The manufacturing and deployment of hybrid and electric vehicles is on the rise, contributing to ongoing efforts to decarbonize the transport industry. While cars and smaller vehicles can be powered using lithium batteries, electrifying heavy-duty vehicles, such as trucks and large buses, has so far proved much more challenging.

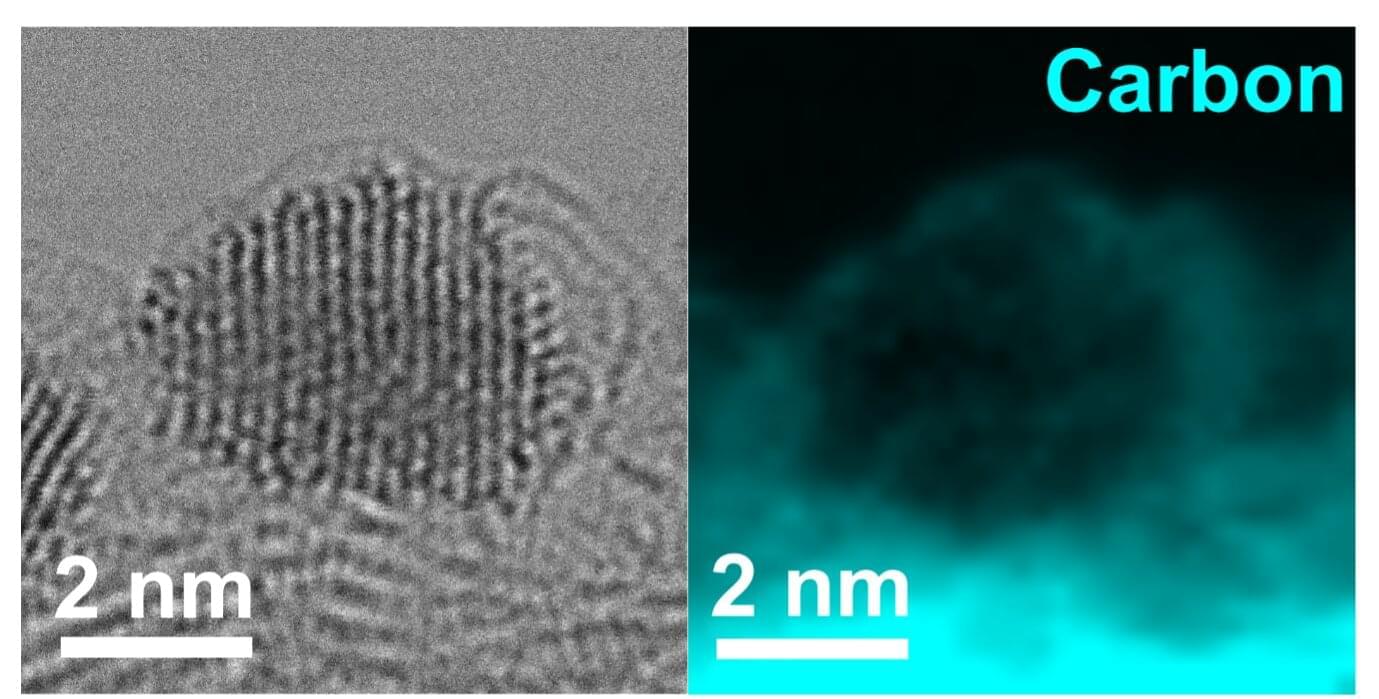

Fuel cells, devices that generate electricity via chemical reactions, are promising solutions for powering heavy-duty vehicles. Most of the fuel cells employed so far are so-called proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs), cells that generate electricity via the reaction of hydrogen and oxygen, conducting protons from their anode to their cathode utilizing a solid polymer membrane.

Despite their potential, many existing fuel cells have limited lifetimes and efficiencies. These limitations have so far hindered their widespread adoption in the manufacturing of electric or hybrid trucks, buses and other heavy-truck vehicles.