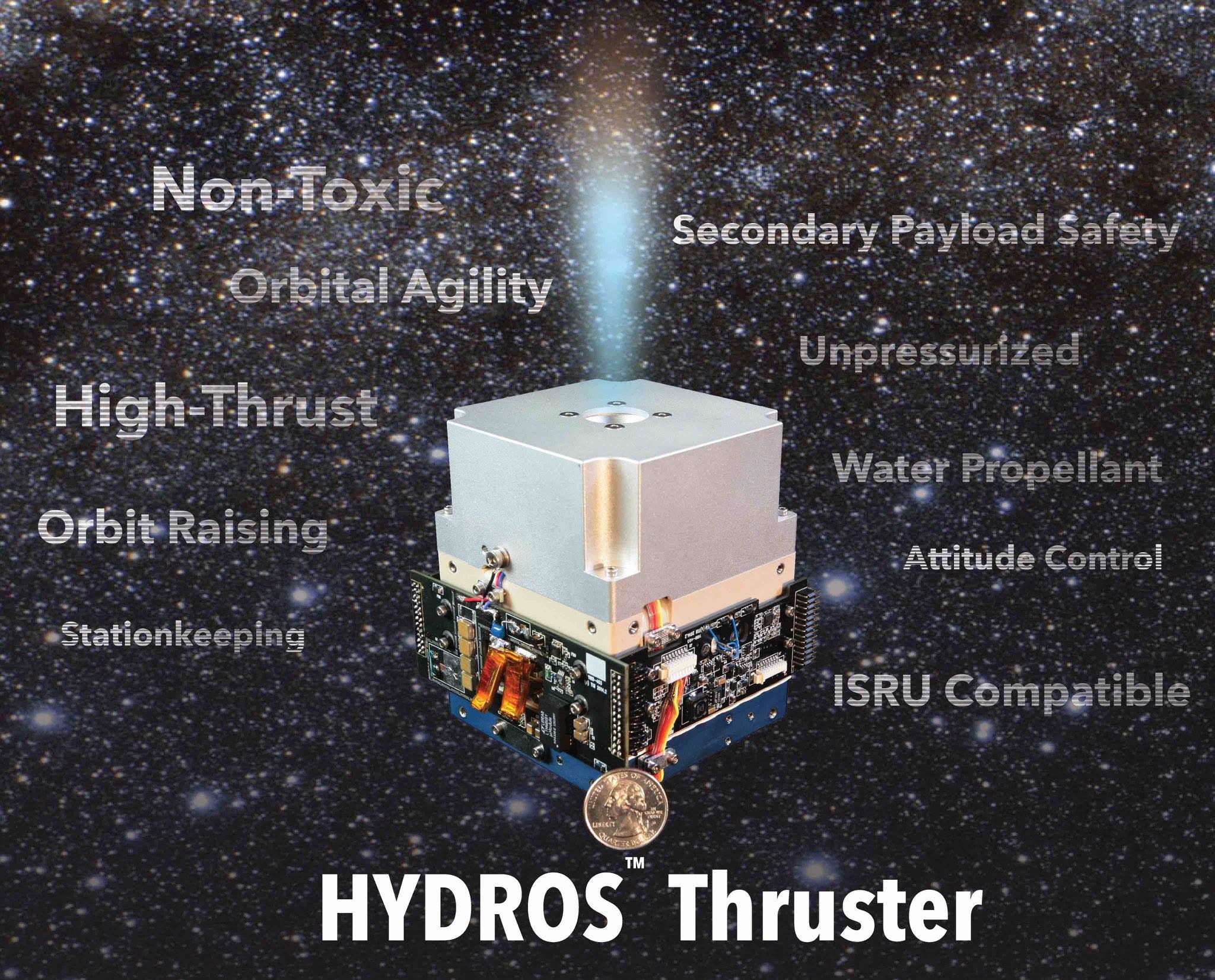

Tethers Unlimited, Inc. (TUI) announced that it has signed a Public-Private Partnership with NASA to deliver a HYDROS™ propulsion system for a CubeSat mission. Concurrently, TUI has signed an associated contract to provide three HYDROS thrusters sized for Millennium Space Systems’ (MSS) ALTAIR™ class microsatellites to support three different flight missions. Total contract value for the two efforts is $2.2M.

The HYDROS propulsion system uses in-space electrolysis of water to generate hydrogen and oxygen gas, which it then burns in a bipropellant thruster. This water-electrolysis method allows small satellites to carry a propellant that is non-explosive, non-toxic, and unpressurized. The hydrogen and oxygen generated on-orbit will enable high-thrust and high-fuel-efficiency propulsion so these small satellites can perform missions requiring orbital agility and long-duration station-keeping.

The partnership with NASA is a cost-sharing program funded under NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate’s “Utilizing Public-Private Partnerships to Advance Tipping Point Technologies” Program. In this effort, TUI will conduct lifetime and environmental testing of prototypes of HYDROS systems sized for CubeSats and microsatellites and then deliver a flight unit HYDROS thruster intended for testing on a CubeSat mission as part of NASA’s Pathfinder Technology Demonstration Program, at Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California.

The purchase of HYDROS thrusters by MSS represents a significant commercial customer investment that will enable the HYDROS Public-Private Partnership to develop and deliver a transformative propulsion technology meeting needs for both NASA and commercial small satellite endeavors.

“We are honored to have the opportunity to partner with NASA and Millennium Space Systems to demonstrate this revolutionary thruster technology,” said Dr. Rob Hoyt, TUI’s CEO and Chief Scientist. “Traditionally it has been very difficult to launch small satellites with propulsion capabilities due to the risks that standard propellants such as hydrazine pose to the launch vehicle’s primary payload. HYDROS will enable highly-maneuverable satellites to launch as secondary payloads without posing a significant risk to primary payloads. In the future, when asteroid and lunar mining efforts begin to provide in-situ resources, the HYDROS technology will enable use of the water ice available on asteroids and the Moon to propel the spacecraft, equipment, and resources needed for a robust in-space economy.”