront the world today. She participated in the exterior and interior design and construction of the buildings of The Venus Project’s 21-acre research and planning center.

Category: evolution – Page 116

For transhumanists, the possibilities of human interconnectivity via technology is only the beginning of how people may eventually transcend the limitations of their bodies. Photographer David Vintiner and art director Gem Fletcher set out to meet the innovators, artists, and dreamers within the transhumanism movement who are pushing the boundaries of their biology to become something more than human. Their project I Want to Believe consists of three chapters — the first touching on wearable technology, the second on individuals who have made permanent changes to their bodies, and the last on how some transhumanists plan to transcend the human condition.

“Science and human advancement has always been propelled forward by the people who do things differently and those who are not afraid to break the rules.”

Scientists in Argentina decipher complete genome of SARS-Cov-2. Work by ANLIS-Malbrán Institute specialists will allow experts to follow evolution of virus in Argentina, ensure quality of diagnosis and contribute to development of vaccine.

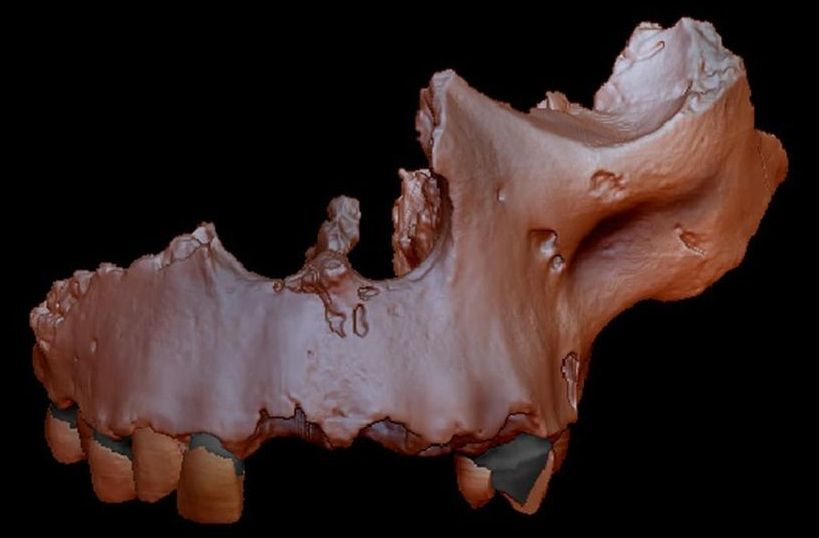

It’s hard to piece together the full history of human evolution from piles of old bones. But now, scientists have made use of a new method to study proteins in dental enamel of an 800,000-year-old human species, helping place it in the family tree.

Although Homo sapiens is the only human species still alive today, the road to get here is paved with extinct relatives. And untangling how they’re all related to each other is a task that scientists continue to wrestle with. The timeline is usually determined through various dating processes, both on the bones themselves and the sediment layers they’re found in. Relationships between species are then determined from this timeline, and by examining the structures and features of the bones to track the progress of evolution.

For the new study, researchers at the University of Copenhagen have used a new tool called palaeoproteomics to get a more precise picture. This involves sequencing proteins from ancient remains, and it works on samples that are far too old to have intact DNA. In this case, the team applied it to the 800,000-year-old teeth of a mysterious, archaic human species called Homo antecessor.

Since its beginnings, quantum mechanics hasn’t ceased to amaze us with its peculiarity, so difficult to understand. Why does one particle seem to pass through two slits simultaneously? Why, instead of specific predictions, can we only talk about evolution of probabilities? According to theorists from universities in Warsaw and Oxford, the most important features of the quantum world may result from the special theory of relativity, which until now seemed to have little to do with quantum mechanics.

Since the arrival of quantum mechanics and the theory of relativity, physicists have lost sleep over the incompatibility of these three concepts (three, since there are two theories of relativity: special and general). It has commonly been accepted that it is the description of quantum mechanics that is the more fundamental and that the theory of relativity that will have to be adjusted to it. Dr. Andrzej Dragan from the Faculty of Physics, University of Warsaw (FUW) and Prof. Artur Ekert from the University of Oxford (UO) have just presented their reasoning leading to a different conclusion. In the article “The Quantum Principle of Relativity,” published in the New Journal of Physics, they prove that the features of quantum mechanics determining its uniqueness and its non-intuitive exoticism—accepted, what’s more, on faith (as axioms)—can be explained within the framework of the special theory of relativity. One only has to decide on a certain rather unorthodox step.

Albert Einstein based the special theory of relativity on two postulates. The first is known as the Galilean principle of relativity (which, please note, is a special case of the Copernican principle). This states that physics is the same in every inertial system (i.e., one that is either at rest or in a steady straight line motion). The second postulate, formulated on the result of the famous Michelson-Morley experiment, imposed the requirement of a constant velocity of light in every reference system.

