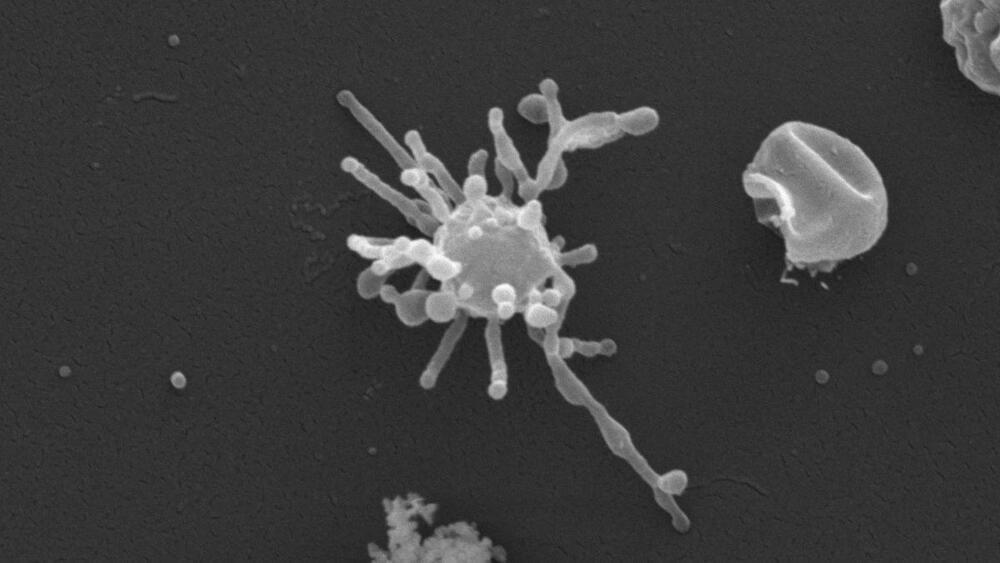

Scientists successfully grew Asgard archaea in the lab and took detailed images.

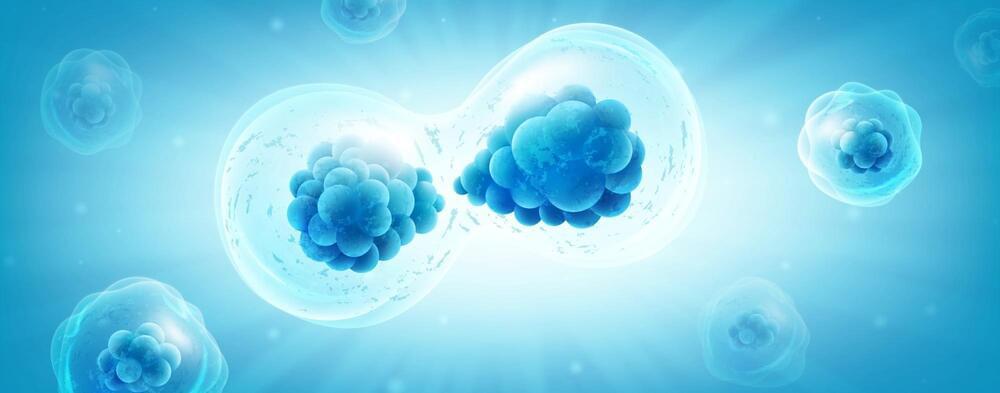

In a recent study published in Cell Reports, researchers performed a genomic analysis to investigate the origination of human microproteins of biological importance.

Studies have reported that sORFs (small open reading frames) encode functional microproteins essential for several biological processes. However, the origination and conservation of such microproteins have not been well-characterized. Genomic analysis of microproteins could deepen understanding of human genomic characteristics critical for functionality.

A Kent team, led by Professors Ben Goult and Jen Hiscock, has created and patented a ground-breaking new shock-absorbing material that could revolutionise both the defence and planetary science sectors.

This novel protein-based family of materials, named TSAM (Talin Shock Absorbing Materials), represents the first known example of a SynBio (or synthetic biology) material capable of absorbing supersonic projectile impacts. This opens the door for the development of next-generation bullet-proof armour and projectile capture materials to enable the study of hypervelocity impacts in space and the upper atmosphere (astrophysics).

