Reichman University’s new Innovation Institute, which is set to formally open this spring under the auspices of the new Graziella Drahi Innovation Building, aims to encourage interdisciplinary, innovative and applied research as a cooperation between the different academic schools. The establishment of the Innovation Institute comes along with a new vision for the University, which puts the emphasis on the fields of synthetic biology, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Advanced Reality (XR). Prof. Noam Lemelshtrich Latar, the Head of the Institute, identifies these as fields of the future, and the new Innovation Institute will focus on interdisciplinary applied research and the ramifications of these fields on the subjects that are researched and taught at the schools, for example, how law and ethics influence new medical practices and scientific research.

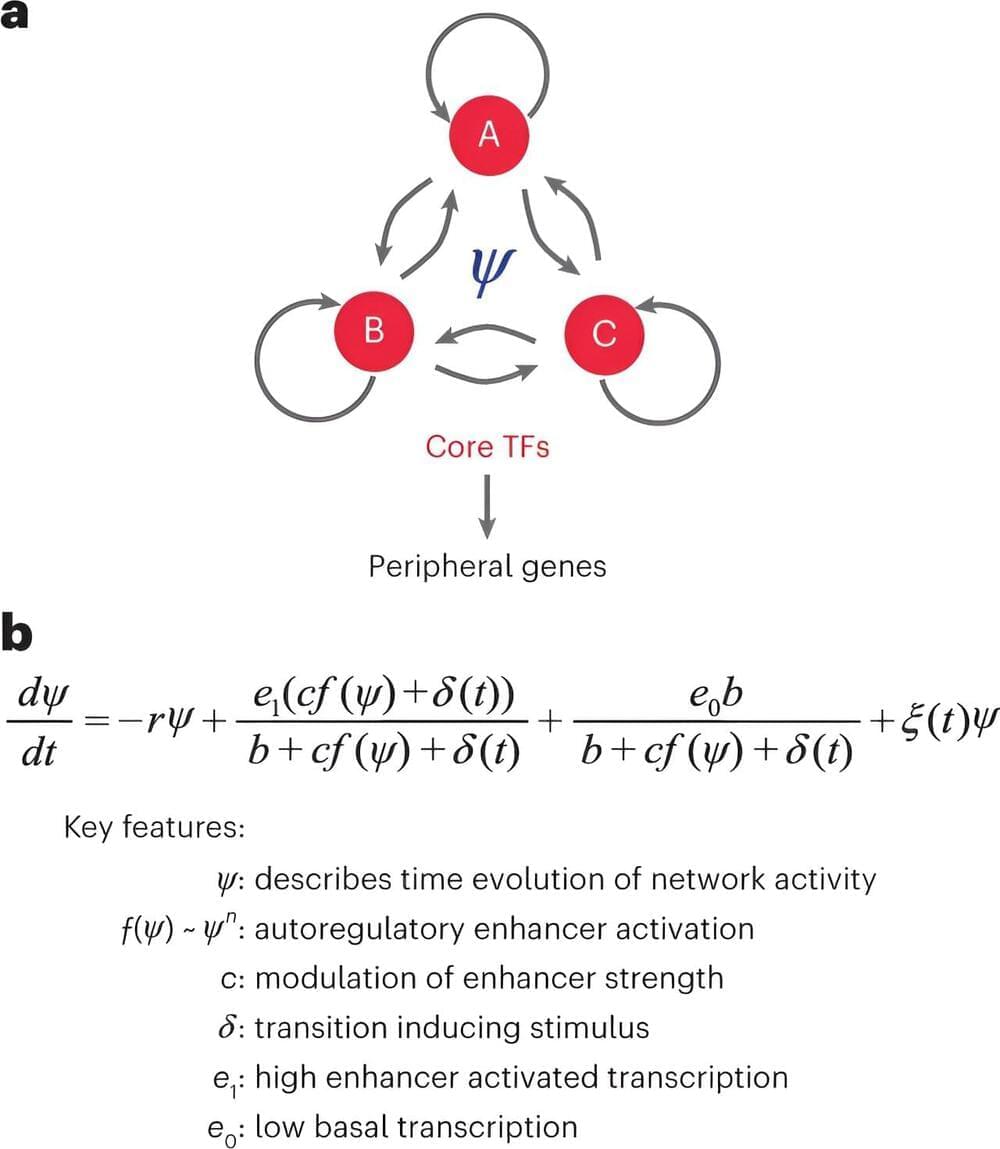

Synthetic biology is a new interdisciplinary field that integrates biology, chemistry, computer science, electrical and genetic engineering, enabling fast manipulation of biological systems to achieve a desired product.

Prof. Lemelshtrich Latar, with Dr. Jonathan Giron, who was the Institute’s Chief Operating Officer, has made a significant revolution at the University, when they raised a meaningful donation to establish the Scojen Institute for Synthetic Biology. The vision of the Scojen Institute is to conduct applied scientific research by employing top global scientists at Reichman University to become the leading synthetic biology research Institute in Israel. The donation will allow recruiting four world-leading scientists in various scopes of synthetic biology in life sciences. The first scientist and Head of the Scojen Institute has already been recruited – Prof. Yosi Shacham Diamand, a leading global scientist in bio-sensors and the integration of electronics and biology. The Scojen Institute labs will be located in the Graziella Drahi Innovation Building and will be one part of the future Dina Recanati School of Medicine, set to open in the academic year 2024–2025.