IM’s mission is to offer the most reliable and relevant information on radical life extension and human enhancement.

IM’s is published monthly and features articles and interviews by distinguished scholars, scientists, philosophers, artists, designers, bloggers, speakers, and entrepreneurs.

Forget the simple out-of-Africa idea of how humans evolved. A huge array of fossils and genome studies has completely rewritten the story of how we came into being.

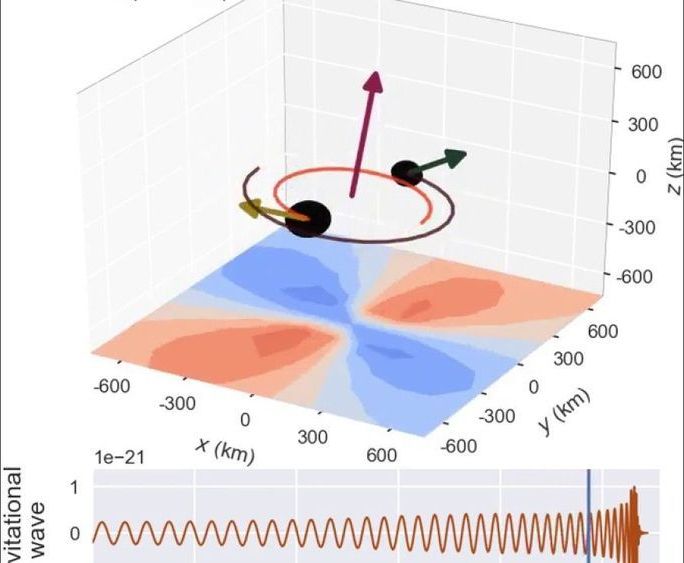

Shoot a rifle, and the recoil might knock you backward. Merge two black holes in a binary system, and the loss of momentum gives a similar recoil—a “kick”—to the merged black hole.

“For some binaries, the kick can reach up to 5000 kilometers a second, which is larger than the escape velocity of most galaxies,” said Vijay Varma, an astrophysicist at the California Institute of Technology and an incoming inaugural Klarman Fellow at Cornell University’s College of Arts & Sciences.

Varma and his fellow researchers have developed a new method using gravitational wave measurements to predict when a final black hole will remain in its host galaxy and when it will be ejected. Such measurements could provide a crucial missing piece of the puzzle behind the origin of heavy black holes, said Varma, as well as offer insights into galaxy evolution and tests of general relativity. He is lead author of “Extracting the Gravitational Recoil from Black Hole Merger Signals,” published March 13 in Physical Review Letters and co-authored with Maximiliano Isi and Sylvia Biscoveanu of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

There are endless viruses in our midst, made either of RNA or DNA viruses, which exist in much greater abundance around the planet, are capable of causing systemic diseases that are endemic, latent, and persistent—like the herpes viruses (which includes chicken pox), hepatitis B, and the papilloma viruses that cause cancer. “DNA viruses are the ones that live with us and stay with us,” Denison said. “They’re lifelong.” Retroviruses, like H.I.V., have RNA in their genomes but behave like DNA viruses in the host. RNA viruses, on the other hand, have simpler structures and mutate rapidly. “Viruses mutate quickly, and they can retain advantageous traits,” Epstein told me. “A virus that’s more promiscuous, more generalist, that can inhabit and propagate in lots of other hosts ultimately has a better chance of surviving.” They also tend to cause epidemics—such as measles, Ebola, Zika, and a raft of respiratory infections, including influenza and coronaviruses. Paul Turner, a Rachel Carson professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Yale University, told me, “They’re the ones that surprise us the most and do the most damage.”

Scientists discovered the coronavirus family in the nineteen-fifties, while peering through early electron microscopes at samples taken from chickens suffering from infectious bronchitis. The coronavirus’s RNA, its genetic code, is swathed in three different kinds of proteins, one of which decorates the virus’s surface with mushroom-like spikes, giving the virus the eponymous appearance of a crown. Scientists found other coronaviruses that caused disease in pigs and cows, and then, in the mid-nineteen-sixties, two more that caused a common cold in people. (Later, widespread screening identified two more human coronaviruses, responsible for colds.) These four common-cold viruses might have come, long ago, from animals, but they are now entirely human viruses, responsible for fifteen to thirty per cent of the seasonal colds in a given year. We are their natural reservoir, just as bats are the natural reservoir for hundreds of other coronaviruses. But, since they did not seem to cause severe disease, they were mostly ignored. In 2003, a conference for nidovirales (the taxonomic order under which coronaviruses fall) was nearly cancelled, due to lack of interest. Then SARS emerged, leaping from bats to civets to people. The conference sold out.