Professor Ben Goult explained: ‘Our work on the protein talin, which is the cells natural shock absorber, has shown that this molecule contains a series of binary switch domains which open under tension and refold again once tension drops. This response to force gives talin its molecular shock absorbing properties, protecting our cells from the effects of large force changes. When we polymerised talin into a TSAM, we found the shock absorbing properties of talin monomers imparted the material with incredible properties.’

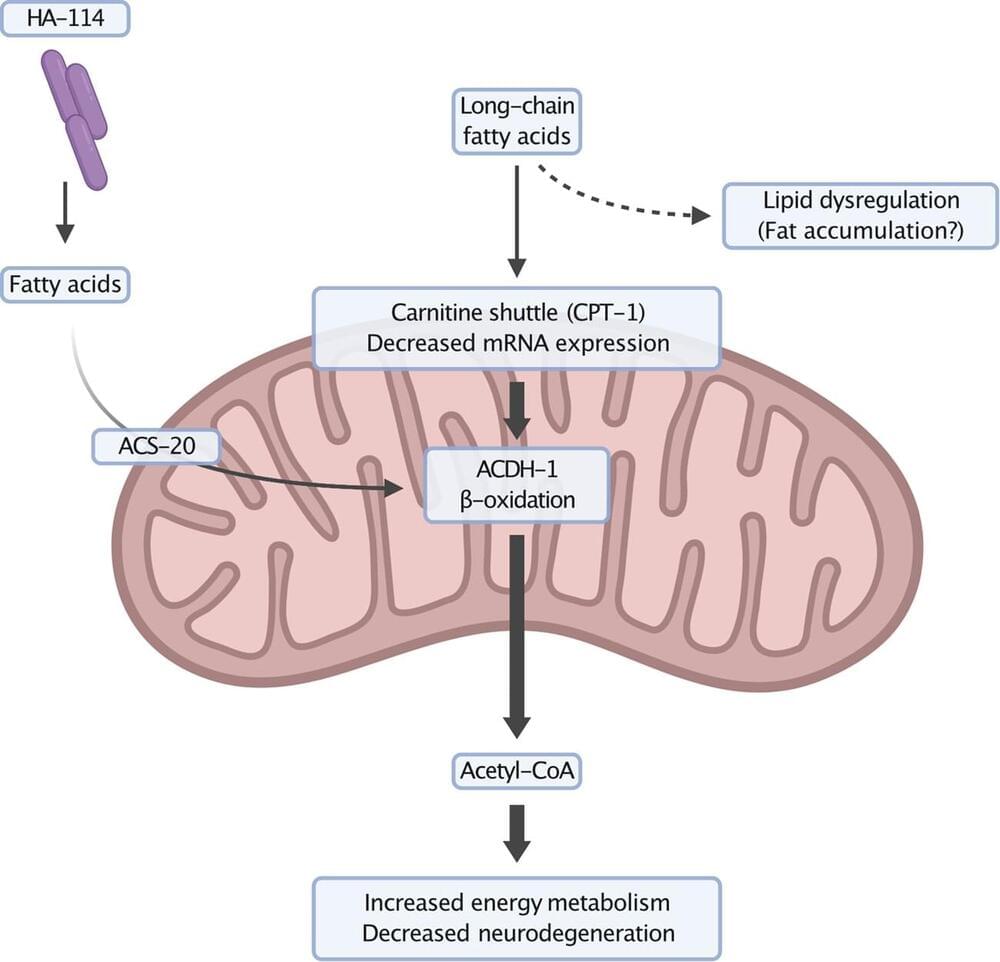

A probiotic bacterium called Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus HA-114 prevents neurodegeneration in the C. elegans worm, an animal model used to study amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

That’s the finding of a new study at Canada’s CHUM Research Center (CRCHUM) led by Université de Montréal neuroscience professor Alex Parker and published in the journal Communications Biology.

He and his team suggest that the disruption of lipid metabolism contributes to this cerebral degeneration, and show that the neuroprotection provided by HA-114, a non-commercial probiotic, is unique compared to other strains of the same bacterial family tested.

How ethical would aliens be?

Ethics derived from biological evolution can be harsh — parasitism, invasiveness, and survival at all costs. Ethics derived from human culture is far more benevolent. Would alien ethics be based more on biology or culture? Let’s hope the latter.

