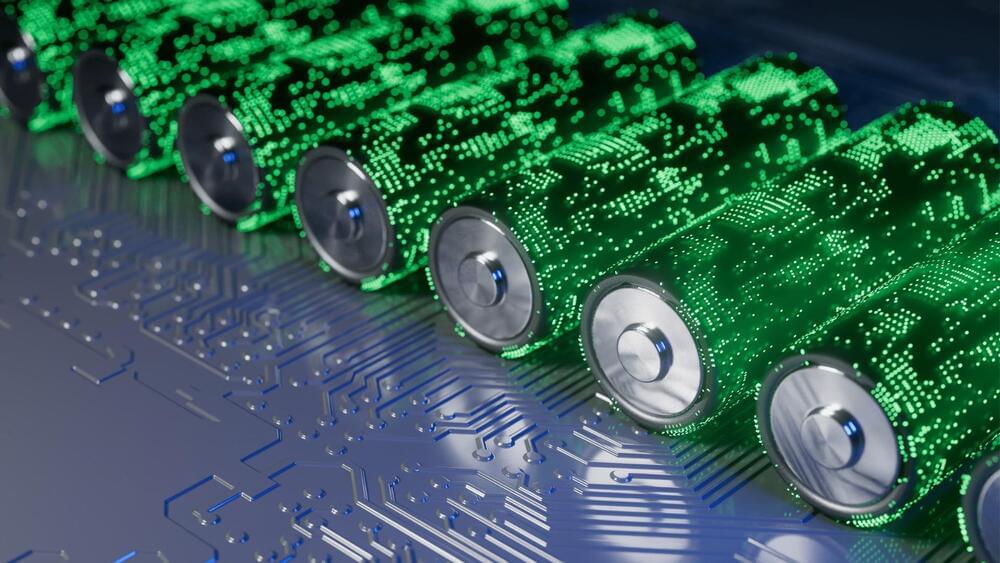

This article is part of a series of pieces on advances in sustainable battery technologies that Physics Magazine is publishing to celebrate Earth Week 2024. See also: Q&A: Electrochemists Wanted for Vocational Degrees; Research News: Lithium-Ion “Traffic Jam” Behind Reduced Battery Performance; Q&A: The Path to Making Batteries Green; News Feature: Sodium Batteries as a Greener Lithium Substitute.

Since the first prototype made its debut in 2000, rechargeable magnesium batteries have continued to be both technologically attractive and commercially out of reach. The attraction arises from magnesium’s advantages over lithium: it is 1,000 times more abundant in Earth’s crust and is chemically less hazardous. The unrealized commercialization is largely down to the difficulty in identifying a material to serve as an effective and robust cathode. Tomoya Kawaguchi of Tohoku University in Japan and his collaborators may now have solved that problem through their demonstration of a material that satisfies one of the most important requirements of a good cathode: it can reversibly accept and release ions over repeated charging cycles [1].

The discharge of an electrochemical battery releases electrons that flow through the connected circuit. It also releases ions from the battery’s anode that flow through the battery’s electrolyte, in the opposite direction to the electrons, and then lodge in the cathode. The flows reverse directions during recharging. In a lithium-ion battery, the cathode is made from a lithium oxide and takes the form of either a layered material or a crystalline solid known as a spinel.