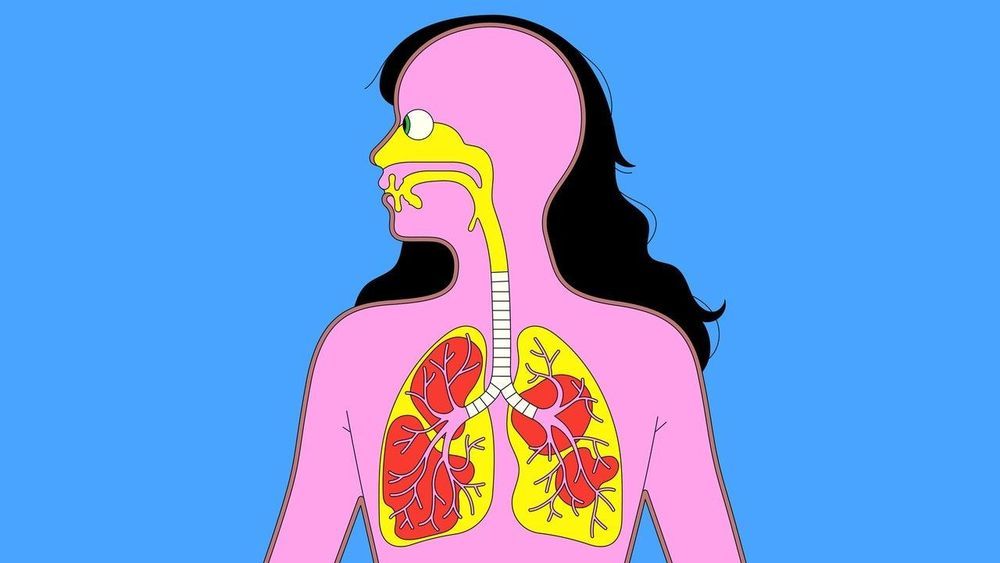

SARS is closely related to the new virus we currently face. Whereas common-cold coronaviruses tend to infect only the upper respiratory tract (mainly the nose and throat), making them highly contagious, SARS primarily infects the lower respiratory system (the lungs), and therefore causes a much more lethal disease, with a fatality rate of approximately ten per cent. (MERS, which emerged in Saudi Arabia, in 2012, and was transmitted from bats to camels to people, also caused severe disease in the lower respiratory system, with a thirty-seven per cent fatality rate.) SARS-CoV-2 behaves like a monstrous mutant hybrid of all the human coronaviruses that came before it. It can infect and replicate throughout our airways. “That’s why it is so bad,” Stanley Perlman, a professor of microbiology and immunology who has been studying coronaviruses for more than three decades, told me. “It has the lower-respiratory severity of SARS and MERS coronaviruses, and the transmissibility of cold coronaviruses.”

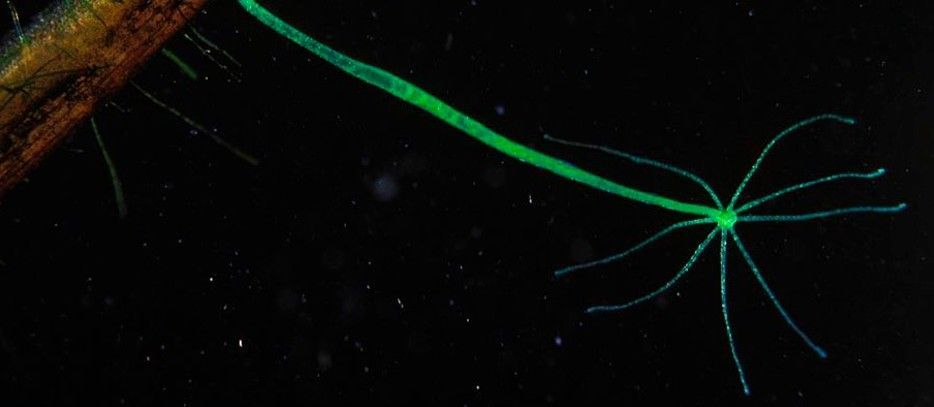

The hydra is named after the serpent monster from Greek myth, which regrows two heads each time one is cut off. But freshwater hydras have an even more impressive regenerating ability: an entire hydra can regrow from a small piece of tissue in only a few days.

Biologists are particularly excited by this ability, since many of the networks involved in the healing process developed early in the process of evolution, meaning that they are shared among many animals, including humans.

“In other organisms, like humans, once our brain is injured, we have difficulty recovering because the brain lacks the kind of regenerative abilities we see in hydra,” said researcher Abby Primack.