Posted on big think, direct weblink at.

Posted on Big Think.

As they suggest, Denisova 11 was not an isolated case but rather a hint of a more general introgression process.

This study was the first to use deep learning technologies to inspect human evolution. In the future, it’s expected to become more common in fields such as biology, genomics and evolution.

Extract from “Cell Intelligence in Physiological & Morphological Spaces”, kindly contributed by Michael Levin in SEMF’s 2022 Spacious Spatiality.

Full talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jLiHLDrOTW8

MICHAEL LEVIN

Department of Biology, Tufts University: https://as.tufts.edu/biology.

Tufts University profile: https://ase.tufts.edu/biology/labs/levin/

Wyss Institute profile: https://wyss.harvard.edu/team/associate-faculty/michael-levin-ph-d/

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Levin_(biologist)

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=luouyakAAAAJ

Twitter: https://twitter.com/drmichaellevin.

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/michael-levin-b0983a6/

SEMF NETWORKS

Website: https://semf.org.es.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/semf_nexus.

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/semf-nexus.

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/semf.nexus.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/semf.nexus

This video explores the timelapse of artificial intelligence from 2030 to 10,000A.D.+. Watch this next video about Super Intelligent AI and why it will be unstoppable: https://youtu.be/xPvo9YYHTjE

► Support This Channel: https://www.patreon.com/futurebusinesstech.

► Udacity: Up To 75% Off All Courses (Biggest Discount Ever): https://bit.ly/3j9pIRZ

► Brilliant: Learn Science And Math Interactively (20% Off): https://bit.ly/3HAznLL

► Jasper AI: Write 5x Faster With Artificial Intelligence: https://bit.ly/3MIPSYp.

SOURCES:

• https://www.futuretimeline.net.

• The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology (Ray Kurzweil): https://amzn.to/3ftOhXI

• The Future of Humanity (Michio Kaku): https://amzn.to/3Gz8ffA

• Physics of the Future (Michio Kaku): https://amzn.to/33NP7f7

• Physics of the Impossible (Michio Kaku): https://amzn.to/3wSBR4D

• AI 2041: 10 Visions of Our Future (Kai-Fu Lee & Chen Qiufan): https://amzn.to/3bxWat6

Official Discord Server: https://discord.gg/R8cYEWpCzK

💡 Future Business Tech explores the future of technology and the world.

Examples of topics I cover include:

• Artificial Intelligence.

• Genetic Engineering.

• Virtual and Augmented Reality.

• Space Exploration.

• Science Fiction.

