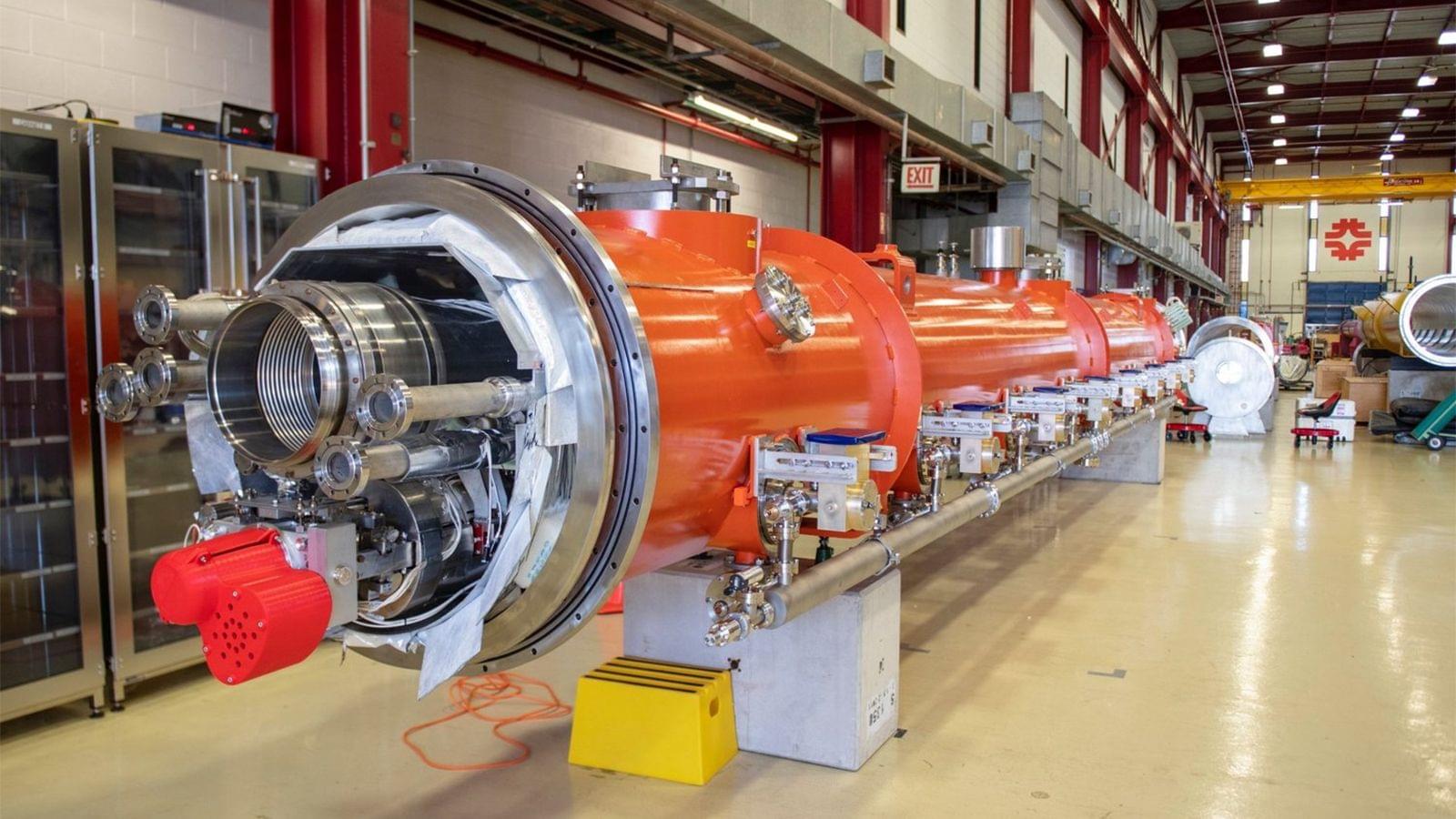

XLight, a U.S.-based startup developing an EUV light source based on a particle accelerator, on Tuesday signed a Letter of Intent (LOI) with the U.S. Department of Commerce for $150 million in proposed federal incentives under the CHIPS and Science Act. xLight came out of the blue earlier this year when it hired Pat Gelsinger, former chief executive of Intel, as executive chairman. The money, if awarded, will be used to bring xLight’s free-electron laser (FEL) based light source closer to reality once it is built in Albany and its viability is proven in practice.

“With the support from the [Department of] Commerce, our investors, and development partners, xLight is building its first free-electron laser system at the Albany Nanotech Complex, where the world’s best lithography capabilities will enable the research and development that will define the future of chip manufacturing,” said Nicholas Kelez, CEO and CTO of xLight.