SUBSCRIBE: https://bit.ly/3geLDGO

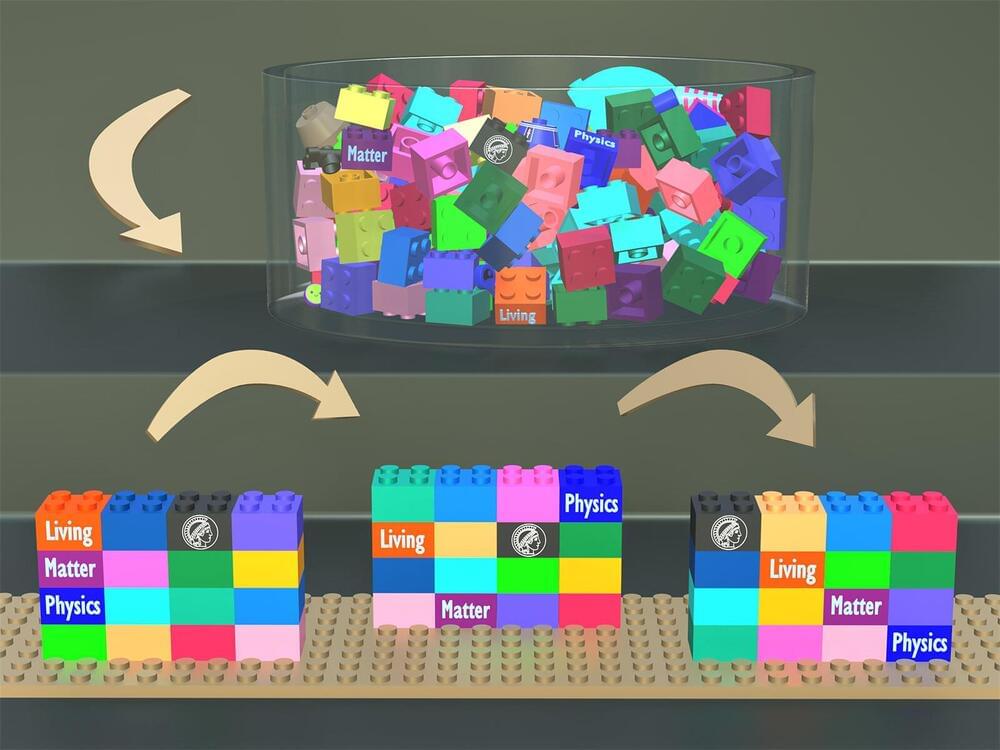

Structures made out of building blocks can shift their shape and autonomously self-organize to a new configuration. The physicists Saeed Osat and Ramin Golestanian from the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organization (MPI-DS) revealed this mechanism which may be used to actively manipulate molecular organization. A seed of the novel desired configuration is sufficient to trigger reorganization.

This principle can be applied on to biological building blocks which are constantly recycled to form new structures in living systems.

The concept of remodeling is familiar to most people: those who have ever played with Lego bricks know that many combinations and structures possible from the same components.

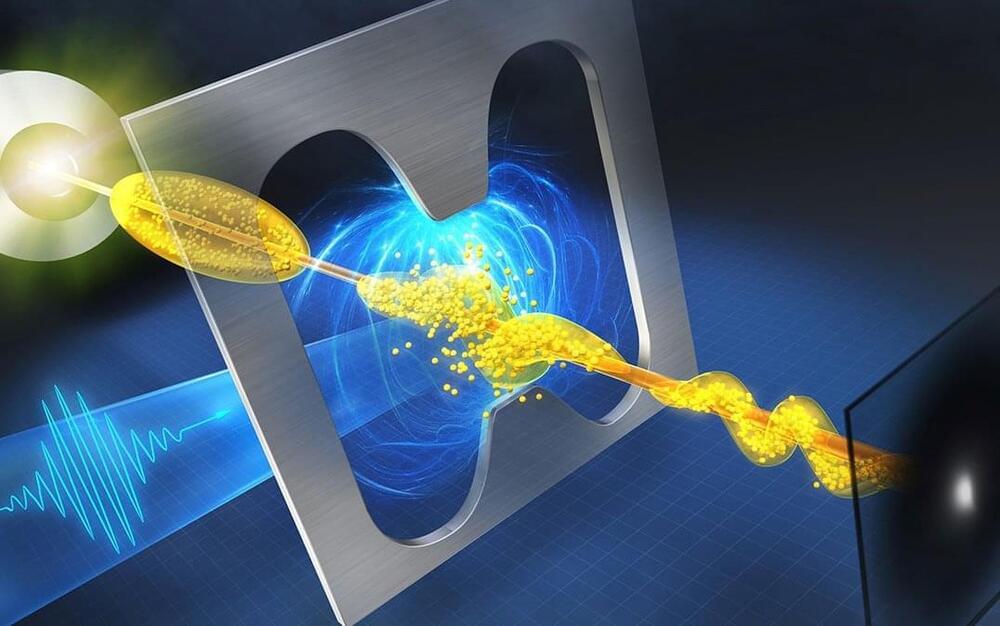

Researchers from the University of Tsukuba have shown how adding a tiny resonator structure to an ultrafast electron pulse detector reduced the intensity of terahertz radiation required to characterize the pulse duration (ACS Photonics, “Streaking of a Picosecond Electron Pulse with a Weak Terahertz Pulse”).

To study proteins—for example, when determining the mechanisms of their biological actions—researchers need to understand the motion of individual atoms within a sample. This is difficult not just because atoms are so tiny, but also because such rearrangements usually occur in picoseconds—that is, trillionths of a second.

One method to examine these systems is to excite them with an ultrafast blast of laser light, and then immediately probe them with a very short electron pulse. Based on the way the electrons scatter off the sample as a function of the delay time between the laser and electron pulses, researchers can obtain a great deal of information about the atomic dynamics. However, characterizing the initial electron pulse is difficult and requires complex setups or high-powered THz